Ukawsaw Gronniosaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1705 |

| Died | 28 September 1775 |

| Burial place | St Oswald's, Chester |

| Other names | James Albert |

| Known for | His autobiography |

| Children | 5 |

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (born around 1705 – died September 28, 1775), also known as James Albert, was an African man who was forced into slavery. He is important because he was the first African person in Britain to have his story published.

Gronniosaw is famous for his book, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself. This book came out in 1772. It was the first slave narrative (a story written by someone who was enslaved) ever published in England. His book shared details about his early life in what is now Nigeria, how he was enslaved, and how he eventually became free.

Contents

His Early Life and Freedom

Gronniosaw was born in Bornu Empire (now part of north-eastern Nigeria) around 1705. He said he was the grandson of the king of Zaara and was much loved.

Enslaved and Brought to America

When he was about 15, he was captured by an ivory merchant from the Gold Coast. This merchant sold him to a Dutch ship captain. Gronniosaw was then bought by an American in Barbados.

He was taken to New York and sold again for £50. His new owner was "Mr. Freelandhouse," a kind minister. This minister was likely Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen, a Dutch Reformed Church minister in New Jersey.

Learning and Becoming Free

In New York, Gronniosaw learned to read and became a Christian. He wrote in his book that he wanted to go back to his family in Africa. However, Frelinghuysen told him to focus on his Christian faith instead.

When the minister died, he made sure Gronniosaw was freed in his will. Gronniosaw then worked for the minister's widow and their children. Sadly, they all passed away within four years.

Journey to England

Gronniosaw decided to travel to England. He hoped to find other religious people there, like the Frelinghuysens. To earn money for his trip, he first went to the Caribbean.

- He worked as a cook on a privateer ship (a private ship allowed to attack enemy ships).

- Later, he joined the 28th Regiment of Foot as a soldier.

- He served in places like Martinique and Cuba.

- After leaving the army, he finally sailed to England.

Life in England

Gronniosaw first settled in Portsmouth. But his landlady cheated him out of most of his money. So, he had to move to London to find work.

Marriage and Hard Times

In London, he married a young English widow named Betty, who worked as a weaver. Betty already had one child, and they had at least two more together.

Betty lost her job because of money problems and worker protests. The family then moved to Colchester. They were saved from starving by Osgood Hanbury, a Quaker lawyer. He hired Gronniosaw for building work.

The family later moved to Norwich. They faced hard times again because building jobs were not available all year. Another kind Quaker, Henry Gurney, helped them by paying their overdue rent.

Family and Faith

Sadly, one of their daughters died. The local church leaders refused to bury her because she had not been baptized. Finally, one minister allowed her to be buried in the churchyard. However, he would not read the burial service.

After selling almost everything they owned, the family moved to Kidderminster. There, Betty supported them by working as a weaver again.

On Christmas Day in 1771, Gronniosaw had his remaining children baptized. These were Mary Albert (age six), Edward Albert (age four), and newborn Samuel Albert. The baptism happened at the Old Independent Meeting House in Kidderminster. The minister was Benjamin Fawcett, who was connected to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

Around this time, Gronniosaw received a letter and a gift of money from Countess Hastings. He wrote back on January 3, 1772, thanking her for her help. He explained that her gift arrived when they really needed it.

On June 25, 1774, Gronniosaw's fifth child, James Albert junior, was also baptized by Fawcett.

Writing His Story

Soon after arriving in Kidderminster, Gronniosaw began writing his life story. He had help from a writer (called an amanuensis) from Leominster. This person might have been "Mrs Marlowe," whom he mentioned in his letter to Countess Hastings.

Scholars have studied Gronniosaw's Narrative as a very important work. It was written by an African person in English. It is the first known slave narrative published in England. The book became very popular, with many copies printed at the time.

Gronniosaw's Narrative ends with him living in Kidderminster, appearing to be "turn'd sixty" (over 60 years old). For a long time, people did not know what happened to him after that.

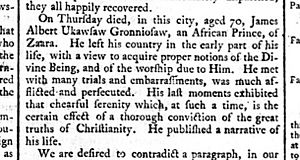

However, an obituary (a death notice) for Gronniosaw was found in the Chester Chronicle newspaper. The article, from October 2, 1775, said: On Thursday [September 28] died, in this city, aged 70, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, of Zaara. He left his country in the early part of his life, with a view to acquire proper notions of the Divine Being, and of the worship due to Him. He met with many trials and embarrassments, was much afflicted and persecuted. His last moments exhibited that chearful serenity which, at such a time, is the certain effect of a thorough conviction of the great truths of Christianity. He published a narrative of his life.

The burial records for St Oswald, Chester, show an entry from September 28, 1775, for "James Albert (a Blackm[an])", who was 70 years old. Gronniosaw's exact grave location is not known.

About His Autobiography

Gronniosaw's autobiography was created in Kidderminster in 1772. Its full title is A Narrative of the Most remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, As related by himself. The title page also says it was "committed to paper by the elegant pen of a young LADY of the town of LEOMINSTER."

This book is the first slave narrative written by an African person in the English language. It is a type of literature where enslaved people share their stories after gaining freedom. Published in Bath, Somerset, in December 1772, it gives a clear account of Gronniosaw's life. It covers his journey from leaving home to being enslaved in Africa by a local king. It also describes his time as an enslaved person and his struggles with poverty as a free man in Colchester and Kidderminster. He liked Kidderminster because it was once home to Richard Baxter, a 17th-century minister he admired.

The Preface and Its Meaning

The introduction to the book was written by Reverend Walter Shirley. He was a cousin of Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. She supported a branch of Methodism called Calvinistic Methodism. Shirley saw Gronniosaw's experience of being enslaved and brought from Bornu to New York as an example of God's plan.

Scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. has pointed out that Gronniosaw's story was different from later slave narratives. Later stories usually criticized slavery as a bad system. In his book, Gronniosaw mentioned his "white-skinned sister." He also said he was willing to leave Africa because his family believed in many gods, not just one all-powerful God. He learned more about this one God through Christianity. He also suggested he became happier as he fit into white English society, especially through language. He even described another black servant as a "devil." Gates concluded that Gronniosaw's story does not have an anti-slavery message, which became common in later slave narratives.

Until his 1775 obituary and a letter he wrote were found, the Narrative was the only main source of information about his life.

See also

Additional sources

- Echero, Michael. "Theologizing 'Underneath the Tree': an African topos in Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, William Blake, and William Cole". Research in African Literatures. 23.4 (Winter 1992). 51–58.

- Harris, Jennifer. "Seeing the Light: Re-Reading James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw". English Language Notes 42.4, 2005: 43–57.