Whitechapel Mount facts for kids

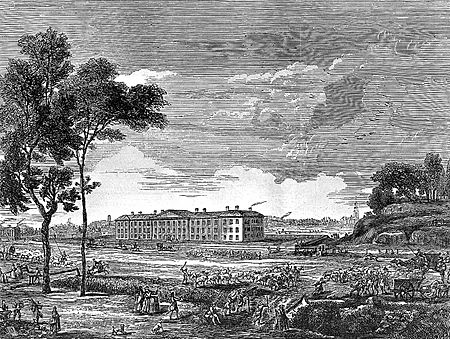

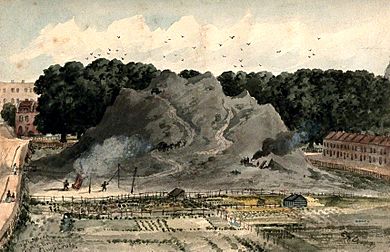

Whitechapel Mount was a huge hill made by people a long time ago. Nobody is completely sure why it was built! It was a very famous landmark in London during the 1700s. The Mount stood on Whitechapel Road, right next to the new London Hospital. It was much older and taller than the hospital.

People used tracks to go up the Mount. It was a great spot for looking out over the city. Sometimes, people even hid stolen items there! Horses and carts could climb it, and it had some trees and houses on its sides. People had many ideas about where it came from:

- It might have been a fort built during the English Civil War.

- It could have been a burial place for people who died in the Great Plague.

- It might have been a pile of rubble from the Great Fire of London.

- It could have been a laystall, which was a big rubbish dump (that's why it was sometimes called Whitechapel Dunghill).

It's possible that all these ideas are a little bit true! Whitechapel Mount was taken down around 1807. Many Londoners thought it was made of rubble from the Great Fire. So, people who liked old things searched through its remains, and some exciting discoveries were claimed. Today, its name lives on in places like Mount Terrace in London.

Contents

Where Was Whitechapel Mount?

The Area Around the Mount

Whitechapel Mount was on the south side of Whitechapel Road. This road was an old path leading from the City of London to places like Mile End, Stratford, and Colchester. In the 1700s, the area around the Mount was mostly open fields. These fields were used for grazing cows or for growing vegetables.

If you left London and traveled east, you would pass the church of St Mary Matfelon (which gave Whitechapel its name). Then you would see a windmill before reaching the Mount. Across Whitechapel Road, there was a burial ground and a pond. Further east, the road changed its name to Mile End Road.

According to John Strype in 1720, the area was busy. Whitechapel had good inns for travelers, and Mile End had nice houses for sea captains. However, Strype also said that Whitechapel Road was crowded with poorly built houses.

The area could be dangerous for travelers. There were reports of crimes and robberies. Sometimes, stolen items were even buried in Whitechapel Mount and later found there. It was also a place where people gathered for rough activities.

From the top of Whitechapel Mount, you could see far across the area. You could see the small towns of Limehouse, Shadwell, and Ratcliff.

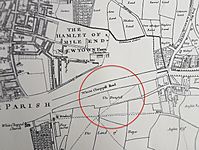

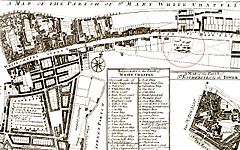

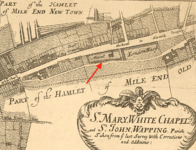

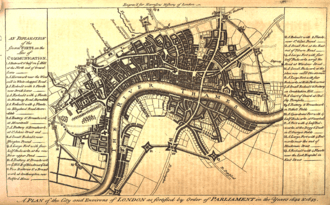

Whitechapel Mount on Old Maps

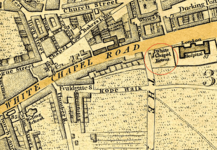

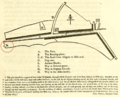

The first time Whitechapel Mount appeared on a map was in 1673. Sir Christopher Wren drew it as part of a building plan. He called it "the mud wall called the Fort." In Joel Gascoyne's map from 1703, it was called The Dunghill. This map showed it was at least 400 yards long. It even had a path and a road crossing it.

On John Rocque's map of London from 1746, the Mount looked like a very tall hill. It had at least one house, maybe even a row of houses, on its western side. Richard Blome's map from 1755 showed a large house with a driveway next to the newly built London Hospital. In John Cary's 1795 map, part of the Mount was cut off by a new road. It still looked like it had a large building on its northwest corner.

What Was Whitechapel Mount's Origin?

Civil War Fortification Theory

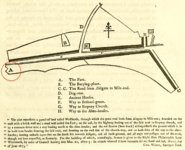

In 1643, London quickly built defenses against the Royalist armies. People were worried that Prince Rupert would attack the city. So, a large ditch, an earth wall, and strong forts had to be built.

About 23 or 24 earth forts were built around London and its suburbs. These forts were close enough that you could see one from another. Volunteers, like older men, guarded these forts. Local innkeepers had to provide them with food.

The forts were connected by an earth bank and a trench. Many people helped dig these, including "great numbers of men, women and young children." People from all parts of society joined in the work:

From ladies down to oyster-wenches

Labour'd like pioneers in trenches,

Fell to their pick-axes and tools,

And help'd the men to dig like moles.

The complete ring of defenses was 18 miles long. A visitor from Scotland walked it, and it took him 12 hours.

Fort No.2 was designed to protect Whitechapel Road. The Scottish traveler described it as a "nine angled fort." It had wooden fences and a single ditch. It also had seven brass cannons and a guardhouse made of wood. There was a trench around its base.

Daniel Lysons said the earthwork at Whitechapel was 329 feet long. It was 182 feet wide and more than 25 feet above the ground.

After the Civil War, these forts were quickly removed. They were on valuable farmland. However, some traces remained, and Whitechapel Mount was one of them. Lysons wrote in 1811 that the east end of the Mount was still very clear. Houses had been built on the west side. The top of the Mount was flat. Mount Street, Mayfair, is another place name that comes from one of these Civil War forts.

Great Plague Burial Ground Theory

In 1665, a terrible disease called the bubonic plague spread through London. It's estimated that 70,000 to 100,000 Londoners died. Areas like Aldgate, Whitechapel, and Stepney were hit very hard. This put a lot of pressure on places to bury the dead. Some people were buried in large mass graves.

Official mass graves were deep pits left open until they were full of bodies. People who moved the dead were not always careful. One person at the time said they were "very idle base liveing men and very rude." They would draw attention to their work by swearing.

No old records officially confirm that bodies were buried in Whitechapel Mount. We know there were other burial grounds or plague pits nearby. For example, there was one across the road. Whether the Mount itself was used for burials is still debated. However, popular stories said it was. One story claimed that rubble from the Great Fire of London was thrown over a plague pit to cover it up.

When people planned to remove Whitechapel Mount, authorities denied these rumors. They even had the Mount "pierced" (dug into) to try and prove the rumors wrong.

The clearest reliable source is Joseph Moser. He wrote in 1802 that when part of the Mount was being removed, he saw many human bones. He also saw animal bones, bricks, and tiles. He said the bones were in a sticky, bluish earth, which was the original ground. This suggests it was used for burials. Also, a history of the London Hospital says that by 1764, "The Mount Burying Ground was full." This suggests the hospital might have used the Mount for burials too.

Great Fire Rubble Theory

The Great Fire of London happened the year after the plague. The closest area that burned was about a mile away from Whitechapel Mount. Even so, respected people, like Dr. Markham, the rector of Whitechapel Church, believed the Mount was made or added to with rubble from the Great Fire. He even investigated it carefully. This idea was widely believed, though some people disagreed. When the Mount was taken apart in the 1800s, many people who liked old things came to search for treasures.

Laystall (Rubbish Dump) Theory

The ideas above might not fully explain how huge Whitechapel Mount was. Its size is clear from old maps and pictures.

A laystall was an open rubbish dump. Towns used them to get rid of garbage until modern landfills in the 1900s. In October 1671, seven laystalls were set up for the City of London. All street sweepings and household rubbish had to be taken to one of these places. Whitechapel Mount was one of them. It was supposed to receive rubbish from several areas of London.

But a laystall was more than just a dump; it was a business. The owner hired groups of men, women, and boys to sort the rubbish and recycle it. Without them, people would just dump trash anywhere. William Guy, who studied London's laystalls in the mid-1800s, reported:

In most of the laystalls or dustmen's yards, every species of refuse matter is collected and deposited:– nightsoil, the decomposing refuse of markets, the sweepings of narrow streets and courts, the sour-smelling grains from breweries, the surface soil of the leading thoroughfares, and the ashes from the houses. The proportion in which these several matters are collected, vary... In all these establishments the bulk of the deposits consists of dust from the houses, which is sifted on the spot by women and boys seated on the dust-heaps, assisted by men who are engaged in filling the sieves, sorting the heterogeneous materials, or removing and carting them away.

The law mentioned "dung, soil, filth and dirt." However, most household rubbish was coal ash. This is why people called them "dustmen." This ash could be used to make bricks. In the late 1700s, there was a huge need for bricks to build the growing city of London. There were many brick-making areas nearby, like at Mile End. A court case from 1809 shows that bricks were being delivered from the shrinking Whitechapel Mount.

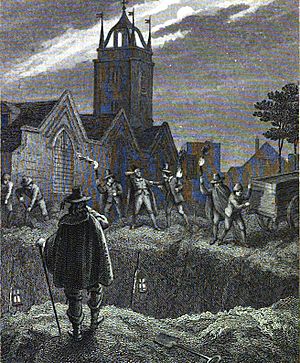

Removing Whitechapel Mount

When the East and West India Docks were built in the early 1800s, new roads were needed. These roads went through the low, wet fields from Shadwell to Whitechapel. A new road, Cannon Street Road, went from Whitechapel Mount to St George in the East. This road made the land around it much more valuable. So, the City of London decided to remove the Mount. This happened in 1807–1808. Mount Place, Mount Terrace, and Mount Street were then built on the same spot.

The process of removing the Mount took several years. At first, efforts were slow. There was even an idea to build a canal from Paddington to the docks at Wapping by going through Whitechapel Mount.

The soil from the Mount was used to make bricks. These bricks were used to build places like Wentworth Street in Bethnal Green and "Hanbury's Brewhouse" (the Black Eagle Brewery). Some of these buildings are still standing today.

Antique Hunters and Finds

Many Londoners believed the Mount contained rubble from the Great Fire. So, lots of excited people came to search through its soil. Various old items were found, or claimed to be found, including a silver cup and a Roman coin. Finding something in the Mount made it seem more special.

The most amazing find was a carved boar's head with silver tusks. Experts said it was a real souvenir from the Boar's Head Inn, Eastcheap. This inn was famous from Shakespeare's plays and was truly burned down in the Great Fire of London.

Whitechapel Mount in Stories and Songs

The Skeleton Witness: or, The Murder of the Mound was a play by William Leman Rede. It was performed in England and America. In the play, a villain commits a murder and hides the body in Whitechapel Mount. The crime is set up so that an innocent hero will be blamed if the body is found. The hero leaves for seven years and becomes rich. When he returns to London, he learns that the Mount will be cleared away the next day. To stop this, he rushes to the Mount's owner and buys it for a huge price. The seller becomes suspicious and sends men to dig around. They find the skeleton. Through a complicated story, the hero proves he is innocent and gets the girl, and they live happily ever after.

The Mount was also used as a way to talk about the far east side of London. For example, people would say "from the farthest extent of Whitechapel mount to the utmost limits of St Giles." Or, "[the news] was all over town, from Hyde Park Corner to Whitechapel dunghill." A popular song from the 1700s called The Coachman began:

I'm a boy full spunk, and my name's little Joe,

It's I that can tip the long trot;

From Whitechapel-mount up to fam'd Rotten-row,

With the ladies sometimes is my lot.

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |