Farmers' Alliance facts for kids

The Farmers' Alliance was an important movement for farmers in the United States. It grew strong around 1875. This movement included different groups working together. There was the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union for white farmers in the South. The National Farmers' Alliance was for white and black farmers in the Midwest and High Plains. And the Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union was for African American farmers in the South.

One main goal was to help farmers escape the unfair "crop-lien system" after the American Civil War. The Alliance also wanted the government to control transportation. They supported an income tax to limit huge profits. They also wanted more money in circulation to make it easier for farmers to pay back loans. In the early 1890s, the Farmers' Alliance became involved in politics. They joined forces under the People's Party, also known as the "Populists."

Contents

Why Farmers Needed Help

Farming Troubles in the Midwest and Plains

Building the First Transcontinental Railroad across the U.S. was finished in 1869. After that, many more railway lines were built. The government and big railroad companies wanted to open up new areas for development. Instead of building railroads themselves, Congress gave money and land to private companies. About 129 million acres of public land went to these railway companies.

The railroads needed to sell this land to pay for their building costs. They had to attract new settlers to the lands west of the Missouri River. People used to think this land was bad for farming. But the railway companies spent millions of dollars advertising it. They said it was great for farming. After a financial crisis in 1873, many people were jobless. They looked for a new start. So, settlers rushed into the Midwest and Northern Great Plains.

Populations grew very fast. Kansas went from about 365,000 people to almost a million in the 1870s. Nebraska nearly tripled its population. Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakota Territory also saw big increases. Hundreds of new towns appeared. People started buying and selling farmland and city lots, creating an economic bubble. This growth continued into the 1880s.

However, the early 1880s had unusually rainy years. This made land prices high. But then, a long drought started in the summer of 1887. This ended the land boom. Crops failed, and land prices dropped sharply. Banks collapsed, and it became hard to get loans. A decade of tough times followed. Many communities were abandoned. Farmers who stayed felt very unhappy with the situation.

Farming Troubles in the Southern United States

The farming economy of the Southern United States was almost destroyed by the American Civil War. People who had invested in Confederate money lost everything. Those who owned African American slaves also lost their wealth. Large farms were broken up or couldn't be worked without free labor. So much land was sold that prices dropped, making it hard for landowners.

The South also faced huge costs to rebuild what the war destroyed. The financial system was too weak to give out enough loans. For example, in 1895, 123 counties in Georgia had no banks at all. Merchants took advantage of this. They charged very high prices and interest rates for goods.

A new farming system appeared after the war. Small farms became common. This was called the "share system" or "cropping system." People who didn't own land paid rent by giving a part of their crops to the landowner. In theory, this helped both landowners and poor farmers. Farmers would work harder to produce more. Landowners would get labor without paying cash wages.

But in reality, it became a system like slavery. Poor white and freed black farmers got trapped in debt to merchants and landowners. This was called the crop-lien system. Farmers mortgaged their future crops to get credit for things they needed now. These loans were legally binding. Farmers often had to pay very high prices and interest rates. If their debt was more than their crop's value, the arrangement rolled over to the next year. This created a never-ending cycle of servitude.

Also, this system made farmers grow only cotton. Merchants wanted cotton because it was easy to store and sell. This meant farmers couldn't grow enough food for themselves or their animals. This made them even more dependent on their merchant-creditors. Small farmers and tenant farmers in the South felt very unhappy.

How the Alliance Was Organized

The Northern Alliance

The National Farmers' Alliance, or "Northern Alliance," started on March 21, 1877. It was formed by members of the Grange movement from New York state. They wanted to fight unfair practices by railroads. They also wanted to change the tax system and legalize Grange-supported insurance companies.

This first group wasn't very effective. But it inspired a more successful Alliance group. This one was started on April 15, 1880, by newspaper editor Milton George in Chicago. George's newspaper, Western Rural, helped the new group become known. This led to many local groups being formed. It started in Filley, Nebraska and spread across the Midwest. In the beginning, members didn't pay dues. Editor George paid for the group's start, which helped it grow fast. Within a month, over 200 local groups were formed. By the end of the first year, they claimed 1,000 local groups.

The Northern Alliance grew fastest in areas hit by drought in 1881. These included Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Minnesota. Growth was slower in states like Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Local groups were easier to start than statewide ones. In its early years, local groups were most important. But state-level groups did form. Delegates met in Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, and Michigan between 1881 and 1882.

The Alliance wanted to protect farmers from big businesses and monopolies. These included railroads and unfair public officials. The Northern Alliance pushed for fairer taxes on mortgaged property. They wanted an income tax law. They also wanted to stop public officials from getting free travel passes. And they wanted Congress to control trade between states.

By October 1881, the Alliance claimed 24,500 members. A year later, in October 1882, they claimed 2,000 local groups and 100,000 members. This was their peak. But then, farming became more prosperous in the Midwest in 1883. People lost interest. The 1884 convention had few attendees, and no convention was held in 1884. Farmers had work and money, so their interest in the reform group dropped. Even Milton George published less news about the Alliance. State and local groups became inactive.

But then, wheat and livestock prices fell after the 1884 harvest. This made the Farmers' Alliance active again. In 1885, a new Alliance group started in the Dakota Territory, where wheat was very important. Then a state organization formed in Colorado. Interest spread westward. New national rules were written and sent to all readers of Western Rural. A successful convention was held in November 1886. A system of dues was started. This helped fund and energize the state organizations.

The group's goals became more radical. They demanded government ownership of some major railroad lines. They also wanted unlimited coinage of silver at its old ratio to gold. They started working with the Knights of Labor. This was a leading industrial trade union at the time. By 1890, ten state organizations were fully working. New members joined the Farmers' Alliance at a rate of 1,000 per week. Kansas alone had 130,000 members. Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Minnesota were close behind. The national office hoped for 2 million members soon.

The idea came up to use this growing membership to achieve their goals through politics.

The Southern Alliance

The National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, or "Southern Alliance," started around 1875. A group of ranchers in Lampasas County, Texas formed a Texas Alliance. They worked together to catch horse thieves and find lost animals. They also bought large amounts of supplies together. This group slowly started to do more. They responded to unfair actions by land speculators and big cattle companies. The group grew and became statewide in 1878. But it almost ended when it tried to get into politics. It split because of groups supporting the Democratic and Greenback parties.

In 1879, the Northern Alliance influenced Parker County, Texas. A new group started there, led by a former member of the Lampasas County Alliance. This new group followed the Northern Alliance's rules. It also stayed out of party politics. Soon, a dozen local groups were formed based on this model. This Texas group became a legal business in 1880. It was called the "Farmers' State Alliance." It then spread across Central and Northern parts of the state. It also went into the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). By the end of 1885, this growing group claimed about 50,000 members. They were spread among more than 1200 local groups, called "Sub-Alliances."

In the early 1880s, this Texas Farmers' State Alliance was seen as part of the Northern Alliance. But the national group didn't collect dues then. So, the connection was more an idea than real. When the Northern Alliance started collecting dues, the Texas group had to decide its official connection.

Charles W. Macune, whose father was a Methodist preacher, became the leader of this Texas group. He was elected Chairman of the Executive Committee in 1886. Macune quickly stopped a split in the group. Some members wanted to start an independent political party. He then united the group. He wanted them to be independent from the Northern Alliance. He also wanted them to expand actively. First, Macune arranged a merger with the Louisiana Farmers' Union. This group started in 1880 and became a secret society in 1885. The groups joined under a new name: the National Farmers' Alliance and Cooperative Union of America.

This was an early step in uniting farmers across the American cotton belt. The Southern Alliance wanted similar things as the Northern Alliance. They pushed for an end to national banks and monopolies. They wanted free coinage of silver. They also wanted the government to print paper money (Greenback or Fiat money). They asked for loans on land, special government warehouses, income tax laws, and changes to tariffs.

In 1889, the National Farmers' Alliance and Cooperative Union joined with a large rival group. This group was called the Agricultural Wheel. They formed a new group called the National Farmers' and Laborers' Union of America. Talks began to unite this larger Southern Alliance with the Northern Alliance. A merger would have created a bigger, stronger group. But unity failed because of disagreements. These included how the leaders would be chosen. There were also different views on allowing non-white members. And Southern and Northern farmers had different economic interests, leading to program disagreements.

At its December 1889 meeting in St. Louis, the National Farmers' and Laborers' Union of America changed its name again. This time, it became the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union. This was the name it kept for the rest of its existence.

The Colored Alliance

The Southern Farmers' Alliance did not allow black farmers to join. J.H. Turner, a leader of the Alliance, said that former slave-owners had given black farmers "the best advice." He also said they had protected them in business. This view was common among Southern whites at the time. It did not help black farmers feel that their concerns were shared. Since they were banned from the Southern Farmers' Alliance due to racism, African-American farmers had to start their own group.

In December 1886, a group of black farmers formed the Alliance of Colored Farmers of Texas. This was the start of the Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union. It was also known as the "Colored Farmers' Alliance." They created a set of rules. The new group would be a mutual aid society. It would focus on education and improving farming methods. It would also raise money to help sick or disabled members and their families. The group started as a secret society.

In February 1887, the group became a legal business in Texas. It was called the Alliance of Colored Farmers. Then, a meeting was held in Lovelady, Texas on March 14, 1888. There, the group decided to become a national organization. Its new name was the Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union. The group also started its own newspaper, called The National Alliance.

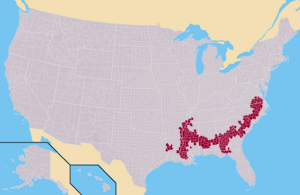

The organization quickly spread across the American South. It had a presence in every Southern state.

The Colored Farmers' Alliance opened cooperative stores. Members could buy needed goods at lower prices there. They also published newspapers to teach members new farming techniques. In some places, they raised money to support the underfunded, segregated black schools.

The Colored Farmers' Alliance was strongest in 1891. It claimed about 1.2 million members.

Who Opposed the Alliance

A group called the Knights of Reciprocity opposed the Alliance. It was founded in Garden City, Kansas in the winter of 1890. It was started by Republicans like Jesse Taylor, D. M. Frost, and S. R. Peters. By 1895, the Knights claimed 125,000 members. They had groups in Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Ohio. Their founders included Masons, Oddfellows, and Pythians. Their goals included fair trade, protecting American industries, and pensions for Union veterans. They also wanted to stop people who took or offered bribes for votes from voting.

The Knights strongly opposed the political alliance between the Democratic Union Labor and Farmers Alliance. A paper from them in 1891 said:

The only way for the farmers to meet the Alliance secret political society is with a secret society the object of which shall not be to nominate men for office, but to assist in educating the people and making them thoroughly acquainted with the wants of all the people and the fallacies of the Alliance "calamity" howlers, who are traveling from State to State, county to county, town to town, township to township, schoolhouse to schoolhouse, not for the good of the people, but for the money they make and in hopes of political promotion. The people should organize at once in opposition to this gigantic scheme.

What the Alliance Wanted and Achieved

The Farmers' Alliance was a large movement with three separate parts. It existed for over two decades. So, it's hard to list just a few goals for the whole group. As Southern Alliance leader C.W. Macune said in 1891, the group's goals changed. They responded to local problems and conditions:

No man ... can give a perfect definition of the purposes of the Farmers' Alliance; and he who attempts a definition simply gives his own personal conception of the subject, which may be more or less valuable, according to whether his field of observation and his accuracy of judgment are good or otherwise.

In a broad sense, the purposes of the Farmers' Alliance ... cover today a remedy for every evil known to exist and afflict farmers and other producers, and in the future should cover every contingency that may arise, presenting evil to be combatted by means of organization; they are accumulative and ever changing, as the enemy assumes a new guise.

Some of their main concerns were unfair credit terms and not enough money in circulation. They also worried about huge profits taken by merchants and middlemen. They felt railroads charged small farmers too much. And they were concerned about land prices being affected by speculation.

The Farmers' Alliance had many achievements. For example, many Alliance groups set up their own cooperative stores. These stores bought goods directly from big sellers. Then they sold them to farmers at lower prices, sometimes 20 to 30 percent less than regular stores. But these stores had limited success. Wholesale merchants often fought back. They would temporarily lower their prices to drive the Alliance stores out of business.

The Farmer's Alliance also built its own mills for flour, cottonseed oil, and corn. This helped farmers who didn't have much cash. They could process their goods at a lower cost. This made it cheaper to sell their products.

The National Goals

Local Alliance policies didn't fully solve the big problems. These included falling prices and not enough money. By 1886, there were disagreements within the movement. Some wanted a national political agenda. Others wanted only local economic actions. In Texas, this split became clear in August 1886. This was at the statewide meeting in Cleburne. The political activists won. They passed a list of political demands. These included supporting the Knights of Labor and a big railroad strike in 1886. Other demands included changes in government land policy and railroad regulation. They also demanded using silver as legal tender. They believed this would increase the money supply. This would help with falling prices and lack of credit.

The Alliance wanted to change how Americans worked. They pushed for an eight-hour workday. They wanted to get rid of national banks. This would allow private, local banks to form. The Alliance wanted an income tax. They also wanted the freedom to print their own money. And they wanted to borrow money from the government to buy land. The Alliance also tried to stop foreign companies from owning land in America. They wanted to directly elect federal judges and senators. The Alliance gained strong political power. They controlled elections in states in the South and the West.

In the South, the main demands were for government control of transportation and communication. This was to break the power of big company monopolies. From 1890, they also demanded a national "Sub-Treasury Plan." This plan called for government-owned warehouses. Farmers could store non-perishable crops there at low cost. Farmers could then get low-interest loans. These loans would be up to 80% of the stored goods' value. They would be paid in U.S. Treasury notes. The Democratic Party did not support this plan. This led the Farmers' Alliance to get directly involved in politics. They formed their own group, the People's Party.

The Southern Alliance also wanted reforms for currency, land ownership, and income tax. Meanwhile, the Northern Alliance strongly pushed for free coinage of large amounts of silver.

Political activists also tried to unite the two Alliance groups. They wanted to include the Knights of Labor and the Colored Farmers' National Alliance. But these efforts to unite failed.

Becoming the Populist Movement

As an economic movement, the Alliance had limited and short-term success. Cotton brokers used to deal with individual farmers for small amounts of cotton. Now, they had to deal with Alliance members for much larger sales. But this unity often didn't last. Commodity brokers and railroads fought back. They boycotted the Alliance. Eventually, this broke the movement's power. The Alliance had never run its own political candidates. It preferred to work through the existing Republican Party in the Midwest and Democratic Party in the South. But these parties often didn't fully support the Alliance's goals.

The Alliance failed as an economic movement. But historians see it as creating a "movement culture" among poor rural people. This failure led the Alliance to become a political movement. They started running their own candidates in national elections. In 1889–1890, the Alliance was reborn as the People's Party, or "Populists." This new party included both Alliance members and Knights of Labor members. The Populists ran national candidates in the 1892 election. Their platform basically repeated all the demands of the Alliance.

Elected Officials From the Alliance

- John Rankin Rogers, two-term Washington State Governor (1897–1901).

- Marion Butler, one-term U.S. Senator from North Carolina (1895–1901).

Newspapers of the Alliance

- American Nonconformist, Tabor, Iowa. Edited by Henry Vincent.

- Alliance Vindicator, Texas. Edited by James H. Davis.

- Kansas Farmer, Topeka, Kansas. Edited by William A. Peffer.

- National Alliance, Houston, Texas. —No copies known to have survived.

- National Economist, Washington, D.C.. Edited by Charles William Macune.

- Progressive Farmer, Raleigh, North Carolina. Edited by Leonidas LaFayette Polk.

- Southern Mercury, Dallas, Texas. Edited by Harry Tracy.

- Western Rural and Family Farm Paper, Chicago, Illinois. Edited by Milton George.

See also

In Spanish: Farmers' Alliance para niños

In Spanish: Farmers' Alliance para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |