Stevens Pass Historic District facts for kids

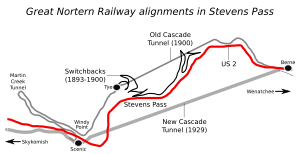

The Stevens Pass Historic District is a special area in the mountains of Washington state. It stretches about 3.2 miles (5.1 km) wide and 18.2 miles (29.3 km) long. This area includes the old railroad route through Stevens Pass. It goes from the Martin Creek Tunnel on the west side to the eastern entrance of the current Cascade Tunnel. The land here is very rugged, with lots of trees and rocky granite cliffs.

The Cascade Range mountains made it hard for the Great Northern Railway to reach the Puget Sound area. They needed a way to get their trains across these tall mountains. They found a good spot at Stevens Pass, which is about 4,000 feet (1,219 m) high. This pass is about 45 miles (72 km) east of Seattle. The railway first tried a clever system of zig-zag tracks. Later, they built a tunnel to replace these tracks. Then, they built an even newer, longer tunnel.

The Stevens Pass Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. This means it's an important historical site.

Contents

Crossing the Mountains: Switchbacks

In the early 1890s, engineers explored the area to find the best way for trains to cross Stevens Pass. They came up with a system called "switchbacks." Imagine a train going forward, then stopping, switching tracks, and going backward for a bit, then switching again to go forward. This is how switchbacks work, like a giant zig-zag path up a mountain.

The railway workers cut flat paths into the mountainside. They also built wooden bridges over small valleys. There were three switchbacks on the eastern side of the pass and five on the steeper western side. This system was very slow and took a lot of time. For example, it needed 13 miles (21 km) of track to cover a distance of only 3 miles (4.8 km) in a straight line.

Winter brought heavy snow and landslides, making the switchback route very difficult to use. By 1897, the railway knew they needed a better solution. So, they started building a long tunnel to go right through the mountain. This tunnel would bypass the slow and dangerous switchbacks.

The First Tunnel and Snow Sheds

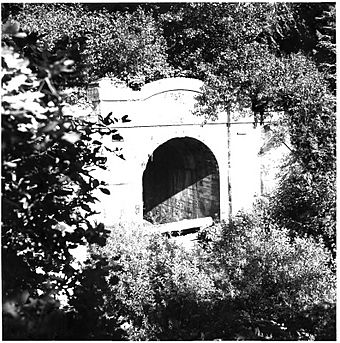

The first tunnel was finished in 1900. It was 13,283 feet (4,049 m) long, which is about 2.5 miles! The tunnel had a slight downhill slope towards the west. Both ends of the tunnel had concrete entrances with strong pillars. The entire inside of the tunnel was lined with concrete.

To protect the tracks from heavy snow and landslides, the railway built many "snow sheds." These were like long roofs over the tracks. They were designed to let snow and debris slide over the top of the railway, instead of blocking the trains. Before a big snowslide disaster in 1910, there were 17 snow sheds covering about 7,593 feet (2,314 m) of track. More sheds were added over time as needed.

One special snow shed was built in Wellington. It was 3,900 feet (1,189 m) long and was strong enough for two tracks. This was thought to be the first double-track snow shed ever built. Even with these improvements, heavy snow still caused problems.

In 1913, the railway started more projects on the west side of the Cascade mountains. They built more tunnels and snow sheds. For example, the Windy Point Tunnel was about 1,200 feet (366 m) long. It allowed two tracks to run along a very steep cliff. Another interesting tunnel was the Martins Creek tunnel, also called the Horseshoe Tunnel. It curved almost 170 degrees, with tracks crossing over Martin Creek twice on bridges. These new snow sheds used a mix of wood and concrete.

Keeping these sheds in good repair was very expensive. So, in 1909, the railway started using electricity to power their trains. They also realized they needed an even simpler and safer route through the mountains.

John Frank Stevens: The Man Behind the Pass

John Frank Stevens is the person Stevens Pass is named after. He was born in 1853 and grew up on a farm. Like many engineers back then, he didn't go to college for engineering. Instead, he learned by working for railroads. He started by surveying land and working as a section hand.

Before working for James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway in 1889, Stevens had already planned routes for many western railroads, including the Canadian Pacific. He was known for being a very skilled and hardworking engineer. He faced many challenges in his travels, like being chased by animals, getting sick, and being stuck in blizzards. He was very tough and seemed able to handle any weather.

The Great Northern Railway was known for being very well-designed, and much of that credit goes to Stevens. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt chose him to be the Chief Engineer for the Panama Canal. This was a very difficult job, but Stevens got the project moving forward.

He returned to work for James J. Hill in 1909. Later, in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked him to go to Russia to help with their railways. He stayed there as an advisor until 1922. In 1927, he became the president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. In 1937, when he was 83 years old, he even flew to the Panama Canal in a plane! John Frank Stevens passed away on June 2, 1943.

Further Reading

- Anderson, Eva G. Rails Across the Cascades. Wenatchee Wenatchee World Publishing Company, 1952 (?)

- Hult, Ruby El. Northwest Disaster: Avalanche and Fire; Portland: Binfords & Mort, 1960

- Sandstrom, Gosta. Tunnels. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.

- "Concrete and Timber Snowsheds on the Great Northern Railway". Engineering News, Vol. 36 No. 24 (December 15, 1910).

- "Tunnels and Snowsheds in the Cascades: Great Northern Railways". Engineering News, Vol. 71 No. 23 (June 4, 1914).

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |