Tracklaying race of 1869 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ten Mile Day |

|

|---|---|

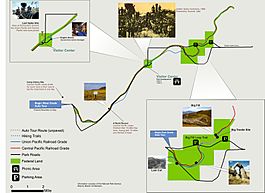

Map of Golden Spike National Historical Park, showing where the record-setting 10 miles of track were laid.

|

|

| Overview | |

| Owner | Central Pacific Railroad |

| Service | |

| System | First Transcontinental Railroad |

| History | |

| Opened | 28 April 1869 |

| Closed | 1 January 1905 |

| Technical | |

| Track length | 10.01 mi (16.11 km) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

The Ten Mile Day refers to an amazing feat in railroad history. On April 28, 1869, workers for the Central Pacific Railroad laid more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) of track in a single day. This was a world record at the time!

This incredible effort happened during the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the United States. Two companies, the Central Pacific (CP) and the Union Pacific (UP), were racing to connect the East and West coasts. They competed to see who could lay the most track each day.

The record set by the Central Pacific's Chinese and Irish crews was a huge moment. It showed how fast and efficiently they could work. This event is a famous part of American history, highlighting the hard work that built the nation's first cross-country railway.

Contents

Building the Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a massive project. It aimed to connect the eastern and western parts of the United States by rail. This would make travel and trade much faster and easier.

Why Did Railroads Race?

In 1866, a law called the Pacific Railway Act was changed. It allowed the Central Pacific to build east and the Union Pacific to build west. The two lines would meet somewhere in the middle.

The government offered land and money to each railroad. The more miles of track a company laid, the more land and money it received. This created a strong competition between the Central Pacific and Union Pacific. Each company wanted to lay as much track as possible.

How Did They Build the Tracks?

Building a railroad involved several steps. First, engineers had to survey the best route. Then, crews would grade the land, making it level for the tracks. This was called the "roadbed."

The Central Pacific faced tough challenges. Their route went through the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains. This meant a lot of grading work, which slowed them down. For the first five years, they spent most of their time grading, not laying tracks.

Old vs. New Tracklaying Methods

The Central Pacific first used a slower method for laying tracks. A special car carried rails, ties, and spikes to the end of the line. Workers would unload one pair of rails, lay them, and then the car would move forward. This method was slow because only a few workers could work at once.

The Union Pacific, however, developed a faster method. Their crews were organized like an assembly line. Each worker had a specific job, like handling rails, spiking, or connecting sections. This allowed many more men to work at the same time. The tracklaying car could also move over loose rails before they were fully spiked. This meant work could happen along a longer section of track at once.

This new method allowed the Union Pacific to lay tracks much faster. They could lay up to 3 miles (4.8 km) of track per day. This speed impressed the Central Pacific.

The Race to Set Records

The competition between the two railroads was intense. Both companies wanted to set new records for tracklaying.

Breaking Daily Tracklaying Records

In August 1868, Union Pacific crews laid 4.5 miles (7.2 km) of track in one day. This made Charles Crocker, the head of the Central Pacific, very competitive. He told his superintendent, James Harvey Strobridge, to beat that record.

Central Pacific crews responded quickly. On August 19, they laid just over 6 miles (9.7 km) of track. But the Union Pacific fought back. On October 26, they laid an amazing 8 miles (12.9 km) of track in a single day! They worked from 3 AM until midnight to achieve this.

The Central Pacific soon adopted the Union Pacific's faster methods. By March 1869, they were regularly laying 4 miles (6.4 km) of track per day. This set the stage for the famous Ten Mile Day.

The Ten Mile Day: April 28, 1869

As the two railroads got closer to their meeting point at Promontory, Utah, the Union Pacific's progress slowed. They had very difficult terrain ahead. The Central Pacific was only 14 miles (22.5 km) from finishing their section. The Union Pacific was 8 miles (12.9 km) from Promontory.

There was a rumored bet between the vice-president of Union Pacific, Thomas C. Durant, and Charles Crocker of the Central Pacific. The bet was supposedly for $10,000 to see whose crew could lay the most track in a day. However, there's no clear proof this bet actually happened.

The Central Pacific's first attempt at a record on April 27 failed when a train went off the tracks. They only laid 2 miles (3.2 km) that day.

A Day of Hard Work and Triumph

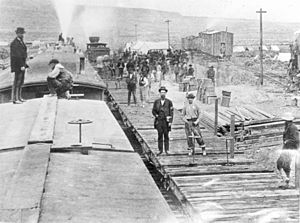

The next day, April 28, 1869, work began at sunrise. Teams of horses pulled railcars loaded with supplies to the end of the track. Each car carried 8 pairs of 30-foot (9.1 m) rails, along with spikes and other materials.

As a loaded car reached the end, a team of four rail handlers quickly pulled off a pair of rails. They laid them over the wooden ties. The car then moved forward over the loose rails. Another team of workers started spiking the rails in place. More teams finished the spiking and buried the ends of the ties.

The work was incredibly fast. One reporter timed how quickly two carloads of track were laid. Each car, holding 240 feet (73 m) of track, was emptied in just 80 seconds, then 75 seconds!

By lunchtime, around noon, the crews had already laid 6 miles (9.7 km) of track. They took an hour-long break to eat. They even named their lunch spot "Camp Victory."

After lunch, they spent an hour bending rails for a curving uphill section. The same eight-man team that laid rails all morning kept working. When they stopped at 7 PM that night, the Central Pacific crews had laid an amazing 10 miles and 56 feet (16.1 km) of track! This set a new world record.

To prove the track was strong, a locomotive was run over the newly laid section. It completed the route in just 40 minutes. The Central Pacific finished their part of the line to Promontory Summit the very next day.

On this record-setting day, workers used:

- 25,800 wooden ties

- 3,520 rails (each weighing about 560 pounds or 254 kg)

- 55,000 spikes

- 14,080 bolts

This amounted to over 4.4 million pounds (2 million kg) of materials!

Union Pacific representatives were invited to watch the record attempt. After the first day's failure, they were doubtful. But by the end of the Ten Mile Day, one delegate admitted that the Central Pacific's organization was "far superior."

The names of the eight Irish rail-layers and two track gaugers were recorded. The many Chinese workers also played a huge role, though their specific tasks were not as detailed in records. The Chinese and Irish crews of the Central Pacific worked well together.

Lasting Impact

Even though the Central Pacific set a new record, it was later broken. Some Union Pacific workers who couldn't break the CP record later worked for the Kansas Pacific Railway. On August 15, 1870, Kansas Pacific crews laid 10 miles and 1,320 feet (16.5 km) of track in a single day. This was done by two crews working from opposite ends. This completed the second continuous transcontinental railroad.

Despite this new record, the Southern Pacific (which took over the Central Pacific) continued to claim the 1869 record for many years.

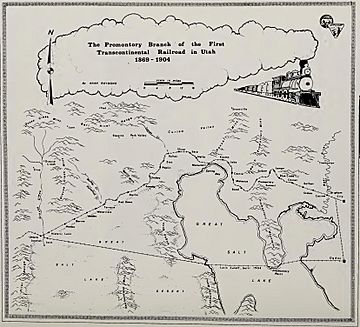

The 10-mile section of track laid in 1869 was part of the original route. In 1903, a new, shorter route called the Lucin Cutoff was built. This bypassed the original section. The old rails were eventually removed in 1942 to be reused during World War II.

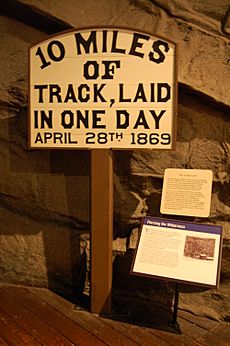

Today, at the Golden Spike National Historical Park, visitors can see a replica of the sign that marked the 10-mile record. The original sign is believed to be in the Utah State Capitol building. Another replica is displayed at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

The Ten Mile Day in Art and Books

The Ten Mile Day has inspired many creative works:

- Author Frank Chin's 1991 novel Donald Duk features the protagonist dreaming about the events of that day. He feels frustrated that only the Irish tracklayers' names were recorded, not the Chinese workers.

- Mary Ann Fraser wrote and illustrated the children's book Ten Mile Day in 1993. It tells the story of April 28, 1869, for young readers.

- Artist Mian Situ created a painting called Ten Miles in One Day, Victory Camp, Utah, April 28, 1869. It was sold at the Autry Center in 2007.