Thomas Charles Hope facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Charles Hope

|

|

|---|---|

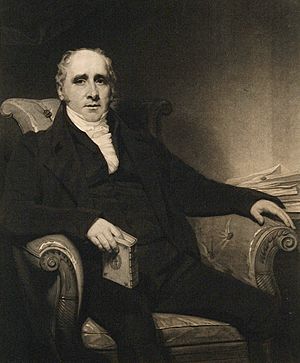

Thomas Charles Hope, Portrait by Henry Raeburn

|

|

| Born | 21 July 1766 Edinburgh, Scotland, Kingdom of Great Britain

|

| Died | 13 June 1844 (aged 77) Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

|

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh University of Paris |

| Known for | Maximum density of water (Hope's experiment) Discovery of strontium |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, medicine |

| Institutions | Lecturer in chemistry, University of Glasgow Professor of medicine and chemistry, University of Edinburgh President, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1815–1819) |

| Thesis | Tentamen inaugurale, quaedam de plantarum motibus et vita complectens (1787) |

| Doctoral advisor | Joseph Black |

Thomas Charles Hope (born July 21, 1766 – died June 13, 1844) was a Scottish doctor, chemist, and teacher. He is famous for two main things. First, he proved that a chemical element called strontium exists. Second, he created an experiment, now called Hope's Experiment, which shows that water is heaviest (has its maximum density) at 4 °C (39 °F).

Hope was also a leader in important scientific groups. He was the president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh from 1815 to 1819. He also served as vice-president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh from 1823 to 1833.

Interestingly, the famous scientist Charles Darwin was one of Hope's students. Darwin found Hope's chemistry lessons to be a highlight of his time at the university, which he otherwise found quite boring.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Charles Hope was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was the third son of Juliana Stevenson and John Hope, who was a surgeon and botanist. Thomas grew up in a place called High School Yards in the old part of Edinburgh.

He went to school right next door to his home at the High School. Later, he studied at the University of Edinburgh, where he earned his medical degree in 1787. He also studied at the University of Paris. At the University of Edinburgh, he learned from Professor Joseph Black, a well-known chemist. Hope was also the nephew of another doctor, Alexander Stevenson.

Discovering Strontium and Water's Density

In 1787, Hope became a chemistry teacher at the University of Glasgow. Two years later, in 1789, he became a professor of medicine there.

In 1791–1792, Hope did important experiments on a new chemical element. He suggested calling it "Stronities." He named it after Strontian, a village in Scotland where he found the mineral strontianite. This element was later renamed to Strontium. On November 4, 1793, Hope shared his discoveries with the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Hope also created the experiment that carries his name, Hope's Experiment. This experiment helped him figure out that water is densest at 4 °C (39 °F). This discovery also helped explain why icebergs float on water.

Teaching and Scientific Leadership in Edinburgh

In 1795, Professor Joseph Black chose Hope to be his assistant at the University of Edinburgh. Hope later took over Black's role as professor of medicine and chemistry in 1799, a position he held until 1843. Hope wanted to connect the study of medicine more closely with chemistry in his teaching.

Hope was very active in the scientific community.

- In 1788, he became a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He was also its vice-president from 1822 to 1833.

- From 1815 to 1819, he was the President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

- In May 1810, he became a member of the Royal Society of London.

Hope also supported education. In 1828, he gave £800 to start a chemistry prize at the University of Edinburgh. In the 1830s, he lived in a large house at 31 Moray Place in Edinburgh's New Town. He passed away at this home in 1844. He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in central Edinburgh.

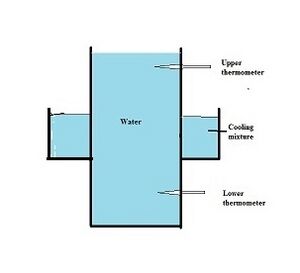

Hope's Apparatus: How it Works

Hope's apparatus is a special tool used to show how water's density changes with temperature. It has a tall container filled with water. Around the middle of this container, there's a section with cooling ice. Two thermometers are placed inside the water: one above the ice section and one below it.

Here's how it works:

- As the water in the middle cools down to 4 °C (39 °F), it becomes heavier (denser). This denser water sinks to the bottom of the container.

- The thermometer at the bottom will then show a steady temperature of 4 °C (39 °F).

- If the water cools even more, towards 0 °C (32 °F), it actually becomes less dense. This lighter water rises to the top of the container.

- The thermometer at the top will then show a steady temperature of 0 °C (32 °F).

This experiment clearly shows that water is densest at 4 °C (39 °F).