Waxy corn facts for kids

Waxy corn or glutinous corn is a special type of field corn. When you cook it, it becomes sticky, much like sticky rice. This happens because it has a lot of a starch called amylopectin.

This unique corn was first found in China in 1909. For a long time, American plant breeders used it to help them find hidden genes in other corn types. In 1922, a scientist discovered that waxy corn has only amylopectin starch, unlike regular corn which has two types of starch.

Before World War II, the main source of this sticky starch in the United States was tapioca. But when supplies were cut off during the war, people started using waxy corn instead. Today, amylopectin from waxy corn is used in many food products. It's also used in industries like textiles, adhesives, and paper.

Later, tests showed that waxy corn could help animals gain weight more efficiently than regular corn. This made people much more interested in waxy corn. Scientists learned that waxy corn has a small genetic difference that stops it from making the other type of starch. This difference is controlled by a single gene. Waxy corn usually produces a little less yield than regular corn and needs to be planted at least 200 meters away from other corn fields to keep it pure.

Contents

History of Waxy Corn

We don't know the exact story of how waxy corn first appeared. The first records of it are from the USDA.

In 1908, a missionary named Rev. J. M. W. Farnham sent some seeds from Shanghai, China, to the U.S. He wrote a note saying it was "A peculiar kind of corn" that was "much more glutinous" (sticky) than other types. He thought it might be useful, perhaps for porridge.

These seeds were planted in 1908 near Washington, D.C. by a botanist named Guy N. Collins. He grew 53 plants and carefully described them, even taking photos. His findings were published in a USDA report in 1909.

Later, waxy corn was found again in Upper Burma in 1915 and in the Philippines in 1920. A researcher named Kuleshov also found it in many other parts of Asia.

Some people wondered if corn was known in Asia before Christopher Columbus discovered America. Most experts, like De Candolle in the late 1800s, believed corn came from America and was only brought to the Old World after the New World was discovered.

But finding this unique waxy corn in China made some people rethink this. The Portuguese arrived in China in 1516, bringing corn with them. Collins thought waxy corn might have appeared as a new type (a mutation) in Upper Burma. Some scholars found it hard to believe that American corn could spread so far, mutate, and then spread from the Philippines to Northern Manchuria in just a few hundred years.

Today, we have answers to these questions. First, we know that the waxy mutation is actually quite common. Second, corn was likely accepted quickly in Asia because it met a great need, much like potatoes did in Ireland.

Historians say that corn was first clearly described in Chinese records around the 1500s. While some think corn might have reached Asia before 1492, there's no solid proof like old plant pieces or writings. So, the idea that corn came from America and was introduced to the Old World after 1492 is still widely accepted.

Collins noticed that this new Chinese corn had several special features. It could resist dry, hot winds during flowering, which helped it grow. Even though its ears were small, this special ability made it useful, especially in dry areas. So, people tried to mix its good traits with those of larger, more productive corn types.

Collins also suspected a chemical difference in the waxy corn's kernels, even though initial tests showed normal amounts of starch, oil, and protein. He was very interested in the starch's physical nature. He wrote that its unique starch might be important for food. For many years, waxy corn was mainly used as a "genetic marker" in corn breeding. Breeders used its special traits to track hidden genes. Without this, waxy corn might have disappeared in the USA.

In 1922, another researcher, P. Weatherwax, found that the starch in waxy corn was entirely a "rare" form called amylopectin. He noticed it stained red with iodine, while normal starch stained blue. Other scientists later confirmed this.

Just before World War II, in 1937, plant breeders started trying to put the waxy trait into high-yielding hybrid corn. By this time, the waxy corn no longer had all the unusual features Collins first noted; only its unique starch remained. At this point, waxy corn wasn't very important because the main source of pure amylopectin was still the cassava plant.

During World War II, when Japan cut off supplies to the U.S., companies had to switch to waxy corn. It was perfect because it could be processed using the same machines as regular corn. In 1942, about 356 metric tons of waxy corn were produced in Iowa for industrial use, growing to 2540 tons in 1943. By 1943, about 81,650 tons of waxy corn were grown to meet the demand for amylopectin. From World War II until 1971, all waxy corn in the U.S. was grown under special contracts for food or industrial companies. Most of it was grown in just a few counties in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana.

In 1970, a serious corn disease called Southern corn leaf blight spread across the U.S. corn belt. Most corn grown then was vulnerable to this disease. Farmers urgently needed corn that could resist the blight. Some waxy corn seeds ended up on the market because they had the right kind of plant material to resist the disease.

Some farmers who fed this waxy corn to their cattle noticed the animals grew well. More feeding tests showed that waxy corn helped animals gain weight more efficiently than regular corn. This made waxy corn much more popular, changing it from a scientific curiosity to an important research topic.

In 2002, about 1.2 to 1.3 million tons of waxy corn were produced in the United States. This was grown on about 2,000 square kilometers, which was only about 0.5% of all corn production.

What Makes Waxy Corn Special?

Chinese Corn Traits

When Collins studied the Chinese waxy corn, he noticed several unusual things:

- It had special parts that helped it survive dry, hot winds when it was flowering.

- Its top four or five leaves all grew on the same side of the stem, and the upper leaves stood very straight up.

- One of the most important things he noticed was the inside of the corn kernels, called the endosperm. He wrote that its texture was like "the hardest waxes." This is why it's called "waxy" corn. You can only see this waxy trait clearly when the kernel's moisture is 16% or lower.

Regular corn starch usually has about 25% amylose and the rest is amylopectin. But waxy corn contains 100% amylopectin. This is important because it's very expensive to separate amylose and amylopectin from regular starch.

Genetics of Waxy Corn

Scientists have studied the genes of waxy corn. The waxy trait is caused by a single gene (called wx) located on chromosome 9. This gene controls the waxy endosperm in the kernel. The normal gene (Wx) makes regular starch.

The waxy trait in corn is similar to the "glutinous" (sticky) trait found in waxy rice, sorghum, millet, barley, and wheat. These plants also have starch that stains red with iodine.

If you cross two waxy corn plants that carry both the normal and waxy genes, you'll get a mix of waxy and non-waxy kernels. Scientists can even tell which pollen grains carry the waxy gene by staining them with iodine. Half will be blue (normal) and half brown (waxy).

The waxy gene is not rare. It has appeared many times in different corn varieties.

How Waxy Corn is Grown

Growing waxy corn for industrial use needs special care compared to regular corn.

It's fairly easy to breed new waxy corn varieties by mixing them with regular corn. However, waxy corn usually produces 3% to 10% less yield than regular corn.

Because the waxy gene is recessive (meaning it only shows up if both genes are waxy), waxy corn fields must be planted at least 200 meters away from any regular corn fields. This stops pollen from regular corn from mixing with the waxy corn. Even a few regular corn plants growing from last year's seeds can contaminate a whole waxy corn field, making the kernels regular instead of waxy.

Almost all waxy corn is grown under special contracts for companies that process starch. Farmers get extra money for growing it. This helps cover the lower yield and the extra work needed to make sure the corn is not contaminated.

What Waxy Corn is Used For

Amylopectin from waxy corn is easy to thicken. It creates a clear, thick paste that feels sticky. This paste is similar to those made from potato or tapioca starch. Waxy starch also stays thick better and doesn't become watery as easily as regular corn starch. These differences make it useful in many ways.

Food Products

Special waxy corn starches are used to make many food products better. They improve how uniform, stable, and textured foods are. Because it's clear and stays thick, waxy starch is great for thickening fruit pies. It makes canned foods and dairy products smoother and creamier. It also helps frozen foods stay good after freezing and thawing. It gives dry foods and mixes a better texture and look. Waxy corn starch is also preferred for making maltodextrins, which dissolve better in water.

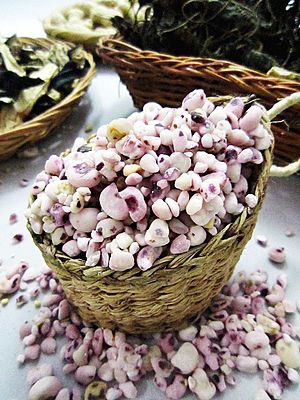

Waxy corn on the cob is very popular in China and Southeast Asia. You can often find it frozen or pre-cooked in Chinatowns. It's the most popular corn in China for eating fresh. People in East Asia like its sticky texture because they are used to similar foods like tapioca pearls, glutinous rice, and mochi.

Adhesive Industry

Waxy corn starch is different from regular corn starch in its structure and how it thickens. Pastes made from waxy starch are long and sticky, while regular corn starch pastes are short and thick. Waxy corn starch is a main ingredient in glues used for bottle labels. This waxy starch glue helps labels stay on bottles even when wet or in humid conditions. Waxy corn starches are also commonly used in the U.S. for making gummed tapes and envelope glues.

Animal Feed Research

Research into feeding waxy corn to animals started in the 1940s. Studies suggested that waxy corn could help animals convert feed into weight more efficiently than regular corn. Many feeding trials showed a small to clear benefit. For example, it led to more milk and butterfat in dairy cows, and better daily weight gains in lambs and beef cattle.

However, despite all this research, waxy corn didn't become widely used in the animal feed industry. Scientists found that how easily starch is digested depends on more than just being amylopectin. It might also depend on the structure of the starch granule itself and how the starch molecules are linked together.

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |