United States Foreign Service facts for kids

The flag of a U.S. Foreign Service Officer

|

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1924 |

| Employees | 13,770 |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent department | Department of State |

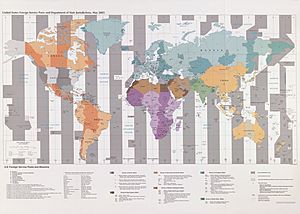

| Map | |

Map of U.S. Foreign Service posts (2003)

|

|

The United States Foreign Service is a group of over 13,000 skilled professionals. They work for the United States Department of State and other U.S. government agencies. Their main job is to carry out America's foreign policy and help U.S. citizens living or traveling overseas. The current leader is Carol Z. Perez.

The Foreign Service was created in 1924 by the Rogers Act. This law brought together all the different U.S. government groups that handled foreign relations. It combined consular (helping citizens and trade) and diplomatic (representing the country) services into one team. The Rogers Act also allowed the United States Secretary of State to send diplomats to work in other countries.

Members of the Foreign Service are chosen through special written and spoken tests. They work at 265 U.S. diplomatic offices around the world. These include embassies, consulates, and other facilities. Foreign Service members also work at the main offices of four foreign affairs agencies in Washington, D.C.. These are the Department of State, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Commerce, and the United States Agency for International Development.

The Foreign Service is led by a Director General. The President of the United States chooses this person, and the Senate must agree. Usually, the Director General is someone who has worked as a Foreign Service Officer before. This position was created by Congress in 1946.

Contents

- A Look Back: How the Foreign Service Began

- The Rogers Act: Uniting Services

- The Foreign Service Act of 1946

- The Foreign Service Act of 1980

- Who Are Foreign Service Members?

- Agencies in the Foreign Service

- How Big is the Foreign Service?

- How to Join the Foreign Service

- Life as a Foreign Service Member

- Challenges: "Clientitis"

- Foreign Service Career System

A Look Back: How the Foreign Service Began

On September 15, 1789, the first U.S. Congress created the Department of State. At first, there were two separate groups for foreign work. The Diplomatic Service sent ambassadors to represent the U.S. in other countries. The Consular Service sent consuls to help American sailors and promote international trade.

For many years, ambassadors and consuls were chosen by the president. Until 1856, they didn't even get a salary! They often had their own businesses and made money that way. In 1856, Congress started paying salaries to some consuls. Those who got a salary could not do private business.

First Woman in the Foreign Service

Lucile Atcherson Curtis was a trailblazer. She was the first woman to be appointed as a U.S. Diplomatic or Consular Officer in 1923. The unified Foreign Service was officially created in 1924. At that time, Diplomatic and Consular Officers became Foreign Service Officers.

The Rogers Act: Uniting Services

The Rogers Act of 1924 was a big step. It combined the diplomatic and consular services into one Foreign Service. This law also started a very tough exam to find the best Americans for these jobs. It also created a system where promotions were based on how well people performed.

The Rogers Act set up two important boards. The Board of the Foreign Service advises the Secretary of State on managing the Foreign Service. The Board of Examiners manages the testing process.

Over time, other government agencies also sent their representatives abroad. In 1927, the Department of Commerce's "trade commissioners" gained diplomatic status. In 1930, the Department of Agriculture's representatives also got this status. Later, these roles were moved between departments.

The Foreign Service Act of 1946

In 1946, Congress passed a new law for the Foreign Service. It created six types of employees:

- Chiefs of mission (like ambassadors)

- Foreign Service Officers (FSOs)

- Foreign Service Reservists

- Foreign Service Staff

- "Alien personnel" (now called Locally Employed Staff)

- Consular agents

FSOs were expected to work mostly overseas. They were like commissioned officers, ready to serve anywhere in the world. This law also brought in the "up-or-out" system. This means if an officer doesn't get promoted to a higher rank within a certain time, they must retire. This system helps keep the service strong and active.

The 1946 Act also created the position of Director General of the Foreign Service. It set up mandatory retirement ages for officers.

The Foreign Service Act of 1980

The Foreign Service Act of 1980 is the most recent major law for the Foreign Service. It changed how personnel were managed. It created the Senior Foreign Service, which has ranks similar to generals in the military.

This law also added "danger pay" for diplomats serving in risky places. It reauthorized the Board of the Foreign Service. This board advises the Secretary of State on how to manage the Foreign Service. It also ensures that different agencies using the Foreign Service system work well together.

Who Are Foreign Service Members?

The Foreign Service Act defines different types of members:

- Chiefs of Mission: These are leaders like ambassadors. The President appoints them, and the Senate approves.

- Ambassadors at Large: These are also appointed by the President and approved by the Senate.

- Senior Foreign Service (SFS) members: These are top leaders and experts. They are appointed by the President and approved by the Senate. They are similar in rank to generals in the military.

- Foreign Service Officers (FSOs): Often called "generalists," they are the main diplomats. They carry out the Foreign Service's work. The President appoints them, and the Senate approves.

- Foreign Service Specialists: These members provide special skills. This includes IT specialists, nurses, and security agents. The Secretary of State appoints them.

- Foreign Service Nationals (FSNs): These are local staff who provide support at overseas offices. They are often citizens of the host country.

- Consular agents: They offer consular services in places without a full Foreign Service office.

Also, Diplomats in Residence are senior FSOs who help recruit new members. They work in different regions and often hold positions at local universities.

Agencies in the Foreign Service

Most Foreign Service employees work for the Department of State. However, the 1980 Act allows other U.S. government agencies to use this personnel system for overseas jobs. These include:

- The Department of Commerce (Foreign Commercial Service)

- The Department of Agriculture (Foreign Agricultural Service)

- The United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

Senior FSOs from these agencies can even become ambassadors.

How Big is the Foreign Service?

The Foreign Service has about 15,600 members, not counting Foreign Service Nationals. This includes:

- Nearly 8,000 Foreign Service Officers (generalist diplomats)

- Almost 5,800 Foreign Service Specialists

- About 1,700 at USAID

- Over 200 in the Foreign Commercial Service

- Around 150 in the Foreign Agricultural Service

- About 40 from APHIS

- A small number from the U.S. Agency for Global Media

How to Join the Foreign Service

The process for joining the Foreign Service is different for each type of position. For most Department of State Foreign Service Officers and Specialists, the steps are:

- Initial application

- Qualifications Evaluation Panel (QEP) review

- Oral Assessment

- Background checks and final review

- Placement on the hiring list (the "Register")

All evaluation steps look for certain personality traits and skills. For Generalists, there are 13 key traits. For Specialists, there are 12. Knowing these traits can really help a candidate.

Starting Your Application

For Generalists, the first step is the Foreign Service Officer Test (FSOT). For Specialists, it's an application on USAJobs.

The FSOT Exam

Generalist candidates take the FSOT. This written test has sections on job knowledge, hypothetical situations, English grammar, and an essay. If you pass the FSOT, you then write short essays called Personal Narrative Questions (PNQs). These are reviewed by the Qualifications Evaluation Panel (QEP). Only about 25-30% of candidates pass both the FSOT and the PNQ/QEP stage.

Less than 10% of those who pass the FSOT are invited to an oral assessment. This is given in person in Washington, D.C. or other major U.S. cities. About 10% of the original applicants will pass this final assessment.

USAJobs Applications

Specialists fill out applications specific to their skills. Since specialties vary, so do the applications. Candidates describe their experience and provide references.

Qualifications Evaluation Panel (QEP)

For Generalists, you first submit your Personal Narrative Questions. These are usually six essays asking for examples of how you've handled challenges, based on the 13 personality traits. Soon after, you take the FSOT. If your FSOT score is high enough, your essays are reviewed by a QEP. This panel is made up of three current Foreign Service Officers. You must pass both the FSOT and the QEP review to be invited to the Oral Assessment.

Specialists also go through a QEP. Their essays are part of their initial USAJobs application. Experts review Specialist candidates' skills and recommend them for an oral assessment.

Oral Assessments

The oral assessment is different for Generalists and Specialists. Specialists have a structured interview, a written test, and often an online exam. Generalists have a written test, a structured interview, and a group exercise.

All parts of the oral assessment are scored on a seven-point scale. To continue, candidates need a score of 5.25 or higher. Passing this assessment gives a candidate a conditional job offer.

Background Checks and Final Review

Next, candidates must get a worldwide medical clearance and a top-secret security clearance. They also need a "suitability" clearance. This means they are fit for the job. Once all information is gathered, a Final Suitability Review decides if the candidate is right for the Foreign Service. If so, their name goes on the "Register."

If a candidate fails to get any of these clearances, their application ends. It can be hard to get a top-secret clearance if you have a lot of foreign travel, dual citizenship, or financial issues.

The Register: Waiting for a Call

Once a candidate passes all checks, they are placed on the "Register." This is a list of eligible hires, ranked by their oral assessment score. Factors like foreign language skills or Veteran's Preference can boost a score. Candidates stay on the Register for 18 months. If they aren't hired within that time, their application ends. There are separate registers for each career field.

Successful candidates from the Register receive job offers to join a Foreign Service Class. Generalists and Specialists attend different training courses. Generalists attend a 6-week course called A-100 at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) in Arlington, Virginia. Specialist training at FSI is 3 weeks long. After this, employees get more training before their first assignment.

All Foreign Service personnel must be "worldwide available." This means they can be sent anywhere in the world based on the needs of the service. They also agree to publicly support U.S. government policies.

Life as a Foreign Service Member

Foreign Service members are expected to spend much of their careers abroad. They work at embassies and consulates around the world. There are rules about how long they can serve in the U.S. before going overseas again. Working abroad has both challenges and benefits, especially for families.

Family members usually go with Foreign Service employees overseas. However, in dangerous areas, assignments might be "unaccompanied." Children of Foreign Service members, sometimes called Foreign Service brats, grow up in a unique way. They experience different cultures and move often.

Many children of Foreign Service members become very adaptable and good at making friends. They enjoy international travel. However, some children find it hard to adjust to this lifestyle. For both employees and their families, seeing the world and experiencing foreign cultures are big benefits. The strong friendships within the Foreign Service community are also a plus.

Some downsides include exposure to tropical diseases and poor healthcare in some countries. There's also the risk of violence, civil unrest, and war. Attacks on U.S. embassies, like those in Nairobi or Benghazi, show these dangers. Personnel in countries with weak infrastructure also face risks from fires, accidents, and natural disasters.

It can be hard to have a personal life outside the Foreign Service. While rare, there have been cases of people misusing their position for money, such as selling visas.

Foreign Service members must agree to work anywhere in the world. They usually have a say in where they go, but assignments depend on the service's needs. Many employees volunteer for difficult posts, even in dangerous places like Iraq and Afghanistan.

The State Department has a Family Liaison Office. This office helps diplomats and their families deal with the unique challenges of this life. This includes long family separations when an employee is sent to a danger zone.

Challenges: "Clientitis"

Clientitis is a term used to describe when staff in a foreign country start to see the host country's officials as their "clients." This means they might start defending the actions of that foreign government. It's like "going native."

For example, an American Foreign Service Officer might start automatically defending the host country's government. This means they've started to see the host country's officials as the people they serve, rather than focusing on U.S. interests. Former Ambassador John Bolton has often used this term to describe a mindset he saw in the State Department.

The State Department trains new ambassadors about the danger of clientitis. To prevent it, FSOs are rotated to new countries every 2–3 years. This helps them avoid becoming too focused on one place.

Foreign Service Career System

The Foreign Service has a special career system. Both generalist and specialist positions are promoted based on their performance each year. Each foreign affairs agency has rules about how long someone can stay in a certain rank or service. For example, if a member isn't promoted to the Senior Foreign Service within 27 years, they might have to retire.

Also, review boards can recommend that members leave the service if they don't perform as well as their peers. This "up or out" system is similar to the military. It encourages members to perform well and to take on difficult and risky assignments.