Soweto Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Soweto Uprising |

|

|---|---|

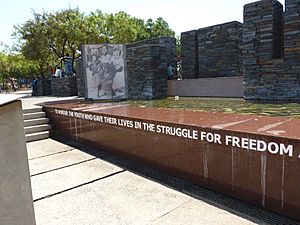

The Hector Pieterson Memorial, in Soweto. Hector Pieterson was a 12-year-old student, who was killed during the uprising.

|

|

| Location | Soweto, South Africa |

| Date | 16–18 June 1976 |

| Deaths | Minimum of 176 with some estimates ranging up to 700 |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

1,000+ |

| Victims | Students |

The Soweto Uprising was a series of protests by high school students in South Africa. It began on 16 June 1976. Students were protesting against a new rule that forced them to learn in Afrikaans. This language was linked to the unfair system of apartheid, which separated people by race.

About 20,000 students took part in these protests. The police reacted with great force. It is thought that at least 176 people died, but some estimates say up to 700. To remember these important events, 16 June is now a public holiday in South Africa called Youth Day.

Contents

Why Students Protested

Black South African high school students in Soweto were upset about a rule from 1974. This rule, called the Afrikaans Medium Decree, said that all black schools had to teach subjects in both Afrikaans and English. They had to use both languages equally.

Afrikaans was seen as the language of the apartheid government. Because of this, black South Africans preferred to learn in English. Even the special areas set up for black people, called Bantustans, chose English and a local African language as their official languages. English was also becoming more important in business and jobs.

The government wanted to make Afrikaans more common among black Africans. They used an old law from 1909 as an excuse. This law said that only English and Dutch (which later became Afrikaans) were official languages. White students, however, learned other subjects in their own home language.

New Language Rules

J.G. Erasmus, a director for black education, announced the new rules. From January 1, 1975, Afrikaans had to be used for math and social studies for students in 7th grade. English would be used for science and practical subjects like cooking or art. Local African languages could only be used for religious lessons, music, and physical education.

Black people were very angry about this rule. Desmond Tutu, a famous bishop, said Afrikaans was "the language of the oppressor." Teacher groups also spoke out against the decree.

Punt Janson, a government minister, said he would not ask black people what they thought. He believed black people should be trained for farm or factory work. He said they might work for someone who spoke English or Afrikaans. He didn't see why there should be arguments about the language of teaching.

Learning Challenges

Changing the language of teaching made it harder for students to learn. They had to focus on understanding the language itself, not just the subject. This made it difficult to think deeply about what they were learning.

The anger grew. On April 30, 1976, students at Orlando West Junior School in Soweto went on strike. They refused to go to school. Their protest quickly spread to many other schools in Soweto.

Students felt they deserved the same education as white South Africans. Also, very few people in Soweto actually spoke Afrikaans. A student named Teboho MacDonald Mashinini suggested a meeting. On June 13, 1976, students formed an Action Committee. This group later became the Soweto Students' Representative Council. They planned a large march for June 16 to make their voices heard.

The Uprising Begins

On the morning of June 16, 1976, between 10,000 and 20,000 black students gathered. They walked from their schools towards Orlando Stadium. Their goal was to protest against learning in Afrikaans. Many students joined the protest without knowing about it beforehand.

The Soweto Students' Representative Council (SSRC) Action Committee planned the march. They had support from the wider Black Consciousness Movement. Teachers in Soweto also supported the march. The Action Committee made sure the students would be well-behaved and peaceful.

Tsietsi Mashinini led students from Morris Isaacson High School. They met up with students from Naledi High School. As they marched, they found police blocking their way. The protest leader asked everyone not to make the police angry. The march then continued on a different path.

They eventually reached Orlando High School. A crowd of 3,000 to 10,000 students gathered. They sang songs and held signs. Some signs said, "Down with Afrikaans" and "If we must do Afrikaans, Vorster must do Zulu".

Police Reaction and Deaths

The police used a trained dog on the protesters. The students reacted by killing the dog. Then, the police started shooting directly at the students. The violence quickly got worse. On the first day, 23 people died in Soweto. One of them was Dr. Melville Edelstein, who had worked to help black communities.

Aftermath and Impact

The number of people who died is usually said to be 176, but some estimates go up to 700. The uprising happened when the South African government was trying to make apartheid look less harsh to the world. In October 1976, they declared Transkei "independent." This was meant to show they believed in self-rule. However, other countries saw Transkei as a puppet state, controlled by South Africa.

For the government, the uprising was the biggest challenge to apartheid yet. It caused economic and political problems. The international boycott against South Africa grew stronger. It would be 14 years before Nelson Mandela was freed from prison. But the government could never bring back the peace of the early 1970s. Black resistance continued to grow.

Many white South Africans were also upset by the government's actions. The day after the shootings, about 400 white students from the University of the Witwatersrand marched in Johannesburg to protest. Black workers also went on strike and joined the protests. Riots broke out in black townships in other South African cities too.

Most of the violence ended by late 1976. By then, over 600 people had died. The ongoing clashes in Soweto caused the economy to suffer. The South African currency, the South African rand, lost value quickly. The government faced a major crisis.

The African National Congress (ANC) printed leaflets with the slogan "Free Mandela, Hang Vorster." This linked the language issue to their fight for freedom. It helped the ANC become a leading group in the anti-apartheid movement.

Global Reactions

The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 392. This resolution strongly condemned the violence and the apartheid government.

A week after the uprising, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with South African President Vorster. They discussed the situation in Rhodesia, but the Soweto uprising was not a main topic. Kissinger and Vorster met again in September 1976. Students in Soweto protested Kissinger's visit and were again shot at by police.

ANC members living outside South Africa called for other countries to take action. They asked for more economic sanctions against South Africa.

Soweto Uprising in Media

Pictures of the riots spread around the world and shocked many people. The famous photograph of Hector Pieterson, taken by Sam Nzima, caused outrage. It brought international criticism against the apartheid government.

The Soweto riots have been shown in several films. These include Cry Freedom (1987) and Sarafina! (1992). The riots also inspired the novel A Dry White Season by André Brink and a movie of the same title (1989).

The uprising also appeared in the 2003 film Stander. The song "Soweto Blues" by Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba tells the story of the Soweto Uprising and the children's role in it.

Radio Documentaries

In June 1996, a radio project in Johannesburg created a documentary. It told the story of June 16, 1976, from the point of view of people who lived in Soweto at the time. Many students who planned or joined the uprising shared their experiences. Others, like photographer Peter Magubane and reporter Sophie Tema, also took part. A white doctor, Tim Wilson, who declared Hector Pieterson dead, was also interviewed.

This program was broadcast on South African radio stations. The next year, BBC Radio 4 and BBC World Service broadcast a new version. It included fresh interviews and was called The Day Apartheid Died. This program won several awards. In May 1999, BBC Radio 4 broadcast it again as The Death of Apartheid.

See also

In Spanish: Disturbios de Soweto para niños

In Spanish: Disturbios de Soweto para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |