Sydney Harbour railway electricity tunnel facts for kids

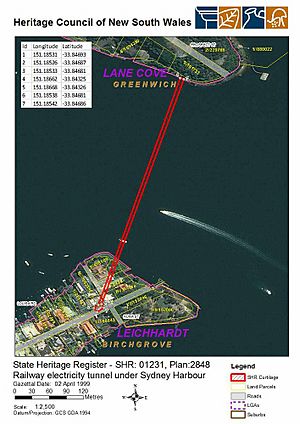

Quick facts for kids Sydney Harbour railway electricity tunnel |

|

|---|---|

Heritage boundaries

|

|

| Location | under Sydney Harbour between Birchgrove and Greenwich, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Official name: Railway electricity tunnel under Sydney Harbour; Sydney Harbour tunnel; Balmain to Greenwich Electric Cable Tunnel | |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 1231 |

| Type | Other - Utilities - Electricity |

| Category | Utilities - Electricity |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Sydney Harbour railway electricity tunnel is an old, important tunnel under Sydney Harbour. It connects the areas of Birchgrove and Greenwich in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. People also call it the Balmain to Greenwich Electric Cable Tunnel.

This tunnel was built to carry special electricity cables. These cables powered the electric tram and train systems in Sydney. It is considered a heritage site, meaning it's an important part of history. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on April 2, 1999.

Contents

Why Was the Tunnel Built?

The tunnel was constructed between 1913 and 1926. It runs from Long Nose Point in Birchgrove to Manns Point in Greenwich. Its main job was to protect electricity cables. Before the tunnel, these cables lay on the bottom of Sydney Harbour. But ships and their anchors often damaged them.

Building this tunnel was a huge engineering challenge for Australia at the time. It was the very first tunnel ever completed under Sydney Harbour.

Early Tram and Train Power Needs

Electric trams started running on the north side of Sydney Harbour in 1893. The first route went from Falcon Street in North Sydney to Spit Road. By 1904, many steam trams south of the harbour were becoming electric.

Power stations at White Bay and Ultimo were making more electricity. A new substation was built in North Sydney to power the growing tram system. Cables were laid across the harbour floor to send power from White Bay to North Sydney.

The shortest path for these cables was between Long Nose Point and Manns Point. By 1912, more cables were needed for the expanding tram network. To keep these new cables safe, engineers decided to build a tunnel. Work on the tunnel began in October 1913.

Steam trains also ran from Hornsby to Milsons Point. This train service became electric in 1927, just after the tunnel was finished.

Building the Tunnel: A Big Challenge

Building the tunnel was very difficult. Workers started digging from three different places: Long Nose Point, Greenwich, and a shaft at Manns Point.

The First Attempt

At first, digging went quickly. However, problems soon appeared. People living near Long Nose Point complained a lot. Because of their protests, work from that end had to stop.

So, digging continued slowly from the north side. In May 1915, workers hit a large crack in the rock. This crack was right in the middle of the harbour. Water, sand, and mud started rushing into the tunnel.

To fix this, they built a wall inside the tunnel to stop the water. Then, they built a platform in the middle of the harbour. They drilled holes through the riverbed and pumped cement into the crack. This sealed the tunnel. They repeated this process, sealing the tunnel twice.

After opening it again, they found the seal was weak. So, they decided to abandon this upper tunnel. They built a permanent concrete wall and sealed it up. This part of the tunnel remains sealed today.

The Second, Deeper Tunnel

Engineers decided to start a new tunnel. This second tunnel was dug about 15 metres (50 feet) below the first one. The slope inside the tunnel became steeper.

Work continued with explosives. But when they reached the spot directly under the first crack, they hit another crevice. Water flooded the tunnel again.

The engineers, R. L. Rankin and W. R. H. Melville, bravely swam into the flooded tunnel. They used candles on wood to see. They found the crack and planned how to seal it. It was a very risky job.

To seal this new crack, they put pipes into it. They packed the area with bags of clay. Then, they built a strong steel wall with a door. Through other pipes, they pumped cement into the crack under high pressure. This was left to set for about three months.

When the door was opened, the water inflow had almost stopped. The clay bags had turned into solid cement. Workers then dug a small detour around the sealed crack. After passing it, they returned to the original tunnel path.

Later, they hit another small crack, which was part of the first one. Water flowed in at about 10,900 litres (2,400 imperial gallons) an hour. This wasn't enough to stop work, but pumps were installed to remove the water.

As workers dug uphill, they had to be very careful. Special machines cut out the rock. Finally, they broke through to the Long Nose Point side. Their measurements were incredibly accurate. The tunnel's centre line was only 3 millimetres (1/8th of an inch) off, and the levels were perfect.

The Tunnel Today

Even after careful lining, the tunnel sometimes leaked. Around 1930, the tunnel was flooded. It's not clear if this was done on purpose to avoid constant pumping, or if water rushed in suddenly.

In 1952, the Electricity Commission of New South Wales took over electricity generation. The tunnel and its cables remained owned by the State Rail Authority. During the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, some railway communication cables were moved to the Bridge.

The electricity cables in the flooded tunnel continued to be used until 1969. However, they are no longer needed. Today, the north side of Sydney Harbour gets plenty of electricity from other substations.

Inside the Tunnel

The tunnel's walls are made of concrete in some parts, cast iron in others, and natural rock in still more. In the middle, there's a large room where pumps used to remove water.

Along one side, there are concrete racks. These racks held the high-voltage wires that supplied power for trams and trains. The tunnel could hold twelve cables: eight 11,000-volt cables and two communication cables. At one end, there was a pool about 1.8 metres (6 feet) deep to collect water that seeped in. This water was then pumped to the surface.

The tunnel is mostly straight. It only bends at Greenwich Point to allow an exit. From one end to the other, it is about 536 metres (1,760 feet) long. At each entry point, it goes steeply down into the ground.

Today, there are no signs of the Birchgrove entry point above ground. But the shaft, tunnel, and old cables are still there underground. They are important evidence of the major infrastructure built by the State Rail.

Why is it a Heritage Site?

The Sydney Harbour railway electricity tunnel was a huge achievement in technology and engineering. It was the first project of its kind in Australia built without help from other countries.

It played a vital role in supplying power to the railway and tram systems between Sydney and the North Shore. Even though it is now flooded, it is still an important part of how public transport developed in Sydney.

The Sydney Harbour railway electricity tunnel was officially listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on April 2, 1999.

Images for kids

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |