Sothic cycle facts for kids

The Sothic cycle is a special period of time that ancient Egyptians used to keep track of their calendar. It lasts for 1,461 Egyptian years (which have 365 days each) or 1,460 Julian years (which average 365 and a quarter days).

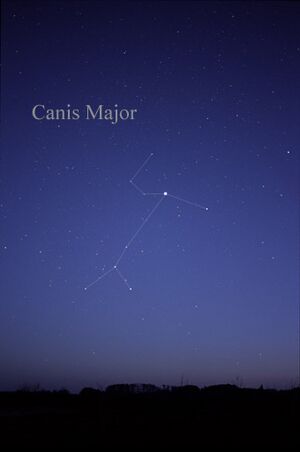

During a Sothic cycle, the 365-day Egyptian year slowly drifts. After 1,461 years, the start of their year lines up again with the first appearance of the star Sirius in the morning sky. This event is called the heliacal rising of Sirius. Sirius was very important to the Egyptians, who called it Sopdet.

Understanding the Sothic cycle helps experts learn more about the Egyptian calendar and its long history. Records of how the calendar moved out of sync with Sirius might have even helped create more accurate calendars later on, like the Julian calendar.

How the Cycle Works

The ancient Egyptian civil year had exactly 365 days. It did not have leap years until much later, around 22 BCE. This meant that their calendar months slowly moved out of sync with the actual solar year (the time it takes for Earth to orbit the Sun).

Imagine a clock that loses a little bit of time every day. Over a year, it would be off by a certain amount. The Egyptian calendar was like that. It lost about one day every four years compared to the solar year. This drift also matched how it moved out of sync with the Sothic year.

The Sothic year is the time it takes for Sirius to appear in the same spot in the sky each year. It's almost exactly 365.25 days long. Because the Egyptian calendar was exactly 365 days, it fell behind Sirius by about one day every four years.

This steady drift meant that after 1,461 Egyptian civil years (or 1,460 Julian years), the calendar would "catch up" and the New Year would once again line up with the heliacal rising of Sirius.

How We Found Out About It

People in ancient times already knew about this calendar cycle. A writer named Censorinus described it in his book in 238 CE. He said the cycle had reset 100 years earlier, on August 12.

In the 19th century, an early expert on Egypt, Isaac Cullimore, studied the cycle. He suggested that Censorinus's date might be a bit off and that the reset was more likely in 136 CE. He also thought the cycle was first used around 1600 BCE.

Later, in 1904, a scholar named Eduard Meyer carefully looked through old Egyptian writings. He searched for any mentions of when Sirius appeared at dawn on specific calendar dates. He found six such mentions. These findings became important for figuring out the timeline of ancient Egyptian history.

One record mentioned the heliacal rising of Sirius happening on the Egyptian New Year's Day between 139 CE and 142 CE. Astronomical calculations show that Sirius actually rose on July 20, 139 CE (Julian calendar).

By comparing the Egyptian calendar date of Sirius's rising with the Julian calendar date, Meyer could figure out how many days the Egyptian calendar had drifted. This helped him calculate how many years had passed since the beginning of a Sothic cycle.

To make these calculations accurate, it's important to know where the observation was made. The latitude (how far north or south a place is) changes when Sirius can be seen rising. Official observations were known to happen in places like Heliopolis (near Cairo), Thebes, and Elephantine (near Aswan). For example, Sirius was seen rising in Cairo about 8 days after it was seen in Aswan.

Meyer first thought the Egyptian civil calendar was created in 4241 BCE. However, more recent studies have questioned this. Many experts now believe the observation Meyer used might refer to a different cycle, around 2781 BCE, or they don't think the document he used actually refers to Sirius's rising at all.

Why It's Tricky to Use

Using the Sothic cycle to date ancient events can be difficult for a few reasons:

- Location Matters: Knowing the exact place where Sirius was observed is crucial. A small mistake in location can throw off the dates by many decades.

- Imprecise Observations: Because the Egyptian calendar lost one day every four years, Sirius's heliacal rising would happen on the same calendar day for four years in a row. This means an observation could be from any of those four years, making it less precise.

There are also some bigger challenges with using the Sothic cycle for dating:

- Missing Pharaohs: The ancient records of Sirius observations don't usually mention which pharaoh was ruling at the time. Experts have to guess this information.

- Calendar Changes: We assume the Egyptian civil calendar stayed the same for thousands of years. But if the Egyptians changed their calendar even once, it could make these calculations less reliable.

- No Direct Mention: Ancient Egyptian writings don't directly talk about the Sothic cycle. This might be because it was so obvious to them, or because relevant texts have been lost over time.

Because of these challenges, some historians today believe it's hard to give exact dates for events earlier than the 8th century BCE using the Sothic cycle.

For example, some people have tried to link the Theran eruption (a huge volcanic explosion) to the start of the Eighteenth Dynasty. This is because volcanic ash was found in Egyptian ruins. Since scientists think the eruption happened around 1626 BCE, this would mean Sothic cycle dating might be off by 50-80 years for that period. However, these claims are still debated by historians.

See also

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |