Volcán de Fuego facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Volcán de Fuego |

|

|---|---|

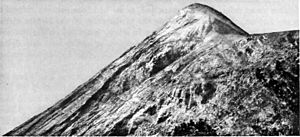

Volcán de Fuego in 2012

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,768 m (12,362 ft) |

| Prominence | 469 m (1,539 ft) |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Volcano of Fire |

| Language of name | Spanish |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Sierra Madre |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 200 kyr |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Central America Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 2002 to 2024 (ongoing) |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Fuego volcano |

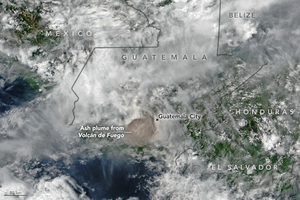

Volcán de Fuego (which means "Volcano of Fire" in Spanish) is a very active stratovolcano in Guatemala. It's often just called Fuego. In the Kaqchikel language, it's known as Chi Q'aq' which means "where the fire is." This volcano sits on the borders of three different areas: Chimaltenango, Escuintla, and Sacatepéquez.

Fuego is part of the Sierra Madre mountain range. It's about 16 kilometers (10 miles) west of Antigua, a famous city and tourist spot in Guatemala. This volcano erupts often! Some recent eruptions happened in June and November 2018, September 2021, December 2022, and May 2023.

Volcán de Fuego is known for being almost always active, even if it's just a little bit. Small explosions of gas and ash happen every 15 to 20 minutes. Bigger eruptions are less common. The volcano is connected to Acatenango volcano to its north. Together, they are called La Horqueta. Between them is La Meseta, which is what's left of an older volcano that collapsed about 8,500 years ago. Fuego started growing after La Meseta collapsed.

Contents

Exploring Volcán de Fuego

In 1881, a French writer named Eugenio Dussaussay climbed the volcano. Back then, very few people had explored it. He had to get special permission from the governor to climb. The governor even gave him a letter for the mayor of Alotenango, asking for guides to help him and his friend, Tadeo Trabanino. They wanted to reach the central peak, but couldn't find a guide. So, they climbed to the active cone, which had erupted recently in 1880.

A British archaeologist named Alfred Percival Maudslay also climbed the volcano on January 7, 1892. He wrote about his adventure:

[...] we started from Alotenango around 7 in the morning with seven helpers. They carried our food, clothes, and my camp-bed. We rode for an hour towards the mountains, then got off our mules. The first two hours of climbing weren't too steep, but walking over loose dirt and dry leaves in the thick forest was tiring. [...] we continued climbing a steep path through the forest. At about 9,500 feet, we finally saw the peak of Fuego across a deep valley. The slope we saw had no plants, just ash and burnt rocks. We kept going through thick plants, often on loose ground. As we climbed higher, the plants changed, and we saw pine trees. Around 11,200 feet, we found a flat spot where Native Americans had cleared the earth, and we decided to spend the night there. [...] We watched the sunset over the distant peaks and against the perfect cone of Agua. [...] The cold after sunset quickly got our attention. [...] We left our shelter around 4:30 in the morning and felt better after hot coffee. We then watched a beautiful sunrise for an hour. On the other side of the valley was the Volcano of Agua, sloping down to the plain of Antigua on one side, and all the way to the sea, more than forty miles away, on the other. Many peaks appeared against the red light far away, and on the right, the low coastline and the sea were very clear. As soon as the sun was up, we started for the top. I tried to take a picture of the cone, which was to our left as we went up, but clouds came just as I was ready, so I gave up. A little over 12,000 feet, we left the small pine trees and reached the northern end of a ridge made of cinders, called the Meseta, which was at the top of the slope we had been climbing.

Major Eruptions of Fuego

| Date | What Happened |

|---|---|

| 1581 | These eruptions were reported by a historian named Domingo Juarros. They caused damage nearby. It's possible that earthquakes also played a part. |

| 1586 | |

| 1623 | |

| 1705 | |

| 1710 | |

| August 27–30, 1717 | A powerful eruption happened just before the San Miguel earthquake. |

| 1732 | Also reported by Domingo Juarros. These eruptions caused damage in the surrounding areas. Earthquakes might have been involved too. |

| 1737 | |

| Around 1800 | This eruption lasted several days. It didn't cause a disaster, but it made a nearby stream so hot that animals wouldn't cross it! |

| 1880 | This eruption was mentioned by Eugenio Dussaussay. |

| 1932 | A strong eruption that covered Antigua Guatemala in ash. |

| October 15–21, 1974 | A powerful eruption that caused a lot of damage to farms. Hot, fast-moving flows of gas and rock (called pyroclastic flows) destroyed all plants near the volcano's top. |

| July 1–6, 2004 | A small eruption that followed some explosions inside the volcano. |

| August 9, 2007 | A small eruption of lava, rocks, and ash. About seven families living near the volcano had to leave their homes for safety. |

| September 13, 2012 | The volcano started shooting out lava and ash. Officials had to help thousands of people move to safety from five communities. About 33,000 people left nearly 17 villages near the volcano. Lava and pyroclastic flows traveled about 600 meters (2,000 feet) down the volcano's side. |

| February 8, 2015 | Another eruption caused 100 nearby residents to be moved to safety. La Aurora International Airport had to close because of all the ash falling. |

| May 5, 2017 | An eruption led to 300 residents from Panimache and Sangre de Cristo being moved to safety. Strong explosions created shock waves and thick ash clouds that rose 1.3 kilometers (0.8 miles) above the crater. The ash drifted more than 50 kilometers (31 miles) away, and ash fell in many areas. |

| June 3, 2018 | This eruption was very powerful. Hot, fast-moving flows of gas and rock unexpectedly reached villages like El Rodeo, Las Lajas, and San Miguel Los Lotes in Escuintla. Many people were affected, and residents had to be moved to safety. La Aurora International Airport also closed due to ash. |

| 20 November 2018 | Another eruption. About 4,000 people from communities near the volcano were moved to safety as a precaution. |

| 23 September 2021 | An eruption that produced an ash column and hot, fast-moving flows of gas and rock down several ravines. No one had to be moved to safety during this eruption. |

| 7 March 2022 | An eruption that created ash plumes, fire fountains, and hot, fast-moving flows (up to 7 km or 4.3 miles) in several ravines. Around 500 people from nearby communities were moved to safety. |

| 4 May 2023 | An eruption that produced ash and hot, fast-moving flows. Several communities were moved to safety by CONRED (Guatemala's disaster response agency). |

The 1717 Earthquakes and Santiago de los Caballeros

Before the city of Santiago de los Caballeros finally moved in 1776, it experienced very strong earthquakes in 1717, known as the San Miguel earthquakes. People in the city believed that the nearby Volcán de Fuego caused these earthquakes. A famous architect, Diego de Porres, even thought all earthquakes were from volcano explosions.

On August 27, 1717, Volcán de Fuego had a powerful eruption that lasted until August 30. People in the city prayed for help. On August 29, a special procession with the Virgen del Rosario statue took place, something that hadn't happened in a century. Many other holy processions followed until September 29. In the early afternoon, the earthquakes were small, but around 7:00 PM, a strong one hit, forcing people out of their homes. Tremors and rumblings continued until four in the morning. People went into the streets, confessing their sins and preparing for the worst.

The San Miguel earthquake greatly damaged the city. Parts of the Royal Palace were destroyed. Many people left the city, and there were food shortages and not enough workers. The city's buildings were badly damaged, and sadly, many people were hurt or lost their lives. These earthquakes made the authorities think about moving the city to a safer place. But the city residents strongly disagreed and even protested at the Royal Palace. In the end, the city didn't move right away. The damage to the palace was fixed by Diego de Porres by 1720.

In 1773, the Santa Marta earthquakes destroyed much of the town again. This led to the city moving for the third time. In 1776, the Spanish Crown ordered the capital to move to a safer spot. This new place is where Guatemala City, the current capital of Guatemala, stands today. The new city was named Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción (New Guatemala of the Assumption). The badly damaged city of Santiago de los Caballeros was ordered to be abandoned. However, not everyone left, and it became known as la Antigua Guatemala (the Old Guatemala).

The Big Eruption of June 3, 2018

Volcán de Fuego is one of the world's most active volcanoes. It's also very close to many towns and cities. Sometimes, its eruptions happen very suddenly, making it hard to move people to safety in time. Since 2002, Volcán de Fuego has been continuously active. It has monthly eruptions that usually send ash falling on communities within 20 kilometers (12 miles) of the volcano. Lava flows typically travel about 1-2 kilometers (0.6-1.2 miles) from the top, and sometimes there are hot, fast-moving flows of gas and rock.

On June 3, 2018, the volcano had its most powerful eruption since 1974. Large, hot, fast-moving flows of gas and rock (called pyroclastic density currents) overflowed their usual paths. They unexpectedly hit the villages of El Rodeo, Las Lajas, San Miguel Los Lotes, and La Reunión in Escuintla. These flows buried the towns and affected many surprised residents.

Ash fell as far away as the capital, Guatemala City. This forced La Aurora International Airport to close. The military helped clear ash off the runway. Rescue efforts were very difficult because the roads into the affected areas were badly damaged by the pyroclastic flows. On June 5, the Associated Press reported that many people were affected, and hundreds were still missing after the eruption.

See also

In Spanish: Volcán de Fuego para niños

In Spanish: Volcán de Fuego para niños

- List of volcanoes in Guatemala

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |