Susan Sweney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Susan Sweney

|

|

|---|---|

Susan Sweney in 1936

|

|

| Born |

Susan Dorothea Mary Therese Sweney

2 February 1915 Trichinopoly, British India

|

| Died | 30 October 1983 (aged 68) Surrey, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Journalist and broadcaster |

| Known for | Propaganda broadcasts from Nazi Germany |

Susan Dorothea Mary Therese Hilton (born Sweney, 2 February 1915 – 30 October 1983) was a British radio broadcaster. She worked for the Nazi government in Germany during World War II.

Susan was born in India to a British family with Irish roots. In the 1930s, she joined the British Union of Fascists. This was a political group in Britain. After some issues with the police, she planned to join her husband in Burma. However, her ship was sunk in the Indian Ocean by a German ship. She was rescued and sent to France.

On the way to France, her second ship was also attacked and sunk by a British submarine. She was rescued again. She later joked that she had been "many times drowned."

She started working as a journalist in Paris. Then she moved to Berlin. There, she made radio broadcasts to support the Nazi government. She sometimes made mistakes during her broadcasts. This led to her being let go from some jobs.

Later, in Vienna, she worked for the Schutzstaffel (SS). This was a powerful Nazi organization. She helped watch people suspected of spying for the Allies. She herself came under suspicion from the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. She was arrested but later released. She was sent to an internment camp.

After the war, she was returned to Britain. She was tried for helping the enemy and was sent to jail for 18 months. After her release, she worked as a courier and later in a pet shop business.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Susan Sweney was born in Trichinopoly (now Tiruchirappalli), British India. Her birthday was 2 February 1915. Her parents were British, with family connections to Ireland. Her father, Cyril Edward Sweney, was a railway police superintendent. Her mother was Dorothy Sweney.

Susan had a brother named Edward. He was born in India and later became a farmer in Ireland. Susan went to school partly in England. Her brother said she had a "rough treatment" there. This experience may have made her feel unhappy about the British class system. It might have shaped her political ideas.

In 1936, Susan married George Martin Hilton. He was a Scottish mining engineer. They had a son who sadly died young. George Hilton later became a captain in the Royal Engineers. He worked with the Special Operations Executive during World War II.

Joining Political Groups

In 1936, Susan Sweney joined the British Union of Fascists (BUF). This was a political group in Britain that believed in strong national control. She felt she believed in their ideas. She was an active member of the group. In October 1936, she had some trouble with the police near 10 Downing Street.

Her husband said she went to a Nazi party meeting in Munich in 1938. Susan left the BUF that same year. She disagreed with the party's approach to Jewish people. She felt that attacking them would only cause problems. She then moved to Dublin, Ireland. The Irish police watched her activities there.

By January 1940, Susan was back in London. She rejoined the BUF. She became the editor of a newspaper called Voice of the People. She worked there from January to May 1940. The police later searched her flat and took her materials. She had already planned to leave the job. She wanted a quieter life after her young son passed away. She had booked a trip to join her husband in Burma.

Two Shipwrecks

Susan left for Burma on a ship called the Kemmendine on 28 May 1940. However, a German ship called the Atlantis captured and sank the Kemmendine. This happened in the Indian Ocean on 13 July 1940. The crew and passengers were moved to the Atlantis.

On the Atlantis, Susan was known for her strong opinions. She sometimes argued with the crew. The first officer, Ulrich Mohr, remembered that she was upset about the ship's bartender. He said she could be calmed with some Scotch whisky. After she left the Atlantis, Mohr found letters. These letters suggested Susan's husband, George, was suspected of spying for the Japanese in Burma.

Susan and the other survivors from the Kemmendine were moved to another ship. This was the Norwegian ship Tirranna, which the Atlantis had also captured. They sailed towards France with a cargo of stolen goods. Susan said that on the Tirranna, the Germans began to see her as Irish, not British. This was because she became friends with Thomas Cormac MacGowan. He was a 54-year-old Irish doctor from the Kemmendine.

On 22 September, the Tirranna was attacked. A British submarine called Tuna torpedoed it off the coast of France. The ship sank, and 87 people lost their lives. The survivors were taken to a German naval base in Royan. From there, Susan and MacGowan traveled to Paris in December 1940.

Life in Paris

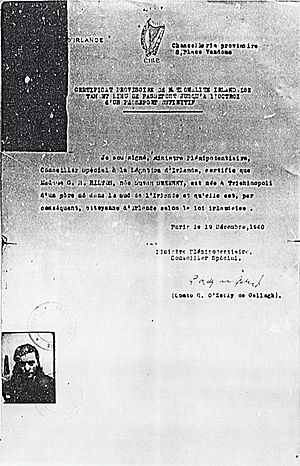

In Paris, Susan got a temporary Irish identity document and passport in December 1940. Many people who claimed to be Irish in occupied Paris received such documents. Her British passport had been taken by the Germans before she arrived in France.

She made a radio broadcast about her adventures. The Germans paid her 500 Reichsmarks for it. This broadcast was picked up by BBC Monitoring in April and May 1941. They noted that she spoke about how well the German crew treated the passengers. She also mentioned how many lives were lost when the Tirranna was sunk by the British. Her broadcast was later published in Hamburg in 1942. It was titled "An Irish woman's experience of England and the war at sea." The title accepted Susan's claim to be Irish.

Susan lived at the Hotel d'Amerique in Paris. She started working as a journalist. Some people at the time said she had good relationships with high-ranking German officers. She later told British intelligence that she helped an Irish priest, Father Kenneth Monaghan. She claimed they helped British merchant sailors escape from Paris. Monaghan had been a British Army officer and had connections to MI6. Another Irish woman in Paris, Winifred Fitzpatrick, supported Susan's story after the war.

In June 1941, Susan was visited by two German agents. They asked her to do secret work for Germany. She was given money and fake identity papers. She traveled to Berlin, where they discussed the secret work again. She understood it might involve traveling to Ireland, the United States, or Portuguese East Africa. She refused, saying the work was too "dirty." However, she was given other tasks. These included listening to phone calls and visiting military sites. This was for a propaganda book about German military strength.

Working in Berlin

From September 1941, Susan Sweney worked for Büro Concordia. This was part of the German foreign ministry. It ran secret radio stations. These stations pretended to be from inside other countries. They aimed to make people think that local groups were broadcasting, not Germany. Susan made broadcasts to Scotland as "Ann Tower" on a station called Radio Caledonia. The name "Tower" came from her mother. She also got a German passport with that name. She also prepared religious material for another station.

From January 1942, she worked at Irland-Redaktion. This was a radio station focused on Ireland. She used her maiden name, Susan Sweney, there. She wrote talks for others and presented her own talks three times a week. She admitted these were "sheer propaganda." Their goal was to keep Ireland neutral during the war. She also wrote plays and recited poetry that was broadcast to America.

In March 1942, she sent a letter to her brother Edward in Ireland. She signed it "your many times drowned sister, Susan." Edward never received the letter. It was read by the Gestapo, British intelligence, and Irish intelligence. This accidentally alerted them to her activities. Her brother was even visited by a British representative, the poet John Betjeman.

In May 1942, she wrote to a friend in Dublin, Biddy O'Kelly. She described her work and asked how her broadcasts were received in Ireland. She wondered if she would be able to return there after the war. She also asked about her husband. She did not know what had happened to him. Her husband later told his superiors in 1944 that they had not been close for some years. Susan mentioned enjoying smoking a pipe and spending time with Sophie Kowanko. Sophie was a colleague at Irland-Redaktion.

In June, Susan wrote again, saying:

I have never felt so completely homesick and cut off as I do now. Biddy, nothing can make up for these years of unbelievable loneliness. I try to shake off these sad thoughts. I go to races and bet as much as I can. I work hard to forget.

Susan became very close with Sophie Kowanko. Sophie was born in 1916 and grew up in Paris. She was the daughter of Russian immigrants. Sophie was educated in England and Italy and spoke many languages. She worked as a typist at Irland-Redaktion. However, she also had a bigger role. She made a weekly broadcast to Irish women as "Linda Walters." The two women shared an apartment in Berlin's Klopstockstrasse. They spent time together. When Sophie had problems with the Gestapo, Susan worked to get her released. She succeeded in getting Sophie a six-month contract at Interradio at the end of 1942.

Many of Susan's broadcasts were harmless. An Irish diplomat found her to be open in her criticisms of both Germans and British. However, she needed to earn money. This helped her Nazi bosses control her. She was a young woman in a foreign country with few friends. She could not leave. So, she had to present whatever material she was given. Sometimes this included anti-Jewish content. For example, her broadcast on 19 July 1942 used statistics to present a false picture of a growing Jewish population in the United States. However, such material was not common in her broadcasts. The station's managers felt it was too harsh for their audience. Instead, Irland-Redaktion focused on anti-war and anti-British messages. They stressed the importance of Irish neutrality.

For example, in July 1942, she broadcast:

Two years ago, I believed Churchill's lies. He said the British Navy had cleared the seas of Nazi ships. Two years ago today, I suffered for my foolishness in the Indian Ocean. Everyone should learn from my experience that Churchill is a liar. The future looks bad for Britain and her Allies. But it has always been bad – Only Churchill never admitted it.

Susan was let go from Irland-Redaktion in autumn 1942. This was after she made mistakes on air. But she started working again in January 1943 at Interradio. She said, "Sonja and I wanted to be together." She worked there until June 1943, writing scripts but not broadcasting. Sophie Kowanko returned to her family in Paris in mid-1943. Susan sent her money when she could.

Susan was a fluent English speaker and an experienced radio presenter. So, the Nazi propaganda machine wanted her. From January to October 1943, she worked for the German Foreign Office. She prepared talks called Voice of the People. In 1943 and 1944, she also wrote anti-communist articles. In mid-1943, she was asked to tour Germany's main cities. She was to write an article for foreign readers about the Catholic Church. It would focus on churches damaged by Allied bombing. This was to counter the Allied idea that the Nazis were destroying the church. However, the Gestapo began to follow her. For unknown reasons, they suspected her of being an Allied spy.

Time in Vienna

In July 1943, Susan was allowed to move to Vienna. A sculptor named Lisa von Pott helped her find a place to stay. She lived with Mrs. Luze Krimann. Mrs. Krimann was a strong supporter of the Nazis. However, her husband was later grounded for being politically unreliable. He then left the army in February 1945. Mrs. Krimann remembered that Susan mostly typed for a magazine or slept. Susan also made short broadcasts for Voice of the People. She was always short on money. Mrs. Krimann told British intelligence that Susan claimed she had turned against the war. But she felt she had no choice but to continue writing anti-British propaganda. She knew she would have to explain her actions if Germany lost.

In October 1943, Susan's work for the Foreign Office ended. She felt "stranded." However, she soon found a new job. She worked for what British intelligence called the "Von Pott Group." This group was organized by Lisa von Pott. Its purpose was to spy on anyone in Vienna suspected of helping the Allies. Lisa von Pott recruited Susan. She asked Susan if she wanted to work against communists. When Susan agreed, she was introduced to Dr. Robert Wagner. He was an SS officer. He met Susan weekly.

Susan admitted to watching several people. These included Doris Brehm, Count Leo Zeppelin, Dr. Alphons Klingsland, and all Americans in Vienna. But she claimed she tried to warn them they were at risk. She said she only did the work hoping to escape to Yugoslavia. However, witnesses later disagreed with her claims. They believed she had reported them to the SS or Gestapo.

For example:

- Herbert P. Erdmann accused Susan of "high treason and espionage against England." He said she reported him to the German secret police in June 1944.

- Alphons Klingsland, a lawyer, said Susan visited him twice. She tried to get him to help her. He refused because he found her suspicious. He felt she tried to involve him in things that could have put him in trouble with the Gestapo. He also said Susan never warned him. He was later reported to the Gestapo by someone unknown.

- Felix Krimann, the army deserter, also claimed Susan reported him to the Gestapo.

Among Lisa von Pott's friends was Countess Amethé von Zeppelin. She was a British woman married to Count Leo Zeppelin. British security services believed she was anti-British even before the war. She had made an anti-British radio broadcast from Vienna in September 1939. Susan later had a visiting card from the countess. It had a secret message in German.

In 1944, Susan visited the Turkish consulate in Vienna. She tried to get a visa to leave Nazi Germany. But the Gestapo found out and arrested her in July. Her friend, Margaret Schaffhauser, said Susan was in a "condemned cell" in Vienna. But after she was saved, "a great calmness came over her there. She was no longer on the run."

Internment and Release

In August 1944, Susan was sent to Liebenau internment camp. This camp was for women and children in southern Germany.

Susan was on the "British Renegades Warning List." This list was made by British security services before the Normandy landings. It helped Allied troops identify people who might try to harm the invasion. After Liebenau was freed, Susan was held there for eight months. She was questioned by MI5, a British intelligence agency. Most other prisoners were released.

Before sending her back to Britain, MI5 had to confirm Susan's nationality. If she was a citizen of a neutral country, she could not be accused of helping the enemy.

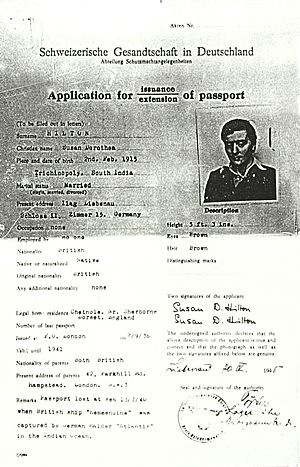

Susan stated that she thought her father was born in Ireland, but she was not sure. She received a British passport in 1936 because her husband was British. She lost it before arriving in France. She was released from detention in France. She then got a temporary Irish identity document and passport in Paris. But the Germans replaced that with a "foreigner's passport" when she reached Berlin. She tried to get new Irish papers, but Irish diplomats in Berlin told her she had no claim to citizenship. In 1945, while in the camp, she applied for a Swiss passport. It is not known if she received it.

Arrest and Court Case

Susan was returned to Britain in December 1945. She was with Iris Marsden, an MI5 officer. Marsden later remembered that Susan's arm was in a cast. She thought French soldiers might have hurt her. According to Marsden, Susan was "devious" and the evidence against her was "damning." Susan knew what she had done and was very scared. She told Marsden that the internment camp had been "the safest place to be." This supported the idea that she had asked to be interned.

Susan was arrested when she arrived at Victoria Station in London. She later appeared in court. She was charged with helping the enemy by working for German radio propaganda. Her court case was on 18 February 1946. It took place at the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey). She faced ten charges of helping the enemy. She admitted to eight of them. Two charges she denied were dropped. These were that she had joined the SS and that she had planned with others to broadcast propaganda. She was sentenced to 18 months in jail.

The court case lasted less than a day. This meant that much of Susan's life in Germany was not mentioned. For example, that she had first refused spying work. Or that the Gestapo had arrested her. Her brother, Edward, later told historian David O'Donoghue that he felt she did not get a fair trial. He believed his sister was only seeking peace and was "innocent of any blameworthy act." He described her as an "exhibitionist," "very immature and driven by fame." He also said she was "a person who needed a good deal of guidance. She was easily led, highly volatile, a very impressionable person, generous but hot-tempered."

Susan herself later believed that her short trial and the mild treatment she received in Holloway prison suggested something else. She thought she was being used to hide other British spy activities. Perhaps a British female agent had been on the Kemmendine ship. According to her friend Margaret Schaffhauser, this was the only way Susan could explain what happened.

Later Life

Susan told Margaret Schaffhauser that when she left prison, two MI5 agents met her. She always called them "my friends." She said they went out of their way to help her. They stopped a planned book about her. They told her to contact them if anyone said anything bad about her. Susan claimed they sent her Christmas cards every year until they retired.

After prison, she worked as a courier. She traveled to Australia and South America. Later, she worked for a farm and pet shop business in England. Susan Sweney died in Surrey, England, on 30 October 1983.

In 1998, after David O'Donoghue's research for his PhD, her brother Edward asked the British Home Secretary Jack Straw to reopen her case. He felt it was an unfair judgment. A file of official papers about Susan was released by the British National Archives in 2001.

Images for kids

See also

- List of English-language broadcasters for Nazi Germany

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |