Tsilhqotʼin facts for kids

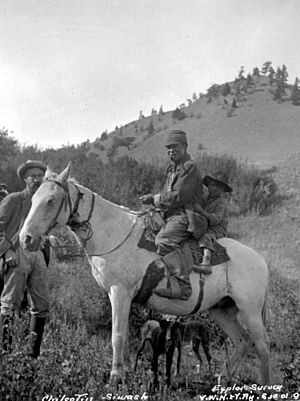

Tsilhqotʼin man on horse (1901)

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4,100 (2008) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (British Columbia) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Tsilhqotʼin | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dakelh, Navajo |

The Tsilhqotʼin (say: chil-KOH-tin) are an Indigenous group of people in British Columbia, Canada. Their name means "People of the river." They speak a language called Tsilhqotʼin, which is part of the Athabaskan language family. They are the most southern Athabaskan-speaking Indigenous people in British Columbia.

In 2014, the Tsilhqotʼin Nation won an important court case. This case confirmed their rights to their traditional lands. It also meant that the government must talk to them before using their lands for things like mining.

Contents

A Look at Tsilhqotʼin History

Life Before Europeans Arrived

Before Europeans came, the Tsilhqotʼin Nation was very strong. They were known as a warrior nation. They had influence over a large area, from the Similkameen region to the Rocky Mountains.

The Tsilhqotʼin were part of a big trade network. They controlled the trade of obsidian. Obsidian is a type of volcanic glass. It was used to make tools like arrowheads.

Early European Trade

The Tsilhqotʼin first saw European goods in the late 1700s. British and American ships came to the coast to trade for animal furs. By 1808, a fur-trading company set up posts north of the Tsilhqotʼin territory. They traded directly or through other Indigenous groups.

In 1821, the Hudson's Bay Company built a fur trade post called Fort Alexandria. This fort was on the Fraser River. It became the main place for the Tsilhqotʼin to get European goods.

Impact of New Diseases

When Europeans and other Indigenous groups met, new diseases spread. Europeans had been exposed to these diseases for a long time. This meant they had some protection. But Indigenous peoples had no protection. Many people became very sick and died.

Some of the diseases that caused many deaths among the Tsilhqotʼin were:

- Whooping cough in 1845

- Measles in 1850

- Smallpox in 1855 and again in 1862–1863

The smallpox epidemic of 1862–1863 was especially bad. It greatly reduced the number of Indigenous people in British Columbia. Some groups were almost completely wiped out. The Tsilhqotʼin were somewhat protected because they lived in an isolated area. But their oral histories still tell of the many deaths from these diseases.

Gold Rush and New Settlers

In the 1860s, people started looking for gold along the Fraser River. Many miners came to the area. Businesses and merchants followed them. Farmers and ranchers also came to provide food for the mining towns.

This led to competition for land and resources. The Tsilhqotʼin and the new settlers often disagreed. These disagreements led to a series of events known as the Chilcotin War.

Changes to Land and Rights

Early governors supported setting aside land for Indigenous peoples. This land was called a reserve. They also wanted Indigenous people to learn farming. But later, a new commissioner changed this policy. He said Indigenous peoples had no rights to the land.

By 1866, Indigenous peoples in British Columbia had to ask permission to use their own lands. Newspapers supported settlers taking Indigenous lands. Sometimes, settlers even plowed over Indigenous burial grounds. Indigenous peoples who tried to get help from the law were refused.

Challenges with the Environment

In the 1870s, the Tsilhqotʼin lost much of their hunting land. The number of salmon runs also went down. This made them rely more on farming. They started growing grains and vegetables. They also built irrigation ditches and raised animals.

However, settlers claimed water rights. This made farming even harder for Indigenous peoples. They were forced to live on very small pieces of land. For example, 150 Indigenous people lived on only 20 acres in Canoe Creek. Many faced the threat of starvation.

Residential Schools and Their Impact

Catholic missionaries were sent to convert Indigenous children to Christianity. In 1891, the first group of children was sent to a "formal" school. This was part of the Canadian Indian residential school system. This program continued for about 60 years.

Children were often taken from their homes to attend St. Joseph's Mission School. Some parents tried to hide their children to keep them safe. Children sometimes ran away from the schools. Within the first 30 years, there were investigations into physical abuse and poor nutrition at these schools. The mission school finally closed around 1981.

Voting Rights

Indigenous peoples were not allowed to vote in Canadian federal elections until 1960. They could not vote in provincial elections until 1949.

Tsilhqotʼin Communities Today

Today, about 5,000 Tsilhqotʼin people live in British Columbia. They live in and around Alexandria and Williams Lake. Many communities are along Highway 20.

Here are some of the Tsilhqotʼin First Nations communities:

- Toosey First Nation (Tlʼesqox of the Tsilhqotʼin) (near Riske Creek)

- Yunesitʼin First Nation (Stone First Nation) (near Hanceville)

- Tlʼetinqox-tʼin Government Office (Anaham Reserve First Nations) (east of Alexis Creek)

- Tŝideldel First Nation (Alexis Creek First Nation) (at Redstone)

- Ulkatcho First Nation (at Anahim Lake; this community also includes some Dakelh and Nuxalk people)

- ʔEsdilagh First Nation (Alexandria First Nation) (near Alexandria)

- Xeni Gwetʼin First Nation (in the Nemaia Valley)

Besides these Indigenous communities, there are only two small towns in the area: Alexis Creek and Anahim Lake. The Tsilhqotʼin people are still the largest group in the Chilcotin plateau.

Tsilhqotʼin First Nations belong to two main groups called tribal councils:

- Carrier-Chilcotin Tribal Council (includes Toosey First Nation and Ulkatcho First Nation, along with other groups)

- Tsilhqotʼin National Government (includes ʔEsdilagh, Tŝideldel, Yunesitʼin, Tlʼetinqox-tʼin, Xeni Gwetʼin, and Toosey First Nation)

The Tsilhqotʼin region is known for its beautiful nature. It has rolling grasslands, large forests of lodgepole pine and Douglas fir trees. There are also many lakes, rivers, and ponds. The area has volcanic landforms and snow-covered mountains. Highway 20 runs through this land, connecting Williams Lake to Bella Coola.

See also

- Tsilhqotʼin language

- Chilcotin War

- Carrier Chilcotin Tribal Council

- Tsilhqotʼin Tribal Council

- Tsilhqotʼin Nation v. British Columbia

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |