Tacky's War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tacky's War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Slave Revolts in North America | |||||||

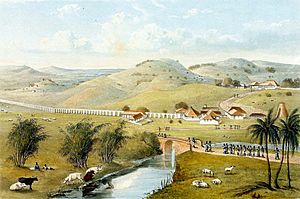

Trinity plantation, one of the first to be captured by the rebel slave |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Maroon allies |

Enslaved "Coromantee" people - likely of Ashanti, Fante and Akyem origin | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Tacky † Apongo (a.k.a. Wager) Simon/Damon |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 70 - 80 mounted militia Many Maroon allies |

Hundreds | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60 whites, 60 free blacks | 400 black slaves in St Mary, 700 in western Jamaica, Over 500 recaptured and resold |

||||||

Tacky's War, also known as Tacky's Revolt or Tacky's Rebellion, was a big fight for freedom by enslaved people in the British Colony of Jamaica during the 1760s. This uprising was led by Akan people (also called Coromantee), including tribes like the Ashanti and Fante. The main leaders were Tacky (Takyi) in eastern Jamaica and Apongo in the western part of the island.

Tacky's War was the most important slave uprising in the Caribbean between the 1733 slave insurrection on St. John and the Haitian Revolution in 1791. Some historians say that only the American Revolution had a bigger impact on the British Empire in the 1700s. It was the most dangerous slave rebellion in the British Empire until the Baptist War of Samuel Sharpe in 1831–32, which also happened in Jamaica.

Contents

- Planning the Fight for Freedom

- Tacky's Rebellion Begins

- Tacky's Defeat and Death

- After Tacky's Revolt

- Akua, "Queen of Kingston"

- Apongo and the Western Revolt

- The Western Revolt Begins

- British Military Takes Control

- Apongo's Defeat and Death

- The Rebellion Under Simon

- Other Uprisings in the 1760s

- Aftermath of the Revolts

- Plaque Moved from Church

- Images for kids

Planning the Fight for Freedom

Enslaved people in Jamaica faced very harsh conditions. Many people at the time said that the way slaves were treated in Jamaica was among the most brutal in the world.

The leader of the rebellion, Tacky (originally spelled "Takyi"), was from the Fante group in West Africa. He had been a powerful chief or warlord in his home country before he was captured in battle and enslaved. Tacky and his trusted friends planned to take over Jamaica from the British. Their goal was to create a separate country for black people. This uprising was inspired by the success of Free black people in Jamaica, like the Jamaican Maroons and Asante Queen Nanny, who had fought for their freedom in the 1730s.

Before becoming enslaved, Tacky was a king in his village. He had even sold prisoners from rival groups into slavery. But, in a twist of fate, he himself became enslaved when a rival group and the Dutch defeated his army. He was then sold into slavery and ended up in Jamaica.

Tacky and his friends, including Quaw Badu, Sang, Sobadou, Fula Jati, and Quantee, planned the revolt in secret. Most of them were of Akan descent. This slave revolt was a carefully planned effort across the entire island, organized by a secret network of Akan (Coromantee) enslaved people.

Tacky's Rebellion Begins

Early on Easter Monday, April 7, 1760, Tacky and his followers started their revolt. They quickly took control of the Frontier and Trinity plantations, killing some of the white overseers. Zachary Bayly, who owned Trinity, was not killed.

Enslaved people from the Esher estate also joined Tacky's forces. They marched to Fort Haldane, where weapons for the town of Port Maria were stored. After killing the storekeeper, Tacky and his men took gunpowder and firearms. Then, they moved on to take over the Heywood Hall and Esher plantations.

By dawn, hundreds of other enslaved people had joined Tacky. At Ballard's Valley, the rebels celebrated their early success. One enslaved person from Esher managed to escape and warn the authorities. Obeahmen (spiritual leaders) went around the camp, giving out a powder. They claimed this powder would protect the men from harm in battle. They also loudly said that an Obeahman could not be killed. Everyone felt very confident.

On April 9, the governor sent soldiers from Spanish Town to Saint Mary Parish, Jamaica. These soldiers were joined by Jamaican Maroons from Moore Town, Charles Town, and Scott's Hall. The Maroons had a treaty that forced them to help stop such rebellions.

Tacky's rebels burned houses in St Mary. On April 12, the soldiers and Maroons met Tacky's men. Tacky's men attacked, killing some white soldiers. Tacky himself was reportedly wounded.

Tacky's Defeat and Death

Captain William Hynes and the Maroons chased Tacky through the mountains. They fought Tacky's men in a rocky area and captured some rebels. The next day, April 13, the Maroons continued to pursue Tacky's men.

When the soldiers learned about the Obeahman's claim of being unkillable, they captured an Obeahman. They killed him and hung his body with his mask and decorations in a place where the rebels could see it. This shook the confidence of many rebels, and many returned to their plantations. Tacky reportedly agreed to keep fighting with only about 25 other men.

On April 14, more Maroons joined the chase. They fought Tacky's men in Rocky Valley, defeating and killing many of them. Tacky and his remaining men ran through the woods. A famous Maroon marksman named Davy shot Tacky. Davy cut off Tacky's head as proof, for which he was greatly rewarded. Tacky's head was later displayed on a pole in Spanish Town.

After Tacky's Revolt

In May and June, some of Tacky's men who had surrendered were executed. One rebel was hanged, and another was burned. Two others were hung in chains and starved to death.

In June 1760, similar plans for revolt were found in other parishes. In St Thomas-in-the-East, a rebellion was stopped when a rebel named Cuffee told the authorities. Nineteen rebels were then executed. Other planned revolts were also revealed by rebels. In one case, four rebels were executed, and six others were sold into slavery in a nearby Spanish colony.

Akua, "Queen of Kingston"

It was also discovered that enslaved Coromantee women in Kingston had chosen a Fante woman named Cubah (also known as Akua) as their 'Queen of Kingston'. Akua would sit under a special cover during their meetings, wearing a robe and a crown. Fante stories say that Akua Seisewaa was a powerful queen mother who was sent away and sold into slavery by the British because she was difficult.

It is not known if Akua's group had direct contact with Tacky's group. When she was discovered, she was ordered to be sent away from the island for planning a rebellion. While at sea, she paid the ship's captain to let her off in western Jamaica. There, she joined the rebels and stayed hidden for months. When she was caught again, she was executed.

Apongo and the Western Revolt

The revolt did not end with Tacky's death. Other rebellions broke out across Jamaica, many inspired by Tacky's actions. About 1,200 rebels gathered in the mountains of western Jamaica. They were led by a rebel named Apongo (also called Wager). They attacked several plantations in Westmoreland Parish and Hanover Parish, killing some white people.

Apongo had been a military leader in West Africa before he was captured and brought to Jamaica as a slave. His enslaver in Jamaica renamed him Wager. Apongo organized a rebellion that started on April 7, 1760, and continued until October of the next year. Some historians believe Apongo's rebellion in western Jamaica was even more important than Tacky's uprising.

According to a planter named Thomas Thistlewood, Apongo was a "prince in Guinea" who had been captured while hunting and sold into slavery.

The Western Revolt Begins

Enslaved people shaved their heads to show that the uprising was about to begin.

On May 25, the western rebellion started on the Masemure estate in Westmoreland. One of Apongo's leaders, Simon, fired the shot that killed the estate manager, signaling the start of the revolt. The rebels had planned their uprising to happen when a naval ship was leaving the bay, thinking security would be weaker.

Apongo later said he had planned to attack the bay, but some of his leaders wanted to fight in the mountains instead.

The rebels were well-prepared to fight back against the soldiers. After an attack on the rebels' stronghold, soldiers found gunpowder, clothes, and other supplies. White and black refugees fled to the capital of Westmoreland, Savanna-la-Mar. Soldiers fought back, capturing and killing many rebels. Many of those captured were quickly executed without a trial.

On May 29, soldiers tried to attack the rebels' barricaded camp but were defeated. This success brought more recruits to the rebels and caused many soldiers to leave their posts.

British Military Takes Control

The governor again declared martial law, meaning the military took over.

British soldiers and Maroons from Accompong Town joined the fight. On June 1–2, these forces successfully attacked the rebel stronghold after a two-hour battle. They killed and captured many rebels. During the battle, many rebel men, women, and children were forced over a steep cliff and fell to their deaths. Hundreds of rebels may have died. Many were quickly executed after being captured.

However, even with this big victory, the colonial armies found it hard to fight against the smaller groups of Apongo's rebels who used guerrilla warfare. On June 5, the British military commander found that only the Maroons from Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town) were having success against the rebels. These Maroons killed more than a dozen rebels and captured 60 others.

The rebel enslaved people continued fighting for the rest of the year in western Jamaica. This forced the governor to keep martial law in place.

On June 7, there were uprisings in Saint James Parish, Jamaica and Hanover. However, the rebels' attempts to take plantations were stopped by planters, their workers, and loyal enslaved people. The Maroons then ambushed the rebels, killing several, but most escaped.

On June 10, soldiers defeated a group of rebels, killing about 40 and capturing 50. On June 20, the soldiers killed and captured 100 rebels. On June 22, one rebel was quickly tried for killing two white children. After being found guilty, he was burned alive.

That same day, another uprising was stopped, and over 60 enslaved people were captured. Most were quickly executed. However, many more escaped into the Cockpit Country, where they joined Apongo's rebels. These smaller rebel groups moved through the mountains and forests to avoid being caught by soldiers and Maroons.

Apongo's Defeat and Death

Many rebels were killed in the western conflict. People reported the smell of death from nearby woods, and colonists found hanging bodies of African men, women, and children.

Rebels surrendered every day. On July 3, Apongo, the "King of the Rebels," was captured. Another rebel was executed by being left in a cage to starve to death, which took a week. Apongo himself was hung in chains for three days. He was supposed to be burned to death afterward, but he died in his cage within those three days, escaping the final part of his sentence.

The Rebellion Under Simon

The remaining rebels then followed an escaped enslaved person named Simon. They hid in the Cockpit Country and attacked nearby plantations. In October, they attacked and destroyed the Ipswich sugar estate. In December, Simon's rebels burned a house and shot another white man.

Simon's rebels were about 50 armed men and women. Their goal was to gain recognition for their freedom, similar to the Maroons.

Later, groups sent to hunt Simon's rebels reported killing some of them. They cut off their heads and put them on poles. However, Simon and most of his rebels escaped.

In January 1761, Simon's rebels moved to a new location. There were reports that Simon was shot and killed in a fight with soldiers.

Even after Simon's death, his group continued to raid western estates, possibly under a new leader. By late 1761, the governor said that the main western revolt was over. However, some remaining rebels continued to operate in small groups from the forests of the Cockpit Country. They carried out guerrilla warfare for the rest of the decade, raiding plantations.

In 1763, groups of rebels attacked plantations, killing several white people. The new governor had to deal with this crisis with the help of the Trelawny Town Maroons.

Other Uprisings in the 1760s

The rebellions led by Tacky and Apongo continued to inspire other uprisings throughout the 1760s. In 1764, authorities found a new plan for revolt.

In 1765, another uprising in St Mary led to enslaved people setting a plantation on fire. This revolt was led by Abruco, who had been accused of being involved in Tacky's Revolt but was found not guilty. This time, Abruco was sentenced to be burned alive, while other rebels were hanged or sold away.

In October 1766, another rebellion happened in Westmoreland, also inspired by Tacky's Revolt. About 33 Akan enslaved people rose up and killed 19 white people before the revolt was stopped. Rebels who were found guilty were sentenced to be burned alive.

Most of the remaining rebels then moved to the mountains of Nassau Mountain.

Aftermath of the Revolts

It took months, and even years, for order to return to Jamaica. Over 60 white people and a similar number of free people of color lost their lives. About 400 enslaved black people were killed, including two leaders who were burned alive. More than 500 rebel enslaved people were "transported," meaning they were sold again to new owners in the British colony in Honduras. The damage caused by Tacky's Revolt and other uprisings cost Jamaica a lot of money.

After Tacky's Revolt, the colonial government passed strict laws to control enslaved people. They also banned West African religious practices like obeah.

Today, you can visit the Tacky Monument in Claude Stuart Park in Port Maria. Tacky Falls is also nearby, but it's hard to reach by land. The exact location of the cave where Tacky's men were found is not known.

Tacky's Rebellion, like many other slave revolts, was put down quickly and harshly by the colonial officials. Planters severely punished the rebels. However, the smaller rebellions continued for months and even years after the main revolt was crushed. There is no record of Simon's runaway communities being completely destroyed. It's possible they joined other successful runaway communities later on, and they may have inspired other slave revolts.

A historian named Robert Charles Dallas wrote that in the 1770s, a community of runaway enslaved people formed the Congo Settlement. They resisted efforts by the Accompong Maroons to break them up until the end of the century. It is possible that Simon's rebels and those from the 1766 Revolt became part of these Free black people in Jamaica. Many survivors of this community later fought alongside the Trelawny Town Maroons in the Second Maroon War.

Plaque Moved from Church

In May 2023, a plaque honoring plantation owner John Gordon was moved from St Peter's Church, Dorchester in England to the nearby Dorset County Museum. This plaque had language that was seen as racist and praised his role in stopping the rebellion. The offensive part of the plaque had been covered since September 2020.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |