High Court of Justice (1649) facts for kids

The High Court of Justice was a special court created by the Rump Parliament. Its job was to put King Charles I on trial. Even though this court was made just for the King's trial, its name was later used for other courts by the government.

Contents

Why the Court Was Needed

The English Civil War had been going on for almost ten years. After the first part of the war, many people in Parliament thought the King had reasons for fighting. They believed he could still be King, but with less power.

However, King Charles started a second war while he was already defeated and held captive. This made many people very angry. They blamed him for causing more bloodshed. A secret deal he made with the Scots, called the "Engagement" treaty, was seen as a huge betrayal. Oliver Cromwell said it was "a more terrible treason" than anything before. Cromwell, who had supported talking with the King, now refused to negotiate further.

The King's wars caused thousands of deaths. It's thought that about 85,000 people died directly from fighting in the first two civil wars. Another 100,000 might have died from war-related diseases. This was a huge number of deaths for England at the time.

After the second war, the New Model Army and a group in Parliament called the Independents wanted the King to be punished. But they weren't the majority in Parliament. Many members, mainly Presbyterians, still wanted to negotiate with Charles and keep him as King.

The army was very upset that Parliament was still considering Charles as King. So, soldiers from the New Model Army marched to Parliament. On December 6, 1648, they removed many members from the House of Commons. This event is known as "Pride's Purge" after Colonel Thomas Pride, who led the operation. His soldiers stood at the entrance, checking a list. They arrested 45 Members of Parliament (MPs) and stopped 146 others from entering.

Only about 75 MPs were allowed inside, and only if the army approved. On December 13, the "Rump Parliament" (as this smaller group was called) stopped all talks with the King. Two days later, the army's leaders decided the King should be moved to Windsor. They wanted to bring him to justice quickly. In mid-December, the King was moved from Windsor to London.

Kings and Parliament in the Past

It wasn't completely new for Parliament to be involved in ending a king's rule or even trying a monarch. In the past, Parliament had asked two kings, Edward II (in 1327) and Richard II (in 1399), to give up their thrones. However, in those cases, Parliament was usually doing what a new king wanted.

There was also the case of Lady Jane Grey. Parliament said she was not the rightful queen. She was later put on trial, found guilty, and executed for serious crimes against the country. But she was not on trial while she was still ruling as queen.

Setting Up the Court

After the King was brought to London, the Rump Parliament passed a new law. This law created the High Court of Justice to try Charles I for serious crimes against the people of England. The law first named 3 judges and 150 other people to be part of the court. But the House of Lords disagreed, so the judges and members of the Lords were removed.

When the trial began, there were 135 people chosen to try the King. However, only 68 of them actually sat as judges. John Cook, a lawyer, was chosen to present the case against the King.

Charles was accused of acting against England. The charge said he used his power for his own benefit, not for the good of the country. It stated that he "treacherously and maliciously started a war against Parliament and the people." It also said his actions were meant to gain "personal power" for himself and his family, instead of protecting "public interest, common rights, liberty, justice, and peace." The accusation claimed he was "guilty of all the serious crimes, deaths, and damage" caused by the wars.

The House of Lords refused to approve the new law, and the King certainly didn't approve it. But the Rump Parliament called it an "Act" and went ahead with the trial anyway. On January 6, they voted again, 29 to 26, to confirm their plan to try the King. At this time, the number of people on the court was reduced to 135. Any twenty of them could make decisions. Judges, members of the House of Lords, and others who might support the King were removed.

The court members met on January 8 to plan the trial. Less than half of them were there, which happened often. On January 10, John Bradshaw was chosen to lead the court. Over the next ten days, they finished planning. They decided on the final accusations and gathered the evidence.

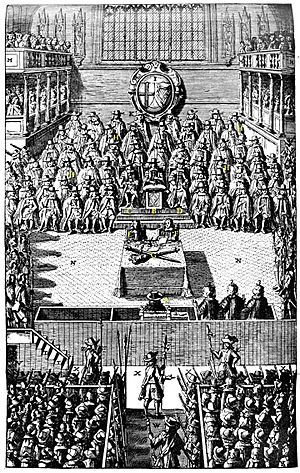

The Trial

The trial started on January 20, 1649, in Westminster Hall. It began with a dramatic moment. After the trial was officially open, the lawyer John Cook stood up to read the accusations. He stood next to the King and began to speak. But Charles tried to stop him by tapping him sharply on the shoulder with his cane and telling him to "Hold." Cook ignored him and kept speaking. Charles poked him a second time and tried to speak himself. Cook still continued. Charles, very angry, hit Cook's shoulder so hard that the fancy silver tip of his cane broke off. It rolled down Cook's robe and clattered onto the floor between them. No one would pick it up, so Charles had to bend down to get it himself.

When Charles was given a chance to speak, he refused to say if he was guilty or not guilty. He argued that no court had the right to judge a king. He believed his power to rule came from God and from England's traditions and laws. He felt that those trying him were only acting with military force. Charles insisted the trial was illegal. He said, "No smart lawyer will say that a king can be accused... one of their rules is, that the King can do no wrong." Charles asked, "By what power am I called here? By what lawful authority?" He argued that the House of Commons alone could not try anyone. So, he refused to enter a plea. The court disagreed, saying that "the King of England was not a person, but an office." They believed the King was given limited power to rule "by and according to the laws of the land and not otherwise."

The court decided to act as if the King had pleaded guilty. They did not use the harsh method of pressing him with stones, which was sometimes done if someone refused to plead. However, they did listen to witnesses to help the judges make their decision. Thirty witnesses were called, but some were later excused. The evidence was heard in a different room, not in Westminster Hall. King Charles was not there to hear the evidence against him, and he could not question the witnesses.

The King was found guilty at a public meeting on Saturday, January 27, 1649. He was sentenced to death. His sentence said: "The court is sure that Charles Stuart is guilty of the crimes he was accused of. Therefore, they judge him a tyrant, a traitor, a murderer, and a public enemy to the good people of the nation. He is to be put to death by cutting off his head from his body." To show they agreed, all 67 court members present stood up. For the rest of that day and the next, people signed his death warrant. Finally, 59 of the court members signed it, including two who weren't there when the sentence was passed.

Execution

King Charles was beheaded in front of the Banqueting House at the Palace of Whitehall on January 30, 1649. He said that he wanted the freedom of the people as much as anyone. But he also said:

I must tell you that their freedom comes from having government. ... It is not about them having a share in the government; that is not for them. A subject and a sovereign are completely different things.

Francis Allen handled the payments and records for the execution.

What Happened Next

After Charles I was executed, there was more fighting in Ireland, Scotland, and England. This is known as the Third English Civil War. About a year and a half after the execution, Prince Charles was declared King Charles II by the Scots. He led an invasion of England but was defeated at the Battle of Worcester. This battle marked the end of the civil wars.

The High Court of Justice Later On

The name "High Court of Justice" continued to be used during the time when England had no king (called the Interregnum). For example, James Earl of Cambridge was tried and executed by a "High Court of Justice" on March 9, 1649.

In the years that followed, new laws were passed to set up more High Courts of Justice. These laws were later cancelled when the King returned, because they had not been approved by a king.

- March 26, 1650: A law to create a High Court of Justice.

- August 27, 1650: A law giving more power to the High Court of Justice.

- December 10, 1650: A law to create a High Court of Justice in certain counties.

- November 21, 1653: A law to create a High Court of Justice.

On June 30, 1654, John Gerard and Peter Vowell were tried for serious crimes against the country by the High Court of Justice. They had planned to kill the leader, Oliver Cromwell, and bring Charles II back as king. The plotters were found guilty and executed.

The King Returns and Beyond

After the King returned in 1660, everyone who had been part of the court that tried and sentenced Charles I was targeted by the new king. Most of those who were still alive tried to escape the country. Many fled to Europe, while some were hidden by leaders in the New Haven Colony in America. Except for Richard Ingoldsby, who regretted his actions and was pardoned, all those who were caught were executed or put in prison for life.

The accusations made against King Charles I were similar to those made by the American colonists against George III a century later. They also said that the king was "trusted with limited power to govern by the laws of the land, and not otherwise." They claimed he used his power to "rule according to his will" and "overthrow the rights and liberties of the people."

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |