Gelada facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gelada |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male | |

|

|

| Female with baby drinking Both T. g. obscurus near Debre Libanos, Ethiopia |

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Theropithecus

|

| Species: |

gelada

|

|

|

| Gelada range | |

The gelada (Theropithecus gelada), sometimes called the bleeding-heart monkey, is a type of Old World monkey. You can only find them in the Ethiopian Highlands, especially in the Simien Mountains. Geladas are not true baboons, even though they look similar. They are the only living members of their own group, called Theropithecus. This name comes from old Greek words meaning "beast-ape". Like baboons, geladas spend most of their time on the ground, looking for food in grasslands.

Contents

Gelada Family Tree

Since 1979, scientists have usually placed the gelada in its own special group, Theropithecus. Even though some studies suggest it might be related to baboons, other research shows it's quite different. The Theropithecus gelada is the only living species in its group. However, we know from fossils that there used to be larger kinds of Theropithecus monkeys.

Today, geladas only live in Ethiopia. But fossils show that their relatives once lived across Africa, the Mediterranean, and even into Asia.

There are two main types, or subspecies, of gelada:

- Northern gelada, known as Theropithecus gelada gelada

- Eastern gelada, also called the southern gelada or Heuglin's gelada, known as Theropithecus gelada obscurus

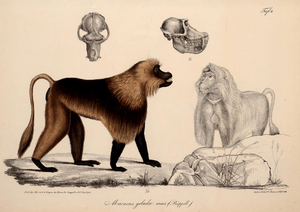

What Geladas Look Like

Geladas are large, strong monkeys. They have thick, coarse hair that can be buff to dark brown. Their faces are dark with light-colored eyelids. Their arms and feet are almost black. They have short tails with a tuft of hair at the end. Adult males have a long, thick "cape" of hair on their backs.

A gelada's face has a short nose, looking more like a chimpanzee's than a baboon's. You can also tell them apart from baboons by a bright patch of skin on their chest. This patch is shaped like an hourglass. On males, it's bright red and surrounded by white hair. On females, it's much less noticeable. However, when a female is ready to mate (in estrus), her chest patch becomes brighter. Small, fluid-filled bumps also form around it. This is similar to how most baboons get swollen bottoms when they are in estrus. Females also have small bumps of skin around their chest patches.

Geladas also have tough pads on their bottoms called ischial callosities. Male and female geladas look different in size. This is called sexual dimorphism. Males weigh about 18.5 kg (40.8 lb), while females are smaller, weighing about 11 kg (24.3 lb). Both sexes are about 50–75 cm (19.7–29.5 in) long from head to body. Their tails are 30–50 cm (11.8–19.7 in) long.

Geladas have special features that help them live on the ground and eat grass. They have small, strong fingers for pulling up grass. Their front teeth are narrow and small, perfect for chewing grass. Geladas have a unique way of moving when they eat, called the "shuffle gait." They squat on two legs and slide their feet without changing their posture. Because of this, their bottom is hidden, but their bright red chest patch is easy to see.

Where Geladas Live and What They Eat

Geladas live only in the high grasslands of the deep valleys in the central Ethiopian plateau. They live at heights of 1,800 to 4,400 meters (about 5,900 to 14,400 feet) above sea level. They use the steep cliffs for sleeping and the mountain grasslands for finding food. These grasslands have trees spread far apart, along with bushes and thickets. The high areas where they live are usually cooler and less dry than lower lands. This means geladas usually don't suffer much from food shortages during the dry season. However, they can experience frost in the dry season and hailstorms in the wet season.

Geladas are the only primates that mainly eat grass. Grass blades make up to 90% of their diet. They eat both the blades and the seeds of grasses. If both are available, they prefer the seeds. They also eat flowers, underground stems (rhizomes), and roots when they can find them. They use their hands to dig for roots and rhizomes. They might also eat herbs, small plants, fruits, vines, bushes, and thistles. They rarely eat insects, and only if they are easy to catch. During the dry season, they eat less grass and prefer herbs. Geladas eat their food more like grazing animals than other primates. They can chew their food as well as a zebra.

Geladas are active during the day (diurnal). At night, they sleep on cliff ledges. When the sun rises, they leave the cliffs and go to the top of the plateaus to eat and socialize. As morning ends, they tend to socialize less and focus mostly on finding food. They will also travel during this time. When evening comes, geladas become more social again before going back down to the cliffs to sleep.

Gelada Behavior

Social Life of Geladas

Geladas live in a very complex society, much like hamadryas baboons. The smallest groups are called reproductive units. These have one to twelve females, their young, and one to four males. There are also all-male units, which have two to fifteen males.

The next level of gelada society is called a band. A band is made up of two to 27 reproductive units and several all-male units. Sometimes, many reproductive units from different bands come together for short times to form large herds of up to 60 units. Communities are made of one to four bands whose home areas overlap a lot. A gelada usually lives for about 15 years.

Within the reproductive units, the females are often related and have strong friendships. If a reproductive unit gets too big, it will split. Even though females have strong bonds, a female will usually only interact closely with up to three other members of her unit. Grooming and other social activities between females usually happen in pairs. Females in a reproductive unit have a ranking system. Higher-ranking females tend to have more babies and more success in raising them. Females who are closely related usually have similar ranks. Females generally stay in their birth units for their whole lives. It's rare for a female to leave. Fights within a reproductive unit are rare and usually happen between females. Fights are more common between members of different reproductive units. Females usually start these fights, but males and females from both sides will join in if the conflict gets bigger.

Males can stay in a reproductive unit for four to five years. While it was once thought that males always leave their birth groups, many gelada males seem to return and have babies in their original bands. Still, gelada males do leave their birth units and try to take over a unit of their own. A male can take over a reproductive unit by fighting directly, or by joining as a helper and then taking some females to start a new unit. If there is more than one male in a unit, only one of them can mate with the females. The females in the group can actually have power over the main male. When a new male tries to take over a unit, the females can choose to support him or not. The male keeps his good relationship with the females by grooming them, not by forcing them to obey. This is different from hamadryas baboons. Females accept a male into the unit by showing themselves to him. Not all females might interact with the male. Usually, one female might be his main partner. This female can sometimes keep the male mostly to herself. The male might try to interact with other females, but they often don't respond.

Most all-male units have several young males and one young adult male, led by one male. A male might stay in an all-male unit for two to four years before trying to join a reproductive unit. All-male groups are usually aggressive towards both reproductive units and other all-male units. But just like in reproductive units, fights within all-male units are rare.

Bands are groups of reproductive units that share a common home area. Members within a band are closely related, and there's no social ranking between the different units in a band. Bands usually break apart every eight to nine years as a new band forms in a new area.

Scientists have seen Ethiopian wolves and geladas together. Studies show that gelada monkeys usually don't move away when they see Ethiopian wolves, even if the wolf is in the middle of the herd. In 68% of meetings, the geladas didn't move, and only 11% resulted in them moving more than 10 meters (about 33 feet). But if they saw aggressive domestic dogs, the geladas always ran far away to the cliffs for safety.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Most gelada babies are born at night. Newborns have red faces, closed eyes, and black hair. On average, they weigh about 464 grams (about 1 pound).

The most babies die during the wet season. But on average, over 85% of babies live to be four years old. This is a big advantage of living where few other animals can eat their food source, so there aren't many large predators.

Females who have just given birth stay at the edge of the reproductive unit. Other adult females might show interest in the babies and even try to "kidnap" them. A baby is carried on its mother's belly for the first five weeks. After that, it rides on her back. Babies can move around by themselves when they are about five months old. A male who is not the main male in a reproductive unit might help take care of a baby when it is six months old.

When large herds form, young geladas and babies might gather into play groups of about ten individuals. When males reach puberty, they form unstable groups that are separate from the reproductive units. Females can have babies when they are about three years old, but they usually don't give birth for another year. Males reach puberty at about four or five years old. However, they usually can't have babies yet because of social rules and have to wait until they are about eight to ten years old. The average life span in the wild is 15 years.

How Geladas Communicate

Adult geladas use many different sounds to communicate. These sounds are for things like staying in touch, comforting each other, making peace, asking for something, showing mixed feelings, being aggressive, and defending themselves. The sounds they make are thought to be almost as complex as human speech. They sit around and chatter to each other, showing that they care about the individual who is "speaking." The sounds they make can also show their social status. Females also have special calls that signal when they are ready to mate.

Geladas also communicate using body language. They show threats by flipping their upper lips back to show their teeth and gums. They also pull back their scalps to show their pale eyelids. A gelada shows it is giving up by running away or by presenting itself.

Conservation Status

In 2008, the IUCN said the gelada was of "Least Concern" for extinction. However, their population had dropped from an estimated 440,000 in the 1970s to about 200,000 in 2008. They are listed in Appendix II of CITES, which means their trade is controlled.

The biggest threats to geladas are that their living areas are shrinking because of farms growing larger. They are also sometimes shot because farmers see them as pests that eat their crops. In the past, these monkeys were caught to be used in labs or hunted for their capes to make clothes. As of 2008, there have been ideas to create new national parks and reserves to protect more geladas.

See also

In Spanish: Gelada para niños

In Spanish: Gelada para niños