Wallisian language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wallisian |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fakaʻuvea | ||||

| Native to | Wallis and Futuna | |||

| Native speakers | 10,400 (2000)e18 | |||

| Language family |

Austronesian

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

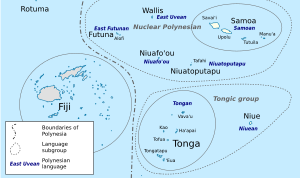

Wallisian, also called ʻUvean (Wallisian: Fakaʻuvea), is a Polynesian language. People speak it on Wallis Island, which is also known as ʻUvea. It's sometimes called East Uvean to tell it apart from the West Uvean language. That language is spoken on a different island called Ouvéa, near New Caledonia. People from Wallis Island settled Ouvéa in the 1700s.

Wallisian is native to Wallis Island. Many people also speak it in New Caledonia. This is because many Wallisians moved there starting in the 1950s. They mostly live in cities like Nouméa and Dumbéa. In 2015, about 7,660 people spoke Wallisian. However, some experts believe the real number is much higher, possibly around 20,000 speakers.

The language most similar to Wallisian is Niuafo'ou. Wallisian is also closely related to Tongan. It has borrowed many words from Tongan. This happened because Tongan people invaded Wallis Island in the 1400s and 1500s. Wallis Island was first settled about 3,000 years ago.

Contents

Alphabet and Sounds

Wallisian has 10 vowel sounds. There are 5 basic vowels: /a, e, i, o, u/. Each of these also has a longer version: ā, ē, ī, ō, ū.

| Lip sounds | Tongue-to-ridge sounds | Back-of-mouth sounds | Throat sounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ ⟨g⟩ | |

| Plosive | p | t | k | ʔ ⟨ʻ⟩ |

| Fricative | f v | s | h | |

| Approximant | l |

Writing Wallisian

The symbol ʻ is used in Wallisian writing. It stands for a sound called a glottal stop. This is like the sound in the middle of "uh-oh." In Wallisian, this symbol is called fakamoga. It can look like a straight, curly, or upside-down apostrophe.

Another mark used is the macron (ā). It shows that a vowel sound is long. However, people don't always write the macron. For example, Mālō te maʻuli (hello) can also be written as Malo te mauli.

For a long time, Wallisian was only a spoken language. The first Wallisian vocabulary list was made by a French missionary, Pierre Bataillon, in 1840. It was updated later but not published until 1932. A German linguist, Karl Rensch, used this work to create a Wallisian-French dictionary in 1948. He decided not to use the macron in his dictionary.

Vocabulary and Word Use

| Sound | Old Polynesian | Samoan | Tongan | Niuafo'ou | East Futunan | Wallisian | West Uvean | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ŋ/ | *taŋata | tagata | tangata | tangata | tagata | tagata | tagata | man, person |

| /s/ | *sina | sina | hina | sina | hina | sina | grey (of hair) | |

| /ti/ | *tiale | tiale | siale Tonga | siale | tiale | siale | tiale, tiare | flower (Gardenia Taitensis) |

| /k/ | *waka | vaʻa | vaka | vaka | vaka | vaka | vaka | canoe |

| /f/ | *fafine | fafine | fefine | fafine | fafine | fafine | fafine | woman |

| /ʔ/ | *matuqa | matua | motuʻa | matua | matuʻa | parent | ||

| /r/ | *rua | lua | ua | ua, lua | lua | lua | lua | two |

| /l/ | *tolu | tolu | tolu | tolu | tolu | tolu | tolu | three |

Different Ways of Speaking

In Wallisian, people use different ways of speaking depending on who they are talking to. These are called "registers." There are three main registers:

- Honorific language: This is a very respectful way of speaking. Common people use it when talking to or about royal family members or God. Royal family members also use it among themselves.

- Commoner language: This is the everyday, "ordinary" Wallisian that most people use in regular conversations.

- Vulgar or derogatory language: This is language that is rude or offensive. It is used in specific, disrespectful situations.

For example, the word for "to remain" changes depending on the register. In honorific language, it's ‘afio. In commoner language, it's nofo. In vulgar language, it's tagutu. Each word is used in its proper situation.

History and Language Family

Wallisian is a Polynesian language. It developed from an older language called Proto-Polynesian. Experts have discussed how to classify Wallisian. Because it is very similar to Tongan, some thought it belonged to the "Tongic" group of languages. However, later linguists decided it is part of the "Nuclear Polynesian" group.

The language most like Wallisian is Niuafo'ou. This language is spoken on the island of Niuafo'ou in Northern Tonga. People who speak Wallisian and Niuafo'ou can understand each other very well. This is because the islands had a lot of contact until the mid-1900s.

Words from Other Languages

Wallisian has borrowed many words from other languages over time.

From Tongan

Wallisian is closely related to Tongan. This is because Tonga invaded Wallis Island a long time ago. For example, the past tense word ne'e in Wallisian comes from Tongan. Wallisian is very similar to Tongan, while the Futunan language is more like Samoan.

From English

In the 1800s, Wallisians used a simple form of English, called pidgin, to talk with traders. Many whaling ships from New England often stopped at Wallis and Futuna. About 70 pidgin words are still used on Wallis Island today. Trade with places like Fiji stopped in 1937 because of a coconut beetle problem on Wallis Island.

English loanwords included names for European foods like laisi (rice) and suka (sugar). They also borrowed words for objects like pepa (paper) and some animals like hosi (horse).

The influence of English grew even more after the American army built a military base on the island in 1942. More English words became part of Wallisian. Examples include puna (spoon), motoka (car, from "motor car"), famili (family), peni (pen), and tini (tin).

From Latin

When missionaries arrived, they brought many Latin words, especially for religious terms. For example, Jesus Christ became Sesu Kilisito. Words like komunio (communion) and kofesio (confession) also came from Latin. Some everyday words were borrowed too, such as hola (time, hour) and hisitolia (history).

Not all religious words were borrowed directly. Missionaries also used existing Wallisian words and gave them new Christian meanings. For instance, Tohi tapu (sacred book) means the Bible. Aho tapu (holy day) means Sunday, and Po Tapu (sacred night) is Christmas. The idea of the Trinity was translated as Tahitolu tapu, meaning "one-three holy." Missionaries also introduced the names for the days of the week, using a Latin style similar to Portuguese.

When Wallisian borrows words, it changes them to fit its own sound rules. For example, it might add a vowel in the middle of a word or change the end of a word.

From French

French has had a big impact on Wallisian. French missionaries arrived in the late 1800s. In 1961, Wallis and Futuna became a French overseas territory, and French is now the official language.

At first, French did not change Wallisian much. But now, it is having a deep effect. Many new words have been created by changing French words to fit Wallisian sounds. This is common in words about politics, like Falanise (France), Telituale (Territory), politike (politics), and Lepupilika (Republic). Many technical words like telefoni (telephone) and televisio (television) are also borrowed. Words for foods brought by Europeans, such as tomato, tapaka (tobacco), alikole (alcohol), and kafe (coffee), also come from French.

In the 1980s, more and more French words were entering Wallisian. By the 2000s, young people started mixing both languages when they spoke.

French influence is also seen in media and schools. French became the main language in schools in 1961. This helped France keep its control over the island. In the late 1960s, if a Wallisian student was caught speaking their native language in school, they had to wear a tin can lid as a necklace. They also had to write a long French essay over the weekend. This necklace would be passed to the next student caught speaking Wallisian.

Because of French influence, about half of the media on Wallis Island is in French and always available. News and TV shows in Wallisian are often only available once a week, usually at the end of the week. This makes people less likely to watch them, as they might have already seen the news in French. This encourages people to use French more and makes them less interested in learning Wallisian. Some parents even tell their children not to learn Wallisian in nursery and primary schools, saying it's a waste of time.

Wallisian and Futunan Languages

Wallisian and Futunan are two different Polynesian languages. However, they are similar enough that if you know one, it's much easier to learn the other.

Some Wallisians think their language is better than Futunan. They might say Wallisian is easy, but Futunan is hard to pronounce. These ideas came about because Wallis Island was chosen as the main administrative center for the French and the Catholic bishop. Wallis Island received more benefits from France. This made Wallisian more important than Futunan, especially since Futuna Island had fewer educational resources in the 1990s. A well-educated person from Futuna is usually expected to speak three languages: French, Futunan, and Wallisian. By knowing all three, a Futunan can keep their Futunan pride and also have better chances for jobs and education on Wallis Island.

The Language Debate: Church vs. Government

The people of Wallis and Futuna became very close to the Catholic missionaries. The missionaries stayed, learned the local languages, and started schools. They encouraged young men to become priests. However, the islanders did not have a good relationship with French government officials. These officials usually stayed for only two or three years before moving. Because of this, they rarely learned the local languages.

This difference between the church and the government was also seen in France. French politicians and church officials often disagreed. The church did not see a strong reason to force the French language on the islanders. But the French government in Paris wanted the islands to learn French. They made an agreement: French would be taught two hours a day, four times a week, as long as it didn't interfere with Catholic studies.

In 1959, when Wallis and Futuna became a French overseas territory, the education system changed a lot. The Catholic church lost control of the schools. French politicians sent French teachers from France to teach French on the islands. Most of these teachers had little experience teaching French as a second language. This change led to a split in language use: younger people became bilingual, while older people knew very little French. Like the administrators, French teachers also usually stayed for only two or three years.

When these French teachers returned to France, they often said that teaching French on the islands was not very useful. They felt that few people saw the need for the locals to become fluent in French. As debates continued about how the people should be educated, Wallisians realized how important their language was to their culture. They wanted to protect it. They tried to make the language more standard, created social media and entertainment in Wallisian (even though most media came from France), and made Wallisian a school subject.

When French missionaries arrived in 1837, bringing the Latin language, the islanders worried about losing their Wallisian culture. They started Wallisian classes for middle school children. In 1979, when the community got radio transmitters, they began running radio channels specifically in Wallisian.

|

See also

In Spanish: Idioma walisiano para niños

In Spanish: Idioma walisiano para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |