Minoan eruption facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Minoan eruption of Thera |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Volcano | Thera |

| Date | c. 1600 BCE (see below) |

| Type | Ultra Plinian |

| Location | Santorini, Cyclades, Aegean Sea 36°24′36″N 25°24′00″E / 36.41000°N 25.40000°E |

| VEI | 6 |

| Impact | Devastated the Minoan settlements of Akrotiri, the island of Thera, communities and agricultural areas on nearby islands, and the coast of Crete with related earthquakes and tsunamis. |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 396: Seconds were provided for longitude without minutes also being provided. | |

The Minoan eruption was a huge volcanic eruption that caused a lot of damage. It happened on the Aegean island of Thera, also known as Santorini, around 1600 BCE. This powerful eruption destroyed the Minoan city of Akrotiri. It also harmed towns and farms on nearby islands and the coast of Crete. This was due to strong earthquakes and giant tsunami waves that followed.

The eruption was incredibly powerful, with a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) between 6 and 7. It shot out about 28 to 41 cubic kilometers (17 to 25 cubic miles) of rock and ash. This makes it one of the biggest volcanic events in human history. The ash from the Minoan eruption is found at many archaeological sites in the Eastern Mediterranean. Because of this, finding its exact date is very important. Scientists and archaeologists have debated the date for many years.

Even though there are no clear ancient writings about the eruption, some old texts might describe it. The Egyptian Tempest Stele might talk about its huge ash cloud and volcanic lightning. Also, the Chinese Bamboo Annals mentioned strange yellow skies and summer frost. This happened at the start of the Shang dynasty. These events might have been caused by a volcanic winter, like the "Year Without a Summer" in 1816 after the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora.

Contents

The Eruption of Thera

How the Volcano Works

The Thera volcano has erupted many times over hundreds of thousands of years. This happened before the Minoan eruption. Each time, the volcano would erupt violently. Then, it would collapse into a round, sea-filled caldera. Many small islands would form a circle around this caldera. Over time, the caldera would slowly fill with magma. This would build a new volcano, which would erupt and collapse again. This process kept repeating.

Right before the Minoan eruption, the caldera walls formed a ring of islands. The only way in was between Thera and the tiny island of Aspronisi. This huge eruption happened on a small island. It was just north of Nea Kameni, which is in the center of the old caldera. The northern part of the caldera filled with volcanic ash and lava. Then, it collapsed again.

How Big Was the Eruption?

It has been hard to figure out how big the eruption was. Most of the material landed in the sea. This makes it tough to measure the amount of rock and ash that came out. Scientists have estimated the volume of the Minoan eruption to be between 13 and 86 cubic kilometers (8 to 53 cubic miles).

New studies from 2015 to 2019 looked at sea sediments and seismic data. They estimate the volcano shot out about 28 to 41 cubic kilometers (17 to 25 cubic miles) of material.

The study showed that the first big eruption was the largest part. It blasted out 14 to 21 cubic kilometers (8.7 to 13 cubic miles) of magma. This was half of all the material erupted. This eruption is similar to other huge eruptions in history. These include the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora and the 1257 Samalas eruption.

What Happened During the Eruption?

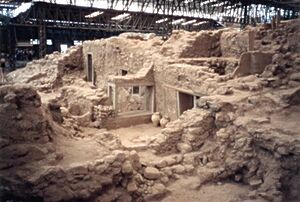

On Santorini, there is a 60-meter (200-foot) thick layer of white tephra. This layer clearly shows the ground level before the eruption. It has three different bands, showing different parts of the eruption. Scientists have found four main eruption phases and one small warning phase. The first ash layer was thin. It also showed no signs of being washed away by winter rains. This means the volcano gave people a few months' warning. No human remains have been found at Akrotiri. This suggests people probably left the island because of the early volcanic activity. It is also thought that earthquakes hit Santorini months before the eruption, damaging towns.

The first major phase (Minoan A) was very active. It covered the area with up to 7 meters (23 feet) of pumice and ash. This mostly went to the southeast and east. Buildings were buried but not badly damaged. The second (Minoan B) and third (Minoan C) phases involved fast-moving clouds of hot gas and ash called pyroclastic surges. There were also lava fountains. These phases might have caused tsunamis. Buildings not buried in the first phase were completely destroyed. The third phase also started the caldera's collapse. The fourth and final major phase (Minoan D) had different activities. These included rock-filled ash deposits, lava flows, mudslides (called lahars), and ash falling from the sky. This phase finished the caldera's collapse. This created giant tsunami waves, known as megatsunamis.

How the Island Changed

The island's shape changed a lot after the eruption. The caldera had formed just before the eruption. The island became smaller, and the southern and eastern coastlines moved back. During the eruption, the land was covered by pumice. In some places, the coastline disappeared under thick tuff deposits. In other areas, new coastlines stretched out into the sea. After the eruption, the island's shape kept changing. Wind and rain slowly removed the pumice from higher areas to lower ones.

Volcano Science

The eruption was an "Ultra Plinian" type. This means it was extremely powerful. It created an eruption column that reached about 30 to 35 kilometers (19 to 22 miles) high. This column went all the way into the stratosphere. Also, the magma under the volcano touched the shallow sea. This caused very strong explosions called phreatomagmatic blasts.

The eruption also caused huge tsunami waves, 35 to 150 meters (115 to 492 feet) high. These waves destroyed the northern coast of Crete, which is 110 kilometers (68 miles) away. Coastal towns like Amnisos were hit. Building walls were knocked out of place. On the island of Anafi, 27 kilometers (17 miles) to the east, ash layers 3 meters (10 feet) deep have been found. Pumice layers were also found on slopes 250 meters (820 feet) above sea level.

Pumice from the Thera eruption has been found in other parts of the Mediterranean. Ash layers in cores from the seabed and lakes in Turkey show that most ash fell to the east and northeast of Santorini. Ash found on Crete was from an early part of the eruption. This happened weeks or months before the main eruption. It probably did not cause much damage to Crete.

When Did the Eruption Happen?

The Minoan eruption is a very important event for dating the Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. It gives a fixed point to help line up all the dates from the second millennium BCE in the Aegean Sea. This is because signs of the eruption are found everywhere in the region. However, there is a big debate about its exact date. Dates found by studying ancient objects (archaeology) are about 100 years younger than dates found by radiocarbon dating. This difference has caused a big argument among scientists.

Archaeological Dating

Archaeologists have created timelines for ancient cultures in the eastern Mediterranean. They do this by looking at the design styles of objects found in different layers of the ground. If they can date the objects, they can date the layer they came from. This is called sequence dating. In the Aegean, people traded many objects. This helps compare their timeline with the very accurate timeline of ancient Egypt. This allows archaeologists to find exact dates for events in the Aegean.

The Minoan eruption happened at the end of the Late Minoan IA (LM-IA) period in Crete. It was also at the end of the Late Helladic I (LH-I) period on the mainland. The debate is about which Egyptian period happened at the same time as LM-IA. For decades, archaeologists believed LM-IA was at the same time as Dynasty XVIII in Egypt. They thought the end of LM-IA was at the start of Thutmose III's rule.

Objects found in tombs from the LH-I period are from the New Kingdom. Workshops on Santorini that used pumice from the eruption are only found in New Kingdom layers. A milk bowl found on Santorini, used before the eruption, has a New Kingdom pottery style. An Egyptian writing on the Ahmose Tempest Stele describes a huge disaster. This disaster sounds like the Minoan eruption. All this evidence suggests the eruption happened after Ahmose I became pharaoh. This would place the eruption between about 1550 and 1480 BCE.

Some scientists who think the eruption happened earlier say that comparing pottery between the Aegean and Egypt is not always exact. They suggest other ways to look at LM-IA pottery. This could mean LM-IA started much earlier. They also say that the pumice workshops and the Tempest Stele only show the earliest possible date for the eruption.

Radiocarbon Dating

Raw radiocarbon dates are not exact calendar years. This is because the amount of radiocarbon in the air changes over time. These raw dates are turned into calendar dates using calibration curves. These curves are updated regularly by scientists. The accuracy of the calendar dates depends on how well the curve shows past radiocarbon levels. The newest curve is called IntCal20.

In the 1970s, early radiocarbon dates showed a big difference from archaeological dates. Archaeologists first thought these dates were wrong. But over the years, with better methods, the range of possible eruption dates became much smaller. Radiocarbon dating now strongly suggests the eruption happened in the late 17th century BCE.

In 2018, scientists found a small error in earlier calibration curves. This error was for the period between 1660 and 1540 BCE. The new calibration curve allowed older radiocarbon dates to fit more with the 16th century BCE. This helped to reduce the disagreement with archaeological evidence. This error was confirmed and added to the IntCal20 curve.

In 2020, some thought there might be a special error in calibration curves for the Mediterranean area. If this is true, then the eruption date would go back to the 17th century BCE. However, others say that the IntCal20 curve already includes these small differences.

Even though the new IntCal20 curve does not rule out a 17th-century BCE date, it makes it more likely that the eruption happened in the 16th century BCE. This helps to solve the long-standing date problem. However, the exact year of the eruption is still not settled.

Ice Cores and Tree Rings

A huge eruption like Thera's should leave traces in nature. These include ice cores and tree rings. The Thera eruption could have released a lot of sulfur. A very large amount could cause big climate changes. These changes would show up in ice cores and tree rings. Tree ring dating is very precise. It can date events to the exact year. It can also show local climate changes.

In 1987, a large amount of sulfate was found in Greenland ice cores. It was dated to 1644 ± 20 BCE. Some thought this was from the Minoan eruption. In 1988, a big climate change and extreme cold were found in tree rings. This was dated to 1627 BCE. This was also thought to be linked to the Minoan eruption.

But archaeologists who preferred a later eruption date were not convinced. They said there was no proof that these events were caused by the Minoan eruption.

Since 2003, studies of volcanic ash in the 1644 ± 20 BCE sulfate layer did not match Santorini's ash. Instead, they matched ash from another big eruption, Mount Aniakchak. This ruled out the Minoan eruption as the cause. In 2019, the Greenland ice-core timeline was updated. The Aniakchak eruption date moved to 1628 BCE. This explained the 1627 BCE cold period without needing Thera. Also, radiocarbon dating with the newest IntCal20 curve no longer supports a 1627 BCE eruption date for Thera.

Because of the newer radiocarbon dates and updated ice core timelines, scientists have looked for other possible signs. These signs in ice cores and tree rings from the 17th and 16th centuries BCE might be from the Minoan eruption. However, the eruption might not have been strong enough to leave a clear sign in these records.

What Was the Impact?

Akrotiri City

The eruption completely destroyed the city of Akrotiri on Santorini. The city was buried under layers of pumice and ash. Evidence shows that some people who survived came back. They tried to get their belongings and perhaps bury those who died.

Minoan Crete

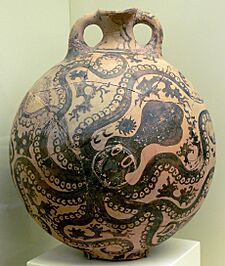

The eruption was also felt on Minoan Crete. In northeastern Crete, earthquakes destroyed places like Petras. Giant 9-meter (30-foot) high tsunami waves crashed over coastal towns such as Palaikastro. Ash and pumice fell across the island. Sometimes, people collected and stored it.

After the eruption, the Minoans recovered quickly. The time after the eruption is even seen as the best period of Minoan culture. Many damaged places were rebuilt. This included Petras and Palaikastro. At Palaikastro, new buildings were made with high-quality stone. New Minoan palaces were built at Zakros and Phaistos. However, some other places, like Galatas and Kommos, became less important.

The long-term effects of the eruption are still debated. Right after the eruption, some strange cultural changes happened. For example, some special pools called lustral basins were filled in. Some historians think that even though the culture seemed rich, there were hidden economic and political problems. These problems might have led to the fall of the Minoan society later. But other evidence suggests this was not true for the whole island.

Chinese Records

Some researchers believe a volcanic winter from an eruption in the late 17th century BCE matches old Chinese records. These records talk about the fall of the Xia dynasty in China. The Bamboo Annals say that the fall of the Xia dynasty and the rise of the Shang dynasty (around 1618 BCE) came with "yellow fog, a dim sun, then three suns, frost in July, famine, and the withering of all five cereals".

Effect on Egyptian History

Heavy rainstorms, which damaged much of Egypt, are described on the Tempest Stele of Ahmose I. Some think these storms were caused by short-term climate changes from the Thera eruption. The exact dates of Ahmose I's rule are debated. Proposed reigns range from 1570 to 1546 BCE or 1539 to 1514 BCE. Radiocarbon dating of his mummy suggests a date around 1557 BCE. This would only overlap with the later estimates of the eruption date.

If the eruption happened during Egypt's Second Intermediate Period, there might be no Egyptian records of it. This period was a time of general disorder in Egypt.

Some say the damage from these storms might have been caused by an earthquake after the Thera eruption. Others suggest it was from a war with the Hyksos. They think the storm description is just a way to talk about chaos that the Pharaoh was trying to control. Other ancient Egyptian writings, like Hatshepsut's Speos Artemidos, also describe storms. But these are clearly symbolic, not real events.

Greek Stories

The Titanomachy

The eruption of Thera and its ash might have inspired the myths of the Titanomachy in Hesiod's Theogony. This story tells of a great battle between the gods and the Titans. The story might have picked up ideas from old folk tales in western Anatolia. Hesiod's descriptions have been compared to volcanic activity. For example, Zeus's thunderbolts could be volcanic lightning. The boiling earth and sea might be a sign of the magma chamber breaking open. The huge flames and heat could be evidence of explosions from steam.

Atlantis

Spyridon Marinatos, who found the Akrotiri archaeological site, thought the Minoan eruption was the basis for Plato's story of Atlantis. This idea is still popular today, appearing in TV shows like BBC's Atlantis. However, most experts today do not support this view.

|

See also

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |