Tanistry facts for kids

Tanistry was an old Gaelic way of passing on important titles and lands. Imagine a family or a group of people (called a clan) where the leader was a king or a chief. Instead of the oldest son automatically taking over, the next leader, called the Tanist, was chosen.

The Tanist (pronounced TAW-nist) was like the second-in-command or the person next in line to become the chief or king. This system was used by Gaelic families in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man.

Today, the word is still used in the Republic of Ireland. Their prime minister is called the Taoiseach, and the deputy prime minister is called the Tánaiste, which comes from the word Tanist.

Contents

How Tanistry Started

Historically, the Tanist was chosen from a group of people known as the roydammna (pronounced ROY-dav-na). This word literally means "kingly material." These were people who were considered fit to be king or chief. Sometimes, the choice was made from all the men in the entire family group, or "sept."

The selection was done by a vote in a big meeting. Only men related through their father's side (called agnates) could vote and be chosen. This system of choosing leaders based on male family lines was very old in Ireland, likely even older than written history. For example, a story about an ancient king named Cormac mac Airt mentions his oldest son as his Tanist.

In Ireland, this system continued for many powerful families and smaller leaders until the 1500s and early 1600s. Then, it was replaced by English common law, which usually meant the oldest son inherited everything. When Ireland got its first new Chief Herald in 1943, they didn't bring back tanistry. Instead, they recognized Irish chiefs based on primogeniture, where the oldest child inherits.

In Scotland, the way kings were chosen was also based on male family lines until King Malcolm II became king in 1005. He was the first to try and make the kingship hereditary, meaning it would pass down automatically in the family. He did this to stop the fighting that often happened when kings were elected. Since Malcolm only had daughters, he also allowed daughters to pass on the right to the throne. This caused more conflicts later on. Irish kingships, however, never allowed women to inherit the throne.

Who Could Be a Tanist?

The king or chief held their position for life. But they had to be adults, mentally capable, and without any major physical problems. At the same time, a Tanist (the next in line) was chosen under the same rules. If the king died or couldn't rule anymore, the Tanist immediately became king.

Often, a former king's son became the Tanist. But this wasn't because of primogeniture (where the oldest son automatically inherits). The main idea was that the leadership should go to the oldest and most worthy male relative of the last ruler. This meant many people in the larger clan, who were not directly related to the ruling family, were not eligible.

One common rule for being a "roydammna" was that you had to be part of the previous chief's "derbfhine." This was a group of relatives who all shared a common great-grandfather through the male line. Sometimes, it was even stricter, limited to the chief's gelfhine, which included only those descended from one common grandfather. This made the ruling group very exclusive, keeping the kingship within a small part of the family. Many other clan members might become gentry or peasants, even if they shared the same family name.

This system made tanistry a form of elective monarchy, where leaders were chosen, not automatically inherited. It also meant that the outcome of who would be next in line was not always clear, unlike in a hereditary monarchy.

The problem with having many eligible "roydammna" was that it could lead to civil wars within the family. For example, the descendants of King Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair (1088–1156) fought among themselves. His family, the Uí Briúin, had been powerful kings of Connacht. They grew even stronger by taking over other kingdoms like Mide and Dublin. Tairrdelbach became the first of his family to be a High King of Ireland.

However, the competition between Tairrdelbach's many sons caused a lot of fighting. This, combined with the arrival of the Normans in 1169, broke up the Ó Conchobhar family's rule. By the mid-1200s, they controlled only a small part of their original lands.

Another example of how many people could be eligible comes from the Annals of Connacht. It says that at the Second Battle of Athenry in 1316, "twenty-eight men who were entitled to succeed to the kingship of Uí Maine" died alongside King Tadc Ó Cellaig.

What Happened Because of Tanistry?

The tanistry system often caused the leadership to rotate among the most important branches of a family or ruling house, especially during the Middle Ages. Even if it wasn't planned this way, tanistry seemed to create a balance between different parts of the family.

A common pattern was that the chief would be followed by his Tanist, who had been chosen earlier from a different family branch. Then, a new Tanist would be chosen from the branch the deceased chief belonged to. This way, the leadership would keep moving between different parts of the family. If a chief tried to have his own son or brother chosen over someone from another branch, the people who voted would be upset. They worried that one branch would become too powerful.

In 1296, a person named Bruce, who wanted to be king of Scotland, argued that tanistry supported his claim. Under primogeniture, he was from a less direct line of the royal family and wouldn't have been chosen. But the idea of rotation and balance, along with his age and experience, made him a strong candidate. Both the House of Balliol and Bruce families were related to the royal house through female lines, and they were allowed to present their claims. Bruce also claimed tanistry through a female line. This might show that in Scotland, the rules of the Pictish people and the Gaelic people mixed.

The English king decided the argument, favoring the Balliols based on primogeniture. However, later political events led to a more "clannish-tradition" outcome. Robert the Bruce, who was the grandson of the candidate who argued for tanistry, became king even though he was from a less direct line of the original Royal House. After him, all future Scottish kings inherited the throne through the rights of the Bruce family.

Tanistry, as a system of choosing leaders, meant that the top position was open to ambitious people. It often caused fighting within families and between clans. However, it was also somewhat democratic because leaders were chosen. Tanistry was officially ended by a legal decision during the rule of King James VI of Scotland, who later became James I of England and Ireland. English land law then took its place.

The rules for how Scottish monarchs from the House of Alpin (a mix of Pictish and Gaelic origins) were chosen followed tanistry rules until at least 1034. They also used these rules for some successions in the 1090s. Tanistry was even used as an argument in court cases about who should be king as late as the 1290s. A similar system was used in Wales, where under Welsh law any of the king's sons or brothers could be chosen as the edling, or heir to the kingdom.

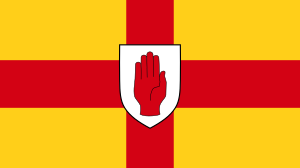

Images for kids

See also

- Agnatic seniority

- Chiefdom

- Chief of the Name

- Clan

- Dynasty

- Elective monarchy

- High King of Ireland

- List of Irish kingdoms

- Mandala (political model)

- Order of succession

- Partible inheritance

- Patrilineality

- Primogeniture

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |