William Kitchen Parker facts for kids

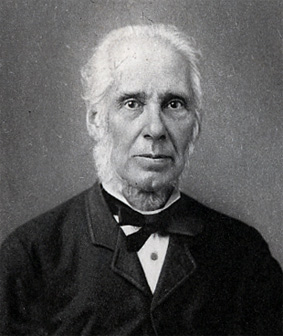

William Kitchen Parker (born June 23, 1823 – died July 3, 1890) was a British doctor, zoologist (someone who studies animals), and comparative anatomist (someone who compares the body structures of different animals). Even though he came from a simple background, he became a famous professor of anatomy and physiology at the College of Surgeons in England.

He was chosen as a member of the Royal Society in 1865 and received the Royal Medal in 1866 for his important work. From 1871 to 1873, he was the President of the Royal Microscopical Society, which studies tiny things using microscopes.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Parker was born in a small village called Dogsthorpe, near Peterborough. His father, Thomas Parker, was a farmer. William was the second son in his family, and sadly, six of his brothers and sisters died when they were very young.

William went to local village schools and also helped out on the family farm. He soon realized that farming wasn't what he wanted to do. He told his father, and then he went to Peterborough Grammar School for a short time.

In 1842, he started learning to be a surgeon. During this time, he spent his free hours teaching himself about plants. He became very knowledgeable about botany (the study of plants). He also collected and dissected (carefully cut open to study) birds and mammals. He made many beautiful and accurate drawings of what he saw.

Family Life

While he was still a student, Parker married Elizabeth Jeffery. They had seven children: three daughters and four sons. Many of his sons followed in his footsteps and became important scientists:

- His first son, Thomas Jeffery Parker, became a professor of zoology in New Zealand.

- His second son, William Newton Parker, became a professor of biology in Cardiff.

- His fourth son became a surgeon.

William Kitchen Parker became good friends with another famous scientist, Thomas Henry Huxley. He even named one of his sons after Huxley.

Later in his life, Parker received an annual grant from the Royal Society to help with his research. He was also given a special pension (regular payment) from the government because of his important scientific discoveries. He is buried in a cemetery in Wandsworth.

Medical Training and Shift to Zoology

Parker studied at King's College London from 1844 to 1846. He also attended Charing Cross Hospital. He was known for drawing sketches during lectures instead of taking notes, and he remembered everything very well. He created many detailed drawings and skeletons of birds and mammals.

For many years, Parker worked as a general doctor in London. This job helped him support his family. However, his true passion was zoology, which he learned all by himself. He is now remembered as a zoologist, even though he was trained as a doctor. Many famous naturalists of his time, like Thomas Henry Huxley and Richard Owen, also started their careers in medicine before focusing on natural history.

Discoveries in Zoology

Studying Tiny Creatures: Forams

Parker first used a microscope during his medical studies. Later, he started collecting sand and found tiny creatures called Foraminifera, or "forams" for short. These are microscopic, single-celled creatures that have tiny shells.

Parker became one of the top experts on forams. He worked with other scientists, like Thomas Rupert Jones, and together they wrote many scientific papers about these amazing tiny creatures.

Bird Anatomy

At the same time, Parker also worked on studying the skeletons and body parts of vertebrates (animals with backbones), especially birds. He made hundreds of preparations of bird wings and many complete bird skeletons. This work led to many scientific papers about birds, including one on the famous ancient bird, Archaeopteryx.

Understanding the Vertebrate Skull

One of Parker's most important contributions was his work on the vertebrate skull. His teacher, Richard Owen, had a popular idea that all vertebrate skulls were variations of a basic "archetype" or blueprint. Owen believed that the bones of the skull were just four modified vertebrae (bones of the spine).

However, Parker, along with Thomas Henry Huxley, challenged Owen's idea. They used embryology (the study of how animals develop from embryos) to show that Owen's theory was not correct. Parker carefully studied how the skulls of many different vertebrates developed from their earliest stages. He showed that the skull's development was much more complex and didn't fit Owen's simple "vertebrae" idea.

From 1865 to 1888, Parker published many detailed studies on the vertebrate skull. His work helped to completely change how scientists understood the skull and proved Owen's "archetype" theory wrong.

The Shoulder-Girdle

Parker also did important work on the pectoral girdle, which is the scientific name for the shoulder bones. He showed that the shoulder bones in fish are completely separate from the skull. This discovery also helped to prove that Owen's ideas about how limbs (arms and legs) developed were incorrect.

Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons

In 1873, Parker was asked to become a professor at the Royal College of Surgeons. He took a special exam and was appointed Professor. He shared this important position with another professor, William Henry Flower.

A Unique Writing Style

It seems Parker found writing difficult, and his scientific papers could sometimes be hard to understand. However, he was a great speaker and had a wonderful imagination. He often got help from friends to write his books.

Even though his scientific writing could be confusing, he had a fantastic way with words when describing things. For example, when talking about an extinct giant sloth called the Megatherium, he wrote:

"Let us, however, try to imagine a Megatherium waking up after lazily dozing a month or two during the dry season... setting to work to break his fast. As far as can be judged by the tools he had to work with—paws a yard, and claws a foot, in length—the first thing to be done was to throw a few hundredweights of earth from the roots of some large tree. Now he changes his tactics... he hugs the tree... and, busily digging still, not now with his fore, but with his hind, paws, his great weight resting upon his haunches and his tail, he, with many groans, sways the big tree to and fro; at last with a great crash it falls..."

This shows his amazing ability to paint a picture with words, which was very different from typical scientific writing of his time.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |