St Paul's Cross facts for kids

Paul's Cross (sometimes called "Powles Crosse") was a special outdoor pulpit (a raised stand for a speaker) in St Paul's Churchyard. This was the area around Old St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. It was the most important public speaking spot in England during the Tudor and early Stuart periods. Many big announcements about changes in religion and government during the Reformation were made here.

The original pulpit stood in an open area called 'the Cross yard'. This was on the north-east side of St Paul's Churchyard. It was also near the buildings where London's book publishers and sellers worked.

Today, a tall stone column with a golden statue of Saint Paul stands in this area. This monument is also called "Paul's Cross," but it's not in the exact spot where the old pulpit was. A special stone marks the real place where the pulpit stood from 1449 until 1635. It was taken down during renovation work by Inigo Jones.

Contents

History of Paul's Cross

Early Beginnings (Before 1400s)

The eastern part of the churchyard was used by the city government long ago. It was a place for the London 'folkmoot', which was a big meeting for all the people.

The first known folkmoot here was in 1236. A king's judge, John Mansell, announced that King Henry III wanted London to be well-governed. In 1259, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King attended another meeting. Londoners had to promise loyalty to the King there. Later, people also gathered here to support Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, who was against the King.

In the 1400s, interesting events happened here. Around 1422, a chaplain named Richard Walker admitted to practicing magic. After promising to stop, his magic books were burned in public, and he was set free.

Later, bishops used the cross to speak about religious ideas. Reginald Pecock, a bishop, spoke against a group called Lollardy in 1447. But in 1457, he had to apologize publicly at the cross. He threw his own writings, which were seen as against church teachings, into a fire. About 20,000 people and the Archbishop of Canterbury watched this event.

In 1483, Jane Shore, who was a friend of King Edward IV, was brought to the cross. She was stripped of her fancy clothes and jewelry.

On June 22, 1483, a preacher named Ralph Shaa gave a sermon from Paul's Cross. He spoke about Richard, Duke of Gloucester's claim to be King of England. This speech was a key step in Richard III taking the throne from his young nephew, Edward V. Edward V was one of the Princes in the Tower.

Rebuilding in the 1400s

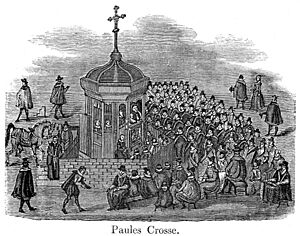

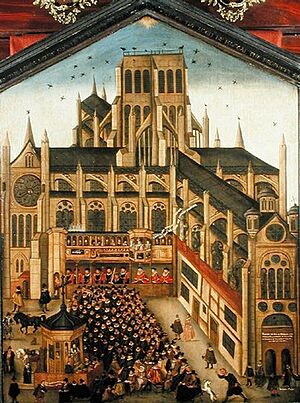

Bishop Thomas Kempe rebuilt the cross in 1449. It became a grand outdoor pulpit, mostly made of wood. It had space inside for three or four people. It stood on stone steps and had a lead-covered roof. There was also a walkway around it. This walkway was later enclosed with a low wall in the early 1600s. The whole pulpit building was shaped like an octagon and was about 37 feet wide.

Paul's Cross in the 1500s

For much of the 1500s and early 1600s, sermons were given here every week. The bishops of London chose the preachers. For important events, senior church leaders like deans and bishops would preach. On other Sundays, newer preachers from Oxford and Cambridge, or local London preachers, would fill the schedule.

Early in Queen Elizabeth I's reign, it was sometimes hard to find preachers. They needed to be willing to give a two-hour sermon at Paul's Cross. Later, with more money for the sermons, preaching 'at the cross' became a goal for young church leaders. Many of these sermons were printed so more people could read them. About 370 Paul's Cross sermons still exist today, with over 300 printed copies.

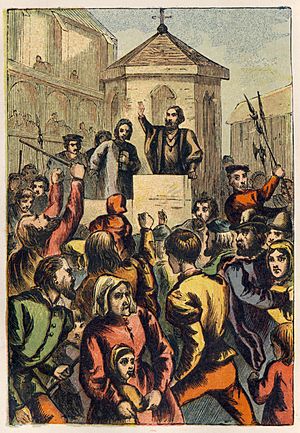

Paul's Cross was one of the few open spaces in the busy city. Important royal announcements were often made here. Because of this, it was the site of several public disturbances. A speech here led to the 1517 Evil May Day riots against foreigners.

After Catholic Queen Mary became queen, the first sermon given here caused a riot. A dagger was thrown at the speaker, Bishop Bourne, but it missed him. He had to be quickly taken to safety. Because of this, Mary's successor, Elizabeth I, kept the pulpit empty for a long time. She wanted to prevent more riots.

When Dr. Samson finally came to the Cross to announce Elizabeth's religious plans, the keys to the pulpit were missing. The Lord Mayor had to order the door to be forced open. In Elizabeth's early years, Paul's Cross was very important for sharing her religious policies with the public.

On June 15, 1559, John Jewel gave his famous 'Challenge' sermon here. He said he would become Catholic if his opponents could prove certain Catholic teachings from the first 600 years after Christ. This sermon led to many published books and arguments. There were also sermons against the Puritan Movement in 1572. Later, in 1589, Richard Bancroft attacked Puritan actions in a sermon.

During the Essex Rebellion, the Earl of Essex planned his arrival in London. He and his followers reached St Paul's just as the Paul's Cross sermon was ending. He hoped to get support from the city leaders.

Who Attended the Sermons?

People's diaries and other writings from the time show that Paul's Cross sermons were popular. This was especially true during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. However, their popularity went down in the 1630s. This was partly because they moved inside the cathedral choir after 1635.

An old French learning guide from 1573 describes visiting the Paul's Cross sermons. It says that members of the royal court and senior church leaders might be seen there. However, the Lord Mayor of London, city leaders, and their wives attended much more often than the nobility. Members of the city's trade guilds also attended. They often sat together formally for special events like the Accession Day sermon. Attending these sermons became an important way for the city government to mix their traditions with Protestant teachings after the Reformation.

The End of Paul's Cross

Some people believed the pulpit cross was destroyed in 1643. This was during the start of the First English Civil War, under an order to remove "idolatry monuments." However, old records show that the pulpit cross was already gone by 1641. It was most likely taken down in 1635. At that time, the area around the cathedral was being used for renovation work on the building.

The 20th Century Monument

Between 1908 and 1910, a new structure was built near the site of Paul's Cross. The money for this came from the will of a lawyer named Henry Charles Richards. Richards had hoped the old medieval preaching cross would be rebuilt. But the leaders of St Paul's Cathedral decided this would not fit with the cathedral's design. The cathedral had been rebuilt in the 1600s by Sir Christopher Wren.

The new monument was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield. It has a statue of Saint Paul by Sir Bertram Mackennal. The statue stands on a Doric column made of Portland stone. There was a small argument about how the cathedral used Richards's money. In 1972, the monument was officially recognized as a Grade II historic building.

See also

In Spanish: St Paul's Cross para niños

In Spanish: St Paul's Cross para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |