Warangesda Aboriginal Mission facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Warangesda Aboriginal Mission |

|

|---|---|

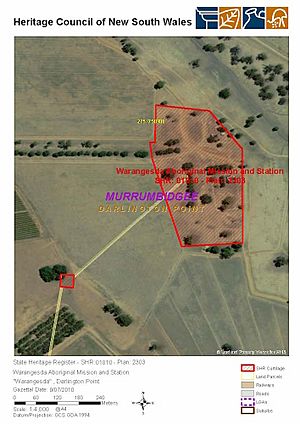

Heritage boundaries

|

|

| Location | Warangesda, Darlington Point, Murrumbidgee Council, New South Wales, Australia |

| Built | 1880–1926 |

| Architect |

|

| Official name: Warangesda Aboriginal Mission and Station; Warangesda Mission; Warangesda Aboriginal Station; Warrangesda | |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 9 July 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1810 |

| Type | Mission |

| Category | Australian Aboriginal |

| Builders |

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Warangesda Aboriginal Mission was a special place in New South Wales, Australia. It was a former Aboriginal mission site near Darlington Point. A mission is a settlement where people, often missionaries, try to help and teach others, sometimes about their religion. This site was designed and built between 1880 and 1926. It is also known by names like Warangesda Aboriginal Mission and Station or Warrangesda. It is now a protected heritage site, added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register in 2010.

Contents

The Story of Warangesda Mission

Life Before Europeans Arrived

Long ago, the area around Warangesda was home to the Wiradjuri people. They didn't live in one place all the time. Instead, they moved around to find food and hold special ceremonies. They gathered plants, fruits, and nuts. Women carried small grindstones to prepare food. Men hunted animals like kangaroos. They cooked food in earth ovens, which were shallow holes in the ground. Traces of these ovens have been found, showing that some traditional ways continued even when the mission was there.

European Settlers and Changes

Around 1832, the first European settlers arrived near Darlington Point. Soon, many Irish settlers took over the land along the Murrumbidgee River. This changed life for the Wiradjuri people. Their food sources were affected, and new diseases spread.

At first, the Wiradjuri and settlers got along. But during a big drought in 1838, things became difficult. Some settlers attacked Aboriginal people. The Wiradjuri fought back, but a sad event happened in 1841. Settlers trapped a Wiradjuri group on an island, and many people died. This ended the organized resistance in the area.

Life became harder for the Wiradjuri. They often depended on settlers for food and work. Some settlers welcomed them for cheap labor, while others were hostile.

Reverend John Gribble Starts the Mission (1879-1884)

John Brown Gribble was a missionary who wanted to give Aboriginal people a permanent home. He founded Warangesda, which was meant to be a farming community. By the 1870s, many Wiradjuri worked for settlers or received handouts. Men earned money by shearing sheep or hunting rabbits. Women worked as domestics.

Gribble traveled to the Riverina area in 1878 and saw that Wiradjuri people were struggling. He remembered a time as a child when an Aboriginal woman cared for him. This memory inspired him to start missionary work.

In 1880, Gribble arrived at a piece of land near the Murrumbidgee River. He was allowed to set up a mission and a school for Aboriginal children. The name "Warangesda" was chosen carefully. "Warang" is a Wiradjuri word for "camp," and "esda" comes from "Bethesda," meaning "house of mercy." So, it meant "Camp of Mercy."

Some local people didn't want the mission there. Gribble saw the mission as a way to protect Aboriginal women.

By the end of 1880, seven houses were built inside the mission, which was fenced. There were 42 Aboriginal residents, and most attended the school. Aboriginal men did all the building work. An old picture shows what Warangesda looked like then.

Over the next two years, the mission grew. Gribble described it as a "township" with his home, a schoolhouse (which was also the church), cottages for families, a home for girls, a hut for single men, and other buildings.

A separate dormitory for girls was set up by 1883. Mrs. Gribble supervised it, caring for mothers with young children, single women, and girls. Girls learned housekeeping skills to prepare them for work. People came from many places to live at Warangesda. They formed a strong community. Even though they adopted European ways like farming and Christian beliefs, their Aboriginal culture continued to be important.

Sometimes, traditional Aboriginal life continued. One year, the manager noted that Aboriginal people had a dance. Another time, men went to a corroboree (a traditional gathering with dancing and singing) to help raise money for a hospital. Hunting and fishing also continued to provide food.

Gribble believed that farming was the best way for Aboriginal people to live. But when food was short, Aboriginal men used their hunting skills. Once, they brought back half a ton of fish using traditional methods.

Gribble's time at Warangesda was challenging. He wanted to help, but there were misunderstandings between the cultures. The mission was managed by white people, and children were often separated from their families in dormitories.

By the early 1900s, English had mostly replaced the Wiradjuri language. Flour and tea became common foods. A photo from the 1890s shows Wiradjuri people at the mission church, dressed in European clothes, looking confident.

After four years, Gribble left Warangesda due to stress. He went on to start other missions in Western Australia and Queensland. He was known as the "Blackfellows' Friend."

Mission Under Government Control (1884-1924)

In 1884, the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Association took over the mission. The government also helped fund it. Warangesda continued as a self-sufficient "Aboriginal station." By 1891, much of the land was cleared for farming wheat.

A visitor in 1908 described the mission: it had a church, school, superintendent's house, about 20 cottages for Aboriginal people, and a girls' dormitory. The station had sheep, horses, and cattle. About 70 Aboriginal residents lived in the neat cottages, but sometimes nearly 300 people were there. The mission was mainly a home for women, children, and older men. Young, able-bodied men were encouraged to find work outside the mission. Men worked on the farm and repaired buildings, earning a small wage and weekly food. They also earned money by trapping animals for their skins.

However, things changed. By 1916, the manager asked for a pistol and handcuffs, showing growing tensions. Many men were later forced to leave Warangesda, and many children were taken to institutions.

By 1924, the population at Warangesda was so small that the government decided to close it. The land was given back to the Lands Department. Within ten years, the people of Warangesda were gone, their belongings auctioned off, and the land offered to new settlers. Most residents moved to camps along the river or to a nearby reserve.

The closure of Warangesda had a big impact. Isobel Edwards, who was born at the mission in 1909, remembered it as a "golden age." She described it as a beautiful little village with two streets, a school, houses with gardens, and shops. She said the government supplied everything, and they were well-off. There was a big pepper tree with a swing where children played. The church was always full on Sundays.

Different managers ran the mission. Some were kind, others were not. Some pulled down fences, ruining gardens. Some expelled young people for no reason. Isobel remembered buying treats for a penny at small shops run by old men. She said the mission broke up when everyone moved away.

Life at the mission was not always easy. In 1886, many adults and children died from measles and diphtheria. White people also got sick. Crowded conditions and food shortages made health worse. A government official in 1891 noted that wind blew through the girls' dormitory walls, causing many colds. He suggested improvements. Later that year, a typhoid epidemic killed several people, including a manager and six children from one family.

Despite these challenges, Warangesda became a strong community. People there were sometimes called "the aristocrats" of Aboriginal communities by local Europeans. It was a largely self-sufficient reserve with up to 150 people.

From 1909, new laws aimed to move Aboriginal people off reserves and into white communities. The government started expelling young men and light-skinned people. Children were sent to institutions.

By 1920, 41 men had been expelled, and over a third of the children were in institutions. Some families left to protect their children. When Warangesda closed in 1924, it was a shock. An old man named Jim Turner, who had helped found the mission and worked there for 45 years, refused to leave. He stood defending his home with a shotgun, but they pulled his roof down around him. He stayed in the ruins until 1930.

The closure of Warangesda forced communities to resettle in other camps and reserves. This was part of a larger trend where other big reserves in NSW were also closed.

Warangesda's Legacy: Founding Other Communities

The people who left Warangesda went on to create or strengthen other Aboriginal communities. These groups developed unique identities. Many Aboriginal families in Narrandera today can trace their family ties back to Warangesda Mission.

- Narrandera Sandhills Community: After Warangesda closed in 1925, many families moved to a former coach stop outside Narrandera and set up the Sandhills community camp. This was the largest community camp in Narrandera.

- Hill 60 Community (Narrandera): Some Aboriginal families from Warangesda and Narrandera began buying land at Hill 60 as early as 1933. It became a busy Aboriginal settlement in the 1940s.

- Darlington Point Reserve and Town Community: Even while Warangesda was open, some people camped on the riverbank nearby. After the mission closed in 1925, many moved to the Darlington Point reserve.

- Erambie Reserve, Cowra: The Aboriginal population in Cowra grew in the early 1920s, partly because people were leaving Warangesda.

What Remains at Warangesda Today

The mission site is now part of a private farm called Warangesda station. You can still find ruins of four buildings and other old remains from the mission period. There are also two surveyed cemeteries. A third cemetery is thought to exist but hasn't been found yet. Outside the main site, there's a row of pepper trees that used to be a long avenue leading to the mission.

The mission was planned like a formal village. Aboriginal houses were in a line, and the church and flagpole were in the center. Other buildings like the school and girls' dormitory were around the edges. The church was the most important building at first.

Remaining Buildings and Structures

By 1993, only four buildings were left. Many earth banks were built over the years to protect the mission from floods. These banks and other small signs on the ground help us understand where buildings once stood. Most of the remaining structures were built when the Aborigines Protection Board ran the mission. These include earth banks, the schoolhouse, the teacher's cottage, the girls' dormitory, and the ration store, all of which are now ruins.

Mission Church Site

The mission church stood for about 100 years. By 1980, it was a ruin used as a barn, and in the mid-1980s, it burned down. Now, it's just a low mound with some burnt wood pieces. Items from the church, like the baptismal font and organ, are now in museums or other churches nearby. The church bell, lectern, and bible were moved to the Church of England at Darlington Point.

School House

The schoolhouse was updated in 1910. It later became a shearing shed for the farm in 1941. This changed its structure quite a bit, adding new walls, doors, and equipment for shearing sheep.

Girls Dormitory

A children's dormitory was used by 1887. The current building was likely built in 1896. To the west of the dormitory was a house believed to be the manager's house. When Stewart King leased the farm, the dormitory became his first home. He made changes to it, including removing the old manager's house.

Ration Shed

This building has completely fallen down and is now just a pile of wood.

Other Old Buildings

Other old buildings from different times of the mission are now ruins or archaeological sites. Digging there would help us learn more. Many items found relate to the mission period, even if they were later used for the farm.

Teacher's Cottage

Aboriginal mission residents helped build the first schoolmaster's hut. The teacher's cottage was repaired in 1897 and later became a workshop in 1907. In 1940, it was turned into shearers' quarters. Many items found in the building today are from this shearing time.

Cemeteries

There are two cemeteries at Warangesda. One was for children and is inside the mission block. The other was for adults, a short distance from the houses. Both are marked by trees. The Mission Cemetery has one headstone, and the Children's Cemetery has one grave marked by a metal fence.

Old Objects and Archaeology

Many old farm tools and other items were found scattered around the buildings in 2009. These include horse harnesses, parts of old machinery like a horse-drawn harvester, and pieces of a buggy.

From the schoolhouse, small pieces of children's slates and parts of ink-pots were found. In the old ration store, a meat saw was found, showing it was once a butcher's shop. Parts of beds from the girls' dormitory were reused as gates and animal pens around the site.

Older handmade tools also date from the mission period. Changes after the mission closed are also seen in the objects. For example, the schoolhouse became a shearing shed, and shearing equipment was found there.

A large area to the north has many scattered household items. This might be where families had their huts or where mission rubbish was dumped.

Condition of the Site

As of 2009, the ration store had completely fallen down. The girls' dormitory and schoolhouse had damaged roofs and collapsing walls. The teacher's cottage was in the best condition, still having its roof and walls.

Storms, fire, and farming activities have affected the site. Only four buildings remain, and they are in ruins. However, there is a lot of archaeological evidence that helps us understand the different stages of the mission's history.

Important movable objects from Warangesda, like stone tools from before Europeans arrived and mission items, are now in collections at the Anglican Church in Darlington Point, the Pioneer Park Museum in Griffith, and the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. Some old writings from Warangesda are in the National Library of Australia.

Changes Over Time

The site changed in clear stages:

- The original Christian mission (1880-1884)

- The government-run Aboriginal Station (1884-1926)

- The King family farm (1927-1957)

- Continued farming by the King family's descendants (1957 to today)

Why Warangesda is Important

The Warangesda mission site is very special because it has rare ruins and archaeological remains. These show how Aboriginal culture changed and how the fight for Aboriginal land rights developed. The site gives us a unique look into how a Christian mission and Aboriginal station were planned and grew in New South Wales in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Warangesda is historically important for how it affected Indigenous Australians and how they adapted over generations. It was also a place of early political action, including an Aboriginal community strike in 1883. The site is important because it helped found or grow other Aboriginal communities, like those in Narrandera, Darlington Point, and Cowra.

Warangesda Mission is very important to the Aboriginal communities of Narrandera, Darlington Point, and Cowra, who have strong family connections to the place. It is a "heartland" for many important Aboriginal family networks in southeastern Australia, including the Bamblett, Howell, Atkinson, Kirby, Murray, Charles, Little, and Perry families. Thousands of Aboriginal people today are descendants of Warangesda residents.

The Aboriginal people at Warangesda were a relatively self-sufficient community. They helped the local economy by providing labor for farming. They also kept their distinct Aboriginal lifestyle and strong family connections across the region.

Warangesda is rare because it is one of only ten missions ever set up in New South Wales. It is unique because it is the only mission or reserve site in NSW that still has original 19th-century building ruins and archaeological remains. The site is also linked to the last big burbung (a traditional initiation ceremony) in Wiradjuri country, held near Warangesda in the 1870s.

The Warangesda Mission girls' dormitory was important because it became the model for the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls. This Cootamundra Home was a key place where Aboriginal girls from all over NSW were taken from their families for training. These girls are part of what is known as the "Stolen Generations".

Warangesda is connected to Reverend John Brown Gribble, an important historical figure who, with his wife and the help of Aboriginal people, built the mission. Other important people connected to Warangesda include political activist William Ferguson, country musician Jimmy Little, folk singer Kaleena Briggs, and artist Roy Kennedy, who has many artworks about Warangesda.

The archaeological remains at Warangesda show the many stages of development at an Aboriginal settlement from 1880 to today. Warangesda has burials in at least two cemeteries: one for infants and one for adults.

Warangesda Aboriginal Mission was officially listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 9 July 2010.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |