Willamette Falls Locks facts for kids

|

Willamette Falls Locks

|

|

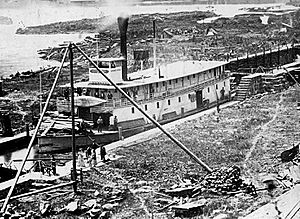

Steamboat and barge traffic in the lock, circa 1915

|

|

| Location | West Linn, Oregon, US |

|---|---|

| Built | 1873 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001680 |

| Added to NRHP | 1974 |

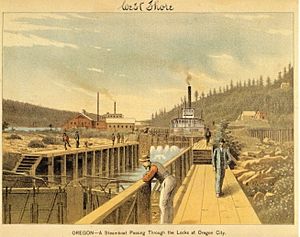

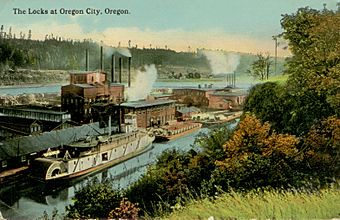

The Willamette Falls Locks are a special system of locks on the Willamette River in Oregon, USA. They opened in 1873 and closed in 2011. These locks helped boats travel past the powerful Willamette Falls and the T.W. Sullivan Dam. Since their closure, the locks are considered "non-operational" and are likely to stay closed forever.

The locks are located in the Portland area, about 25 miles upriver from the Columbia River. They are in West Linn, right across the Willamette River from Oregon City. The United States Army Corps of Engineers used to run the locks, mostly for pleasure boats. It was free for all boats to pass through. The locks were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 because of their historical importance.

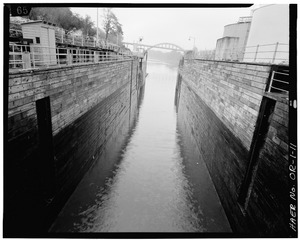

The lock system has four connected chambers with seven gates. These gates could lift boats up to 50 feet (15 m) (depending on water levels). The usable width for boats was 37 feet (11 m). The whole system is 3,565 feet (1,087 m) long and could handle boats up to 75 feet (23 m) long. Each of the four concrete chambers is 210 by 40 feet (64 by 12 m).

Contents

- Building the Willamette Falls Locks

- How the Locks Were Designed

- Building the Locks

- Opening the Locks

- Later Years and Ownership Changes

- Finances and Company Changes

- Flood Damage and Repairs

- Federal Government Takes Over

- Reconstruction (1916–1917)

- Recent Repairs and Closure

- Historic Status

- Images for kids

Building the Willamette Falls Locks

The canal and locks were built between 1870 and 1872. A lot of planning, legal work, and money-raising happened before construction could start. The Willamette Falls Canal and Locks Company was created in 1868. Its goal was to build a way for boats to get around the Willamette Falls.

At that time, one company, the People's Transportation Company, controlled all the shipping around the falls. This gave them a lot of power over river transport. The new canal and locks were built partly to break this company's control and allow more competition.

Getting the Project Started

The Wallamet Falls Canal and Locks Company was officially formed on September 14, 1868. It had a starting capital of $300,000. Key people involved included N. Haun, Samuel L. Stephens, and experienced steamboat captain Ephraim W. Baughman. Their goal was to build a canal and boat locks on the west side of the Willamette Falls.

Government Support for the Locks

On October 26, 1868, the Oregon government passed a law to help fund the canal. They believed it was "of great importance to the people of Oregon" to have these locks. The law gave the company a grant of $150,000. This money would be paid in yearly amounts after the locks were finished.

To get the money, the company had to spend at least $100,000 by January 1, 1871. They also had to complete a working canal and locks on the west side of the falls. The locks had to be strong, made mostly of stone, cement, and iron. They needed to be at least 160 ft (49 m) long and 400 ft (122 m) wide. Once finished, a group chosen by the governor would check if the work met the rules. If not, no money would be paid.

Charging for Passage

The company could charge fees (tolls) for using the locks. For the first ten years, they could charge up to 75 cents per ton of freight and 20 cents per passenger. After ten years, the maximum tolls would drop to 50 cents per ton and 10 cents per passenger. The state of Oregon also had the option to buy the canal after 20 years. The company also had to give 10% of its profits from tolls to the state for the first ten years, and 5% after that.

Changes to the Plan

The first deadline set by the government was too hard to meet. The initial money offered was not enough to attract investors. So, in 1870, a new law was passed. This law increased the government's support to $200,000. This money came in the form of special bonds from the state. The new deadline for finishing the locks was January 1, 1873.

More money was raised by selling company bonds, adding another $200,000. These bonds were sold at a discount. In total, about $315,500 was raised to build the locks and canal.

How the Locks Were Designed

The first plan in 1869 was for a canal 2,500 ft (762 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) wide, with three locks about 200 ft (61 m) long. However, when bids were requested in 1871, the plans changed. They now called for four locks, each 160 ft (49 m) long, with a canal about 2,900 ft (884 m) long. The plan included a wooden wall along the canal and masonry (stone) locks.

Isaac W. Smith became the chief engineer in February 1871. He suggested some changes. He wanted the wooden wall to be replaced with a stone one. He also wanted to make all the locks longer, to 210 ft (64 m). A fifth "guard" lock was also added. Contracts were given out based on these new plans.

However, the contractors struggled to finish the work. In December 1871, Smith reported that he had miscalculated the cost of rock. Stone walls could not be finished by the January 1, 1873, deadline. By May 1872, Smith changed back to using a timber wall, reinforced with iron and stone. This change saved money, but some people criticized it for not meeting the state's original standards.

Building the Locks

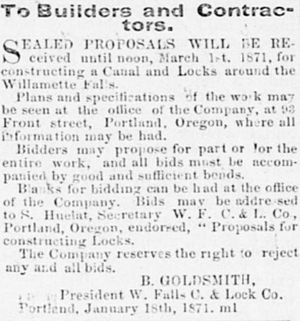

On January 18, 1871, the company asked for bids from contractors. Captain Isaac W. Smith was the main supervisor. The goal was to finish by December 1, 1872. Contractors were paid monthly, with 20% held back until the work was done. By October 1872, the cost was estimated at $450,000, with about $50,000 more needed to finish.

Blasting and Workforce

To cut holes in the rock, they used new steam-powered drills with diamond tips. These drills cut a ring into the rock, making it easier to blast. Blasting had to be done carefully so the broken rock could be used for the stone walls.

Between 300 and 500 men worked on the project, with about 100 working at night. In September 1871, it was hard to find enough workers and stonemasons. Workers were paid about $2 a day in coin, with stonemasons earning more. Masons and stone-cutters earned $5 to $6 a day, carpenters $3 to $3.50, and laborers $2.50. The monthly payroll was $50,000. The project was successful because workers were treated well and paid on time.

Materials Used

The project involved digging out 48,603 cubic yards (37,160 m3) of rock and other materials. They installed a lot of masonry (stone work). A large ditch (gulch) was filled with 20,000 cubic yards (15,000 m3) of stone.

The project used 1,138 lineal feet (347 m) of masonry walls and over 2,200 ft (671 m) of timber walls. They used 18,000 pounds of "giant powder" (dynamite) and 10,000 pounds of black powder for blasting. Other materials included cement, lumber, and thousands of pounds of iron for gates and bolts.

Opening the Locks

The locks were ready for boats on December 16, 1872. However, they needed a few more days to fix some gates. Governor La Fayette Grover appointed three people to check the locks and make sure they were built correctly. They inspected the locks on December 28, 1872.

The small steamer Maria Watkins was the first boat to use the locks. This happened on Wednesday, January 1, 1873, at 12:17 p.m. A large crowd cheered as the boat entered the first lock. The boat blew its steam whistle in response.

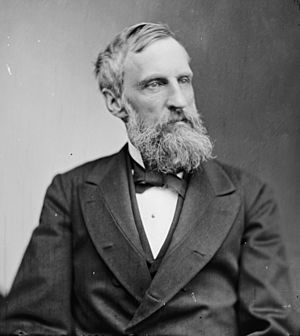

Each lock raised the boat ten feet. After Watkins passed through, Governor Grover congratulated the company president, Bernard Goldsmith. It took one hour and forty-five minutes for Watkins to go through all the locks. The return trip took about an hour. They expected to cut the travel time down to half an hour later.

How the Locks Were Built (1873)

When finished, the canal and locks were 3,600 ft (1,097 m) long. They included:

- An entrance to the first lock, 200 ft (61 m) long and 50 ft (15 m) wide.

- Four lift locks, each 210 ft (64 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) wide.

- A canal section south of the lift locks, 1,273 ft (388 m) long.

- A guard lock, 210 ft (64 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) wide.

- Another canal and basin, 1,077 ft (328 m) long.

The lift locks were "combined" locks, meaning the lower gate of one lock was also the upper gate of the next one. The lock walls were 19 ft (5.8 m) tall above the lock floors. The first and second locks were carved out of solid rock. Wooden fenders were bolted to the sides to protect boats. The fourth lock had masonry walls on both sides.

Each of the four lift locks raised boats by 10 ft (3.0 m). The total drop from the upper river to the lower river was 40 feet. The lower end of the canal was cut 40 ft (12 m) deep through solid rock.

Gate Design

The gates were designed to swing easily, operated by one person. Each gate had eight "wickets" (small openings) near the bottom. These wickets were used to fill and drain the locks. Two men were needed to operate each gate. Each lock gate was 22 ft (7 m) long and 20 ft (6 m) high.

The stone used for the walls was local basalt. The walls were built with large basalt blocks, each weighing 1 to 2 tons. When completed, the maximum water depth in the locks was 3 ft (0.9 m). This was enough for riverboats to pass safely.

Later Years and Ownership Changes

The stone parts of the locks were expected to last a very long time. The wooden parts, however, were expected to last about eight to ten years. After the locks opened, more construction work was still needed for several months.

The annual cost for repairs was expected to be low, around $600. The locks needed a superintendent and two lock-tenders. Some people believed the locks helped keep railroad shipping prices fair by offering competition.

New Owners Take Over

On December 28, 1875, a new company called the Willamette Transportation and Locks Company was formed. On March 8, 1876, the original company sold all its property, including the canal and locks, to this new company for $500,000.

By 1877, important businessmen like John C. Ainsworth and Simeon G. Reed were involved with the new company. This company also owned and operated steamboats on the Willamette River. By 1880, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (O.R.&N) controlled the Willamette Transportation and Locks Co.

Tolls and Management

Oregon laws in 1876 and 1882 created a special commission to oversee the canal. This commission could check the locks and make sure they were maintained. Boats using the canal had to report how much freight and how many passengers they carried.

The first lock tender was John "Jack" Chambers, who worked at the locks for 50 years. He was well-known to all steamboat captains. The initial tolls were 50 cents per ton of freight and 10 cents per passenger.

Even though the law said the company should send 10% of its profits to the state, only one payment was made in 1873. The company claimed there were no profits after that. In 1905, the state sued the Portland General Electric Company (the new owner) to get its share of the tolls. However, a court ruled in 1906 that the law only applied to the original company, not its successors.

Finances and Company Changes

In 1887, the Willamette Transportation and Locks Co. took out a loan of $420,000. In 1889, the company allowed two industrial firms to use water from the canal for their factories. To do this without stopping boat traffic, an extra channel was built to fill the canal.

On August 8, 1892, the Portland General Electric Company was formed. One of its goals was to own and operate the Willamette Falls Canal and Locks. On August 24, 1892, the Willamette Falls and Locks Company sold all its property, including the canal and locks, to Portland General Electric.

Oregon had the chance to buy the locks and canal in 1893, 20 years after they were finished. But the state never did. The average income from tolls between 1887 and 1892 was about $15,750 per year. After expenses, this was a small return on the $450,000 it cost to build the locks. By 1908, Portland Railway, Light and Power Company owned Portland General Electric.

Flood Damage and Repairs

A big flood in 1890 badly damaged the locks. The canal filled with debris. Two lock gates were destroyed, and the lock tender's home was ruined. More repair work was planned for 1893, expected to cost between $135,000 and $150,000.

This planned work included making 1,300 feet of the canal wider (to 80 feet). They also planned to replace a rotting wooden wall with a stronger stone one. A wider canal would allow steamboats to pass each other more easily. It would also hold more water for factories and navigation. The lowest lock was also to be deepened so larger steamboats could pass safely during low water.

Federal Government Takes Over

On March 3, 1899, a group of United States Engineers looked at the locks. They wanted to see if the U.S. Government should buy them. By 1899, the wooden lock gates were old and leaking badly. Most of the wooden parts needed to be replaced soon.

Study by Engineers

In 1899, it would have cost about $38,800 to fix the locks and make them work like new. The total value of the project in 1899 was estimated at $314,300. The Corps of Engineers thought the locks were worth about $421,000.

The report suggested buying the locks if the price was fair. However, the owners wanted $1,200,000, which the government thought was too high. By 1899, the locks were in poor condition. Also, so much water was used by factories that it made it hard for boats to use the locks.

Between 1882 and 1899, the locks were used over 12,800 times. They carried over 234,000 passengers and 504,000 tons of freight.

Steps to Buy the Locks

In June 1902, Congress allowed a study to see if the U.S. government should buy the canal and locks. The main problem with buying the locks was the "water rights." Factories near the falls used water from the canal for power. They used so much water that during low river levels, factories and boats couldn't operate at the same time. The U.S. government only wanted to buy the locks if there was enough water for boats. The owners still wanted $1,200,000, which was too much for the government.

Portland General Electric argued that they owned the rights to all the water flowing over the falls. The government considered building new locks on the east side of the falls instead. However, the company said the government would still have to pay for water rights.

In 1907, the Oregon state government set aside $300,000 to help the federal government buy the locks.

Purchase Completed

In 1912, the War Department approved buying the locks from Portland Railway, Light & Power Company for $375,000. The deal didn't close until 1915 because of legal issues. One problem was proving who owned the land, as the town of Linn City had been washed away by a flood in 1862, along with its records.

Before the government took over, some mills used water directly from the upper lock level. This created strong currents that made it hard for boats to navigate. As part of the sale, the U.S. government agreed to build a wall in the canal. This wall would create a separate water source for the factories, so it wouldn't affect boat traffic.

In April 1915, this wall was the biggest planned project for the locks, costing between $125,000 and $150,000. The government also planned to repair the lock gates and make the entrances to the locks deeper.

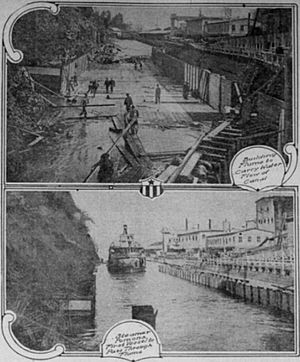

Reconstruction (1916–1917)

Major H.C. Jewett and E.B. Thomson oversaw the reconstruction of the canal and locks. Work on the new wall began in April 1916. By September 1916, about 1,000 feet of the wall, which separated the canal from the industrial water channel, had been built.

To keep river traffic moving during construction, the Army Corps of Engineers built a temporary wooden channel called a flume. This flume was 42 ft (13 m) wide and 6 ft (2 m) deep. Its inside was sealed with oil-treated canvas. This allowed the main canal to be drained for concrete work.

The wall was finished on September 1, 1917. It was 1,280 ft (390 m) long and over 50 ft (15 m) high in some places. It cost less than the estimated $150,000. Congress had also set aside $80,000 to improve the lower locks. However, shippers wanted this work delayed until 1918 so it wouldn't interfere with moving the 1917 harvest.

Recent Repairs and Closure

The locks closed in January 2008 because there was no money for inspections and repairs. In April 2009, as part of a government economic plan, $1.8 million was given to repair the locks. Another $900,000 was added in October 2009 for more repairs and operating costs. The locks reopened in January 2010, with the Willamette Queen being the first boat to pass through. They stayed open through the summer of 2010.

Due to a lack of federal money, the locks did not reopen in 2011. In December 2011, they closed again because the gate anchors were badly rusted. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers then said the locks were "non-operational." They were worried that using the locks could be dangerous. The locks are expected to stay closed permanently because there isn't enough boat traffic to make repairs a high priority. However, some groups are pushing for the Army Corps of Engineers to reopen the locks, at least for part of the year.

Historic Status

The Willamette Falls Locks were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. This means they are recognized as an important historical site.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |