Thomas E. Watson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tom Watson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Senator from Georgia |

|

| In office March 4, 1921 – September 26, 1922 |

|

| Preceded by | M. Hoke Smith |

| Succeeded by | Rebecca Felton |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 10th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1891 – March 3, 1893 |

|

| Preceded by | George Barnes |

| Succeeded by | James C. C. Black |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Thomas Edward Watson

September 5, 1856 Thomson, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | September 26, 1922 (aged 66) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (Before 1892, 1920–1922) Populist (1892–1909) |

| Spouse | Georgia Durham |

| Education | Mercer University |

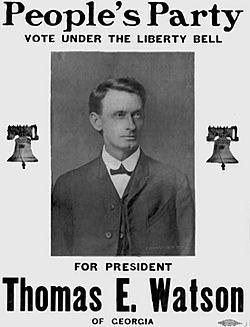

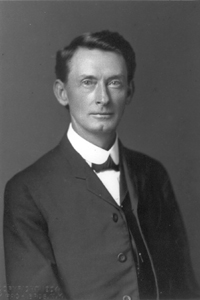

Thomas Edward Watson (born September 5, 1856 – died September 26, 1922) was an American politician, lawyer, newspaper editor, and writer from Georgia. In the 1890s, Watson became a champion for poor farmers. He was a key leader of the Populist Party.

He spoke out for farmers and criticized big businesses, bankers, and railroads. In 1896, he ran for Vice President with William Jennings Bryan on the Populist ticket. Watson was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1890. There, he helped create the law for Rural Free Delivery, which brings mail directly to homes in the countryside.

In the 1890s, Watson was seen as a leader who wanted poor white and Black people to work together. However, after 1900, his views changed. He began to express negative opinions about Black people and Catholics. Later, he also spoke against Jewish people. Two years before he died, he was elected to the United States Senate. He passed away while still serving in office.

Contents

Thomas Watson's Early Life and Career

Thomas E. Watson was born on September 5, 1856, in Thomson, Georgia. He came from an English family. He attended Mercer University for two years but had to leave because his family needed money.

After leaving college, he worked as a school teacher. In 1875, he became a lawyer. Watson joined the Democratic Party. In 1882, he was elected to the Georgia Legislature.

As a state lawmaker, Watson tried to stop powerful railroad companies from taking advantage of people. He proposed a bill to tax railroads, but it failed. This made Watson upset, and he left his position to go back to being a lawyer.

Watson as a U.S. Representative

Watson started to support the ideas of the Farmers' Alliance. In 1890, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He served in Congress from 1891 to 1893.

In Congress, Watson was one of the few Southern Democrats who joined the new People's Party. This party was also known as the Populist Party. The Populists wanted the government to own railroads, steamship lines, and telephone systems. They also supported ideas like a tax system where richer people pay more.

As a Populist, Watson tried to unite farmers of all backgrounds, including Black and white farmers. He also supported the right for Black men to vote.

Rural Free Mail Delivery

Even though Watson was part of a smaller group in Congress, he helped pass an important law. This law required the Post Office to deliver mail to farm families in remote areas. This service was called Rural Free Delivery (RFD).

Before RFD, people in the countryside had to travel far to pick up their mail. Sometimes they paid private carriers to deliver it. The new law changed this. Some people opposed RFD, like private carriers and small-town shop owners. They worried that people would visit towns less often if mail was delivered to their homes. They also worried about competition from mail-order companies like Sears, Roebuck and Company.

RFD officially started in 1896. It was a huge effort that took many years to set up across the country. It is still considered one of the biggest and most expensive projects ever done by the U.S. Postal Service.

Political Challenges and Publishing

Watson ran for re-election but lost his seat in 1893. During this time, other politicians in Georgia worked to make it harder for Black people and poor white people to vote. This was done to prevent groups like the Populists from gaining power.

After his defeat, Watson went back to being a lawyer in Thomson, Georgia. He also became an editor and business manager for the People's Party Paper, a newspaper published in Atlanta. His newspaper supported the idea of government by the people. It spoke out against class rule, powerful banks, and high taxes.

Vice Presidential Campaign

In the 1896 presidential election, leaders of the Populist Party talked with William Jennings Bryan, who was the Democratic Party's choice for president. The Populists believed Watson would be Bryan's running mate. However, after the Populist convention nominated Bryan, he announced that a more conservative banker named Arthur Sewall would be his Vice Presidential choice for the Democrats.

This caused a disagreement within the Populist Party. Some Populists refused to support Bryan. Watson's name still appeared on the ballot as Bryan's Vice Presidential nominee for the Populist Party. Watson received 217,000 votes for Vice President. Bryan's loss in the election weakened the Populist Party.

Changing Views and Later Campaigns

Watson had previously supported voting rights for Black people in Georgia and the South. However, after 1900, his views on this changed. He no longer believed the Populist movement should include all races. By 1908, Watson began to express negative and prejudiced views against Black people. He used his influential magazine and newspaper to spread these ideas.

Watson ran for president as the Populist Party candidate in 1904. He received 117,183 votes. In the 1908 election, his support dropped even further, with only 29,100 votes. After the 1908 campaign, the Populist Party ended.

Watson also became a strong critic of the Catholic Church. He believed that cities in the eastern U.S. were controlled by Catholics.

Later Years and World War I

Through his publications, Watson's Magazine and The Jeffersonian, Watson continued to have a lot of influence, especially in Georgia.

In 1913, Watson's newspaper played a role in stirring up public opinion during the case of Leo Frank. Frank was a factory manager accused of a crime. Watson's publications later began to spread very negative remarks about Jewish people. This was partly due to his strong dislike for his political rival, U.S. Senator Hoke Smith.

When World War I started in 1914, Watson was against the U.S. joining the war. He asked, "Do You Want Your Son Killed in Europe in A Quarrel You Have Nothing to Do With?". Because he opposed the war, the U.S. Post Office stopped delivering his publications. This caused his magazines and newspapers to close.

Election to Senate and Death

In 1918, Watson tried to run for Congress again but lost. He rejoined the Democratic Party. In 1920, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, defeating his rival Hoke Smith.

Thomas Watson died in 1922 at the age of 66 from a brain hemorrhage. Rebecca Latimer Felton was appointed to take his place. She served for only 24 hours, becoming the first female U.S. Senator.

Watson's Legacy

A part of U.S. Route 23 in Habersham County, Georgia is named the "Thomas E. Watson Highway" in his honor.

A 12-foot-high (3.7 m) bronze statue of Watson was placed on the lawn of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta. The statue had the words "A champion of right who never faltered in the cause." In 2013, the statue was moved to Park Plaza, across the street from the Capitol.

Works

- The Life and Speeches of Thos. E. Watson (1908)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas E. Watson para niños

In Spanish: Thomas E. Watson para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |