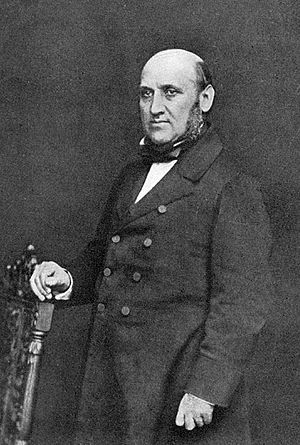

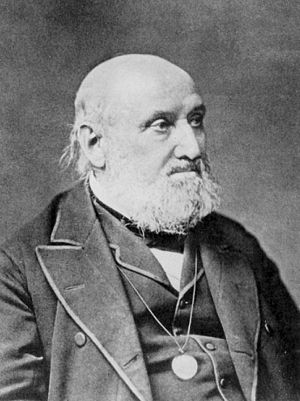

William Farr facts for kids

William Farr (born November 30, 1807 – died April 14, 1883) was a British doctor who studied how diseases spread. He is known as one of the people who helped create the field of medical statistics. This means he used numbers and data to understand health and illness.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

William Farr was born in Kenley, Shropshire, England. His family was not wealthy. A kind local person, Joseph Pryce, helped him when his family moved to Dorrington. In 1826, William worked as a "dresser" (a surgeon's assistant) at the Royal Salop Infirmary in Shrewsbury. He also learned about being an apothecary, which was like a pharmacist and doctor combined.

When Joseph Pryce passed away in 1828, he left William Farr some money. This allowed Farr to travel and study medicine in France and Switzerland. He returned to England in 1831 and continued his studies in London. By 1832, he was a qualified apothecary. He got married in 1833 and started his own medical practice in London. He soon became very interested in medical writing and using statistics in medicine.

Working at the General Register Office

In 1837, the General Register Office (GRO) was put in charge of collecting information for the United Kingdom Census 1841. Farr was hired there, first temporarily, to help with birth, death, and marriage records.

Later, with strong support from important people like Edwin Chadwick, Farr got a permanent job at the GRO. He became the first person to collect and analyze scientific health data, making him a key statistician. He worked closely with the first Registrar General, Thomas Henry Lister, to improve how census data was collected.

Farr's main job was to gather official medical statistics for England and Wales. His most important achievement was creating a system to regularly record why people died. This new system made it possible to compare, for example, how many people died in different jobs.

Joining Important Groups

In 1839, Farr joined the Royal Statistical Society, a group for people who work with statistics. He was very active there, serving as treasurer, vice-president, and even president over the years. In 1855, he was chosen to be a Fellow of the Royal Society, which is a big honor for scientists. He also helped start the Social Science Association in 1857.

Understanding Epidemics

In 1840, William Farr wrote a letter for the Annual Report of the Registrar General. In this letter, he used mathematics to study death records from a recent smallpox outbreak. He suggested that even if we don't know the exact cause of epidemics, we can still study how they behave. He believed we could find the "laws" of how diseases spread by observing them.

He showed that during the smallpox epidemic, the number of deaths each quarter looked like a bell-shaped curve when plotted on a graph. He noticed that other recent epidemics followed a similar pattern.

Researching Cholera

There was a huge outbreak of cholera in London in 1849, which killed about 15,000 people. London was the biggest city in the world then, and the River Thames was very dirty with sewage. At first, Farr believed that cholera was spread by bad air, a theory called the miasma theory. He also thought that how high up a place was (its elevation) was a major reason for cholera outbreaks.

During another cholera epidemic in 1853-54, Farr collected even more data. Around the same time, a doctor named John Snow used data from the GRO. Snow believed that people got cholera by swallowing something, and it then grew in their intestines. Snow also looked at death statistics for people who got water from two different companies in South London. He found that customers of the company that drew dirty water from the Thames were much more likely to get sick.

Farr was part of a committee that studied the epidemic in 1854. At that time, many people still thought cholera had many causes. Snow's idea that it was only caused by a germ was not fully accepted, but his evidence was taken seriously. Farr's own research was detailed and showed that fewer people died from cholera in higher areas.

By the time of another epidemic in 1866, John Snow had passed away. However, Farr had come to accept Snow's explanation for how cholera spread. Farr wrote a detailed report showing that deaths were very high for people who got their water from a specific reservoir in East London. After Farr's work, Snow's explanation was finally considered proven.

Later Life and Achievements

In 1858, Farr studied how health was connected to being married. He found that married people tended to be healthier than unmarried people, and widowed people were the least healthy.

Farr helped with the 1871 census. He retired from the General Register Office in 1879. That same year, he received special honors, including the Companionship of the Bath and the Gold Medal of the British Medical Association. These awards recognized his important work in biostatistics, which is the use of statistics in biology and medicine.

In his final years, new discoveries in bacteriology (the study of germs) changed how medical problems were understood. Statistics also became more mathematical. William Farr passed away at age 75 in London in 1883. He was buried at Bromley Common.

His Writings and Ideas

In 1837, Farr wrote a chapter called "Vital Statistics" for a book about the British Empire. He also started his own medical journal, but it only lasted a few months.

Farr used his job at the GRO to do more than just collect data. He used mathematical ideas from actuaries (people who calculate risks for insurance) to create national life tables. These tables showed how long people were expected to live at different ages.

Farr also had a theory about "zymotic diseases." He believed that diseases like epidemics and contagious illnesses were caused by dirt and crowded living conditions. He saw urbanization (more people living in cities) and population density as big public health problems.

A collection of his important statistical writings was published in 1885.

In TV Shows

William Farr was shown in an episode of the 2003 British TV show Seven Wonders of the Industrial World. The episode was called "The Sewer King."

His Family

William Farr's first wife, whom he married in 1833, passed away from tuberculosis in 1837. He married Mary Elizabeth Whittal in 1842, and they had eight children. In 1880, people raised money to help his daughters after he lost money in bad investments.

One of his daughters, Henrietta, married an artist named Henry Marriott Paget. Another daughter, Florence Farr, was also a painter and artist. She was a model for many famous art deco artworks.

How He Is Remembered

William Farr's name is on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of important public health pioneers were chosen to be on the school building when it was built in 1926.

In 1884, a type of fungi was named Farriolla in honor of William Farr.

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |