Snake scale facts for kids

Snakes, like other reptiles, have skin covered in scales. These scales come in many shapes and sizes, forming what we call snakeskin. Scales are super important for snakes! They protect the snake's body, help it move around, and keep moisture inside so the snake doesn't dry out. Scales can also help a snake blend in with its surroundings (camouflage) and even help some snakes catch their food. The cool patterns and colors you see on a snake are actually in the skin underneath the scales. When a snake stretches, you might see bright skin hidden between the scales, which can surprise predators!

Over time, snake scales have changed to do other cool things. Some snakes have scales that look like 'eyelashes', and others have clear scales that cover their eyes. The most famous special scale is the rattle found on North American rattlesnakes.

Snakes regularly shed their old skin and grow new ones. This helps them get rid of old, worn-out skin and any tiny bugs (parasites) that might be on them. It's also thought to help the snake grow bigger. The way scales are arranged on a snake is often used by scientists to tell different snake species apart.

Snakes have been a big part of human culture and religion for a long time. Their amazing scale patterns might have even inspired early artists. Sadly, people used to kill many snakes to make things like purses and clothes from their skin. This led to calls for using fake snakeskin instead. You can also find snake scales as cool designs in stories, art, and movies!

Contents

What Scales Do for Snakes

Snake scales mainly help reduce friction when a snake moves. Friction is the biggest reason snakes lose energy when they slither.

The large, long scales on a snake's belly (called ventral scales) are especially smooth. Some snakes that live in trees can even use the edges of these belly scales to grip branches. Snake skin and scales are also great at keeping water inside the snake's body, which is important for staying hydrated. Snakes can also feel vibrations from both the air and the ground. They use a clever system, possibly involving their scales, to tell the difference between these vibrations.

How Scales Developed

Reptiles, including snakes, evolved from animals that lived in water and on land (amphibians). To survive better on land and not dry out, reptile skin became thick and tough. It developed many layers of fats that acted like a waterproof shield and protected them from the sun's harmful rays. Over time, reptile skin cells became very hard and dry, made of a tough material called keratin. The outer and inner layers of all reptile scales are connected, which is why a snake sheds its entire skin in one piece.

What Scales Look Like Up Close

Snake scales are actually part of the snake's outer skin layer, called the epidermis. Each scale has an outer part and an inner part. The skin from the inner part folds back, creating a free area that overlaps the scale below it. A snake is born with a set number of scales. This number doesn't change as the snake grows older. However, the scales themselves get bigger and can change shape each time the snake sheds its skin (a process called moult).

Snakes have smaller scales around their mouth and on the sides of their body. These smaller scales allow the snake to stretch its mouth wide open so it can eat prey much bigger than itself! Snake scales are made of keratin, which is the same material that makes up your hair and fingernails. If you were to touch them, they would feel cool and dry.

Scale Surface and Shape

Snake scales come in many different shapes and sizes. Some scales are bumpy (granular), some are smooth, and others have a ridge or "keel" running down the middle. Often, snake scales have tiny pits, bumps, or other small features that you might see with your eyes or under a microscope. Scales can even be shaped into fringes, like on the Eyelash Bush Viper (Atheris ceratophora), or form rattles, like on rattlesnakes in North America.

Some older types of snakes, like boas and pythons, and even some advanced snakes like vipers, have small scales arranged randomly on their heads. Other more modern snakes have special, large, and symmetrical scales on their heads called shields or plates.

Snake scales can be round, like on Typhlopidae snakes. They can be long and pointy, like on the Green Vine Snake (Ahaetulla nasuta). They can be wide and leaf-like, as seen on green pit vipers (Trimeresurus species), or as wide as they are long, like on the Rat snake (Ptyas mucosus). Sometimes, scales can be keeled (have a ridge) either lightly or strongly, like on the Buff-striped keelback (Amphiesma stolatum). Some snakes, like certain Natrix species, have scales with two tips. Other snakes, like the Short Seasnake (Lapemis curtus), might have spiky scales that fit closely together. The Javan Mudsnake (Xenodermis javanicus) has large, non-overlapping bumps.

Another special type of snake scale is the brille or spectacle. This is a clear scale that covers the snake's eye, acting like a fused eyelid. It gets shed along with the rest of the old skin during moulting.

Rattles

The most unique change to a snake scale is the rattle found on rattlesnakes. The rattle is made of several loose, interlocking parts. When the snake shakes its tail, these parts rub against each other, making the warning sound. Only the very bottom part of the rattle is firmly attached to the tail.

When a rattlesnake is born, it only has a small "button" at the end of its tail. The first part of the rattle is added when the baby snake sheds its skin for the first time. A new section is added each time the snake sheds its skin, until a full rattle is formed. The rattle grows as the snake gets older, but parts can also break off. So, you can't always tell a rattlesnake's age just by the length of its rattle.

Scale Color

Most scales are made of a clear material called beta keratins. The colors you see on a snake's scales come from pigments (natural colors) in the deeper layers of its skin, not from the scale material itself. Scales can be almost any color this way, except for blue and green. Blue is created by the tiny structure of the scales, which scatters light to make a blue color. When this blue combines with yellow from the inner skin, it creates a beautiful, shimmering green!

Some snakes can slowly change the color of their scales. This often happens when a snake becomes lighter or darker depending on the season. In some cases, this color change can even happen between day and night.

Shedding Skin (Ecdysis)

The process of a snake shedding its scales is called ecdysis, or more commonly, moulting or sloughing. When a snake sheds, its entire outer layer of skin comes off in one piece. Snake scales are not separate pieces; they are extensions of the skin. So, they don't fall off one by one. Instead, the whole outer layer of skin peels off, like turning a sock inside out.

Shedding skin helps snakes in a few ways. First, it replaces old, worn-out skin. Second, it helps them get rid of tiny bugs like mites and ticks. Some people think shedding also helps snakes grow, but this idea is still debated for snakes.

Snakes shed their skin regularly throughout their lives. Before a snake sheds, it usually stops eating and finds a safe place to hide. Just before shedding, its skin looks dull and dry, and its eyes become cloudy or blue. The old outer skin then separates from the new skin underneath. After a few days, the eyes clear up, and the snake "crawls" out of its old skin. The old skin usually breaks near the mouth, and the snake wiggles out by rubbing against rough surfaces. Often, the shed skin peels backward from head to tail, like an old sock. Underneath, a new, larger, and brighter layer of skin has formed.

An older snake might shed its skin only once or twice a year. But a younger, still-growing snake might shed up to four times a year! The discarded skin is a perfect copy of the snake's scale pattern. If the shed skin is mostly complete, scientists can often use it to identify the snake species.

How Scales are Arranged

The way scales are arranged is important for identifying snake species. It's also useful for studying snake populations and helping to protect them. Except for the head, snake scales overlap like tiles on a roof. Snakes have rows of scales along most or all of their body. They also have many other special scales, either single or in pairs, on their head and other body parts.

The scales on a snake's back (dorsal scales) are arranged in rows along the length of their bodies. Each row is slightly offset from the one next to it. Most snakes have an odd number of scale rows across their body, though some species have an even number. For some water snakes, the scales are bumpy, and you can't easily count the rows.

The number of scale rows can vary a lot between species. For example, the Tiger Ratsnake has ten rows, while some pythons can have 65 to 75 rows! Most snakes in the largest snake family, the Colubridae, have 15, 17, or 19 rows of scales. The most rows are usually found in the middle of the snake's body, and the number decreases towards the head and tail.

Naming Snake Scales

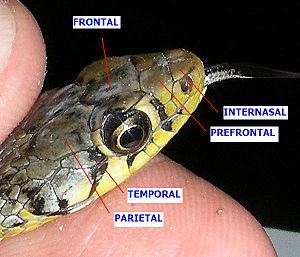

Scientists have special names for the different scales on a snake's head and body. Let's look at some of them, using the Buff-striped Keelback (Amphiesma stolata) as an example.

Head Scales

It's easiest to start identifying head scales by finding the nostril. The two scales around the nostril are called the nasals. In many snakes, the nostril is between these two scales. The outer nasal scale (closer to the snout) is the prenasal, and the inner one (closer to the eye) is the postnasal. Along the top of the snout, connecting the nasals on both sides, are scales called internasals. At the very tip of the snout, between the two prenasals, is the rostral scale.

The scales around the eye are called circumorbital scales. The clear scale covering the eye itself is called the spectacle, brille, or eyecap. The circumorbital scales towards the front (snout) are preocular scales, those towards the back are postocular scales, and those above the eye are supraocular scales. If there are scales below the eye, they are subocular scales. Between the preocular and postnasal scales are one or two scales called loreal scales. Some snakes, like elapids, don't have loreal scales.

The scales along the snake's lips are called labials. Those on the upper lip are supralabials or upper labials, and those on the lower lip are infralabials or lower labials. On top of the head, between the eyes and next to the supraoculars, is the frontal scale. The prefrontal scales are in front of the frontal scale, touching the internasals. The back of the top of the head has scales connected to the frontal scale called the parietal scales. On the sides of the back of the head, between the parietals above and the supralabials below, are scales called temporal scales.

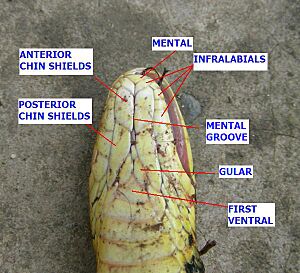

On the underside of the head, a snake has a front scale called the mental scale. Connected to the mental scale and along the lower lips are the infralabials or lower labials. Along the chin, connected to the infralabials, are two pairs of shields: the anterior chin shields (front pair) and the posterior chin shields (back pair).

Scales in the central throat area, which touch the first belly scales and are next to the chin shields, are called gular scales. The mental groove is a line running down the underside of the head, between the large chin shields and continuing between the smaller gular scales.

Body Scales

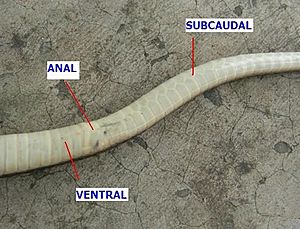

The scales on the main body of the snake are called dorsal or costal scales. Sometimes, there's a special row of larger scales along the very top of the snake's back, called the vertebral scales. The large scales on the snake's belly are called ventral scales or gastrosteges. The number of ventral scales can help identify the snake species. In more advanced snakes, the wide belly scales and rows of back scales match up with the snake's backbone, allowing scientists to count the vertebrae without having to cut the snake open.

Tail Scales

At the end of the snake's belly scales is a special scale called the anal plate. This plate protects the opening where waste and reproductive materials leave the snake's body. The anal scale can be a single scale or divided into two. The part of the body beyond the anal scale is considered the tail.

Sometimes, snakes have enlarged scales, either single or in pairs, under their tail. These are called subcaudals or urosteges. These subcaudals can be smooth or have a keel (ridge). The end of the tail can simply taper to a point (like most snakes), form a spine, end in a bony spur, a rattle (like on Crotalus), or a rudder (like on many sea snakes).

Why Scale Patterns are Important

Scales are not usually used to tell the difference between snake families, but they are very important for telling apart different genera (groups of species) and specific species. There's a detailed system for naming scales. The patterns, texture, colors, and whether the anal plate is single or divided, along with other body features, are the main ways scientists classify snakes down to their exact species.

In some areas, like parts of North America where there aren't too many different snake species, simple guides based on scale identification have been made for the public to tell venomous snakes from non-venomous ones. However, in places with many different snake species, like Myanmar, experts warn that it's very hard to tell venomous and non-venomous snakes apart without a careful examination.

The patterns of scales can also be used to identify individual snakes in field studies. Scientists sometimes clip specific scales, like the subcaudals, to mark individual snakes. This helps them estimate snake populations using methods like mark and recapture.

Telling Venomous from Non-Venomous Snakes

There is no easy way to tell if a snake is venomous or not just by looking at its scales. The correct way to find out if a snake is venomous is to identify its species with the help of experts. If an expert isn't available, you need to carefully examine the snake and use reliable books or websites about snakes in your specific area to identify it. Scale patterns help show the species, and then you can check if that species is known to be venomous.

Identifying snake species using scales requires a good amount of knowledge about snakes, how they are classified, the names of their scales, and access to scientific information. You cannot tell if a snake is venomous or not just by looking at scale diagrams if the snake is not caught. It is not safe to try and catch a snake just to check if it's venomous using scale diagrams. Most books or websites offer other ways to tell if a snake in the wild is venomous, besides just looking at its scales.

In some regions, having or not having certain scales might be a quick way to tell non-venomous and venomous snakes apart, but you must be careful and know about exceptions. For example, in Myanmar, if a snake doesn't have a loreal scale (a scale between the nasal scale and the pre-ocular scale), it might be a deadly Elapid. However, this rule doesn't work for vipers, which have many small scales on their heads. You also need to be careful to exclude known venomous snakes from the Colubrid family, like Rhabdophis.

In South Asia, if a snake has bitten someone and has been killed, it's advised to take the snake to the hospital. Medical staff might be able to identify it using scale diagrams, which can help them decide if and which anti-venom is needed. However, it's important to remember that trying to catch or kill a venomous snake is not advised, as the snake might bite more people.

Images for kids

-

Scales of a black-tailed rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus).

See also

In Spanish: Escamas de las serpientes para niños

In Spanish: Escamas de las serpientes para niños