Vivien Thomas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vivien Thomas

|

|

|---|---|

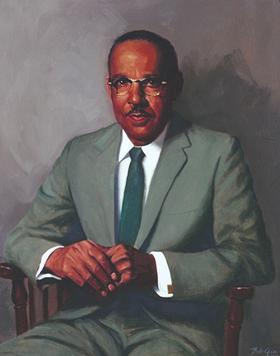

Thomas' 1969 portrait by Bob Gee presented in 1971 to the medical institution. Thomas was recognized for his contributions to the astounding developmental techniques that surgeons still use today.

|

|

| Born |

Vivien Theodore Thomas

August 29, 1910 |

| Died | November 26, 1985 (aged 75) |

| Education | Pearl High School |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Instructor of Surgery |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins Hospital, Vanderbilt University Hospital |

| Research | Blue baby syndrome |

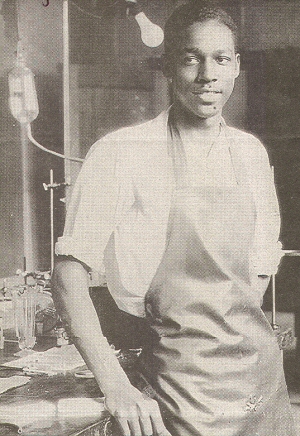

Vivien Theodore Thomas (born August 29, 1910 – died November 26, 1985) was an American laboratory supervisor. He helped create a surgery to treat a heart problem called blue baby syndrome. This condition is now known as cyanotic heart disease. He worked with surgeon Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University and later at Johns Hopkins University.

Vivien Thomas was special because he didn't have a medical degree. He only finished high school. But he became the supervisor of surgical labs at Johns Hopkins for 35 years. In 1976, Johns Hopkins gave him an honorary doctorate degree. They also made him an instructor of surgery. Thomas overcame poverty and racism. He became a pioneer in cardiac surgery and taught many top surgeons.

His life story was shown in a PBS documentary called Partners of the Heart in 2003. In 2004, the HBO movie Something the Lord Made featured his story.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Vivien Thomas was born in Lake Providence, Louisiana. His family moved to Nashville, Tennessee in 1912. They moved because of yearly floods from the Mississippi River. This move helped them avoid having to leave their home often.

Thomas went to Pearl High School in Nashville. He graduated in 1929. His father was a carpenter and taught his sons his skills. Vivien worked with his father and brothers after school. This experience helped him get a carpentry job at Fisk University.

Thomas wanted to go to college and become a doctor. But the Great Depression made it hard to achieve his dream. He planned to save money and go to college later. In 1930, he found a job through a friend.

Career Beginnings

In February 1930, Thomas got a job as a surgical research assistant. He worked with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University. On his first day, Thomas helped Blalock with a surgery experiment on a dog. Soon, Thomas was setting up surgeries on his own.

Even though he did advanced work, Thomas was paid like a janitor. This was much less than white men doing the same job. Nine months after he started, Nashville's banks failed. Thomas lost all his savings. He gave up his plans for college and medical school. He was just glad to have a job during the Great Depression.

Working with Dr. Blalock

Research at Vanderbilt

Thomas and Blalock did important research on shock. This work helped save many soldiers' lives in World War II. They showed that shock was caused by fluid loss, not toxins. They proved that replacing fluids could treat it. This made Blalock well-known in the medical world.

They also started working on heart surgery. This was a new and risky area of medicine. Their work at Vanderbilt set the stage for the life-saving surgery they would do later. Vivien Thomas worked with Blalock at Vanderbilt for 11 years.

Moving to Johns Hopkins

By 1940, Blalock's work with Thomas made him a top surgeon. In 1941, Blalock became Chief of Surgery at Johns Hopkins University. He asked Thomas to come with him. Thomas and his family moved to Baltimore in June 1941.

They faced a housing shortage and more racism than in Nashville. Johns Hopkins was segregated. Most Black employees were janitors. When Thomas wore his white lab coat, people stared. He started changing into his regular clothes when he walked around the hospital.

Solving Blue Baby Syndrome

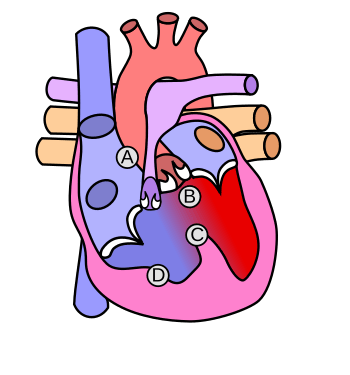

In 1943, a heart doctor named Helen Taussig asked Blalock for help. She needed a surgery for a serious heart problem. This problem was called tetralogy of Fallot, or blue baby syndrome. Babies with this condition had blue skin because their blood didn't get enough oxygen.

Blalock and Thomas realized they could use a procedure they had practiced. It involved connecting two arteries to increase blood flow to the lungs. Thomas's job was to create a "blue baby" condition in dogs. Then he would fix it with the new procedure.

One dog, named Anna, was the first to survive the operation long-term. Her portrait hangs at Johns Hopkins. Thomas worked for almost two years on 200 dogs. He showed that the surgery was safe. Blalock was very impressed with Thomas's work. He said, "This looks like something the Lord made."

The First Human Surgery

On November 29, 1944, the surgery was tried for the first time. The patient was an 18-month-old baby named Eileen Saxon. Her lips and fingers were blue. She could barely walk without getting out of breath.

There were no special tools for heart surgery then. Thomas adapted tools from the animal lab. During the surgery, Thomas stood on a stool next to Blalock. He coached Blalock step-by-step through the procedure. Thomas had done the operation hundreds of times on dogs. Blalock had only done it once, as Thomas's assistant.

The first surgery helped Eileen live longer. Later, they operated on an 11-year-old girl and a 6-year-old boy. Both surgeries were very successful. The boy's skin color returned to normal right after the operation. A report about the surgery was published in a medical journal. It gave credit to Blalock and Taussig. Thomas was not mentioned.

News of this amazing surgery spread worldwide. It made Johns Hopkins and Blalock very famous. But Thomas's important role was not recognized by Blalock or the hospital at first.

Thomas's Surgical Skills

Vivien Thomas developed many surgical techniques. One was for improving blood flow in patients with transposed great vessels of the heart. He performed this complex surgery so perfectly. Blalock once said, "Vivien, this looks like something the Lord made."

Many young surgeons learned from Thomas in the 1940s. They saw him as a legend. Famous surgeon Denton Cooley said, "Even if you'd never seen surgery before, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple." Surgeons like Cooley and others said Thomas taught them the skills that made them leaders in medicine.

Despite this respect, Thomas was not paid well for a long time. He sometimes worked as a bartender to earn more money. By 1946, after Blalock's help, he became the highest-paid assistant at Johns Hopkins. He was also the highest-paid African-American employee there.

Thomas always wanted to go to college and become a doctor. But he realized he would be too old by the time he finished. So, he gave up that dream.

Relationship with Blalock

Vivien Thomas was nervous when he first met Dr. Alfred Blalock. But he found Blalock pleasant and informal. Thomas quickly learned that Blalock worked fast and expected the same from his team. Thomas watched Blalock closely so he could do experiments on his own.

Sometimes, Blalock would get angry. This bothered Thomas and almost caused problems in their work. Thomas also struggled with his low salary. He almost left to go back to carpentry. But Blalock saw how valuable Thomas was and kept him from leaving.

Blalock's view on race was complicated. He defended Thomas to his bosses and insisted Thomas be in the operating room. But he also limited Thomas's pay and public recognition. Thomas was not in official articles or team photos about the blue baby procedure. This caused tension between them.

After Blalock died in 1964, Thomas stayed at Hopkins for 15 more years. He led the Surgical Research Laboratories. He mentored many Black lab assistants. He also helped Levi Watkins, Jr., Hopkins' first Black cardiac resident.

Thomas's nephew, Koco Eaton, later graduated from Johns Hopkins Medical School. He was trained by many doctors his uncle had taught.

Recognition and Legacy

In 1968, the surgeons Thomas had trained commissioned a portrait of him. It was hung next to Blalock's portrait in a main building.

In 1976, Johns Hopkins University gave Thomas an honorary doctorate. This allowed staff and students to call him "Doctor." After 37 years, he was also made an Instructor of Surgery. Because he didn't have a medical degree, he was never allowed to operate on human patients.

In 2005, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine named one of its new student colleges after Vivien Thomas. This honored his major impact on medicine.

Personal Life and Death

Vivien Thomas married Clara Beatrice Flanders in 1933. They had two daughters, Olga Fay and Theodasia Patricia. In 1941, the family moved to Baltimore for Thomas's work with Blalock.

In 1971, Thomas was finally honored for his work behind the scenes. He gave a humble speech, saying he was happy to help solve health problems. He was overjoyed to finally get credit for his important role.

Dr. Thomas retired in 1979. He then started writing his autobiography. He died of pancreatic cancer on November 26, 1985. His book was published just days later.

Lasting Impact

Vivien Thomas's story became widely known through a 1989 article. This article inspired the PBS documentary Partners of the Heart and the HBO film Something the Lord Made.

His legacy continues with the Vivien Thomas Young Investigator Awards. These awards are given for excellence in cardiovascular surgery research. The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation also created the Vivien Thomas Scholarship for Medical Science and Research. In 2004, the Baltimore City Public School System opened the Vivien T. Thomas Medical Arts Academy. A copy of his portrait hangs in the school's halls.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center also created the Vivien A. Thomas Award. This award recognizes excellence in clinical research.

See also

In Spanish: Vivien Thomas para niños

In Spanish: Vivien Thomas para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |