Foraminifera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Foraminifera |

|

|---|---|

|

|

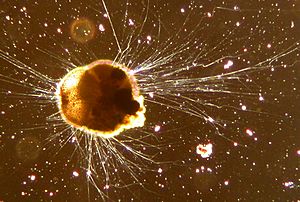

| Live Ammonia tepida (Rotaliida) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Clade: | SAR |

| Phylum: | Retaria |

| Subphylum: | Foraminifera d'Orbigny, 1826 |

| Subdivisions | |

|

"Monothalamea"

Tubothalamea

Globothalamea

incertae sedis

|

|

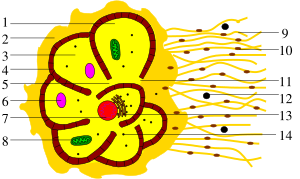

Foraminifera (pronounced fə-RAM-ə-NIH-fə-rə), often called "forams," are tiny, single-celled organisms. They are a type of protist with special, sticky, flowing parts called ectoplasm. They use these parts to catch food and move around. Most forams also have an outer shell, called a "test", which can come in many shapes and be made of different materials.

Many foraminifera live in the ocean, either on the seafloor sediment (these are called benthic) or floating in the water (these are called planktonic). Some can also be found in freshwater or even in soil. Their shells are usually made of calcium carbonate (like chalk) or tiny bits of sand glued together.

There are over 50,000 known types of forams, including both living and fossil species. Most are smaller than 1 millimeter, but some can grow much larger, even up to 20 centimeters!

Contents

Discovering Foraminifera

When were forams first noticed?

People have known about foraminifera for a very long time! The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote about them in the 5th century BCE. He noticed them in the rock used to build the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. Today, we know these were large fossil forams called Nummulites. Later, in the 1st century BCE, Strabo thought these fossils looked like lentils left by the pyramid builders.

How did scientists study forams?

The first time someone looked at a foram under a microscope was in 1665. Robert Hooke drew one in his book Micrographia. Later, in 1700, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek also drew foram shells, calling them "minute cockles."

In 1826, a scientist named Alcide d'Orbigny studied these tiny creatures. He noticed that their shells had small holes between the different sections. He named the group "foraminifères," which means "hole-bearers" in Latin. This is where the name Foraminifera comes from!

Later, in 1835, Félix Dujardin realized that forams were not tiny cephalopods (like squid or octopus), but actually a type of protozoan (a single-celled organism). Scientists like Henry Bowman Brady and Joseph Augustine Cushman continued to study and classify forams, helping us understand their different types. Modern scientists use advanced tools, like looking at their DNA, to learn even more about how different forams are related.

What are Foraminifera like inside?

The most noticeable part of most foraminifera is their hard shell, or test. These shells can have one or many sections, and they can be made of different materials like protein, sand, or calcite. Some forams don't have shells at all!

Unlike the shells of snails or corals, a foram's shell is actually *inside* its cell membrane. The cell's parts are inside the shell, and tiny holes in the shell allow the foram to extend its sticky, branching arms, called "granuloreticulose pseudopodia," outside.

How do forams use their arms?

These special arms look granular under a microscope. They can stretch out and pull back, and they can even split and rejoin. Forams use these arms for many things:

- Moving around

- Sticking to surfaces

- Getting rid of waste

- Building their shells

- Catching food, like tiny diatoms or bacteria

Some forams have large, empty spaces inside their cells called vacuoles. Scientists think these might store things like nitrate. Forams also have tiny powerhouses called mitochondria spread throughout their cells, which help them get energy.

Where do Foraminifera live?

What are foram habitats like?

Most modern foraminifera live in the ocean. They are found in many different places:

- On the seafloor: Many benthic forams live in soft sand or mud, moving between the layers. Others attach to rocks or seaweed.

- Floating in the water: Planktonic forams float at different depths in the ocean.

- Brackish or freshwater: Some forams can live in water that's a mix of fresh and salty, or even in completely fresh water.

- On land: A few rare types of forams have been found living in soil!

Foraminifera can even live in the deepest parts of the ocean, like the Mariana Trench. In these extreme depths, the water pressure is so high that calcium carbonate shells would dissolve. So, the forams found there have shells made of organic material instead.

What do forams eat?

Most forams eat smaller organisms and bits of dead organic matter. Some specialize in eating tiny plants called phytodetritus or diatoms. Some benthic forams build special "feeding cysts" by surrounding themselves with sediment and organic particles using their arms.

Some forams are even predators! They can hunt and eat small animals like copepods. Some even eat other forams, drilling holes into their shells to get to the soft insides. Other forams are filter feeders, catching tiny particles floating in the water.

Do forams have enemies?

Yes, many larger animals eat foraminifera. These include other tiny creatures, fish, shorebirds, and even other foraminifera. Sometimes, predators might be more interested in the calcium from the foram shells than the foram itself! Some types of aquatic snails are known to specifically hunt and eat forams.

Forams are very tough! Some benthic foraminifera can survive in water with very little or no oxygen for over 24 hours. This helps them live in places where oxygen levels can change a lot, like in the mud on the seafloor.

Foraminifera Life Cycle

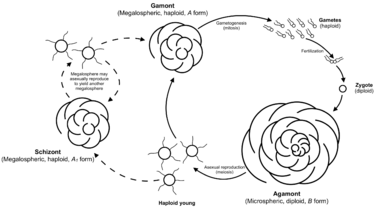

Foraminifera have an interesting life cycle that involves two main stages, which often look very similar. They switch between a stage with one set of chromosomes (called haploid) and a stage with two sets of chromosomes (called diploid).

How do forams reproduce?

1. Haploid Stage (Gamont or "A" form): This stage starts with a single nucleus. When it's ready to reproduce, it divides many times to make thousands of tiny gametes. These gametes are like tiny swimming cells, each with two little tails (flagella). They are released into the water. Any two gametes from the same species can join together.

2. Diploid Stage (Agamont or "B" form): When two gametes join, they form a new cell called an agamont. This cell has two sets of chromosomes and multiple nuclei. As the agamont grows, it reproduces asexually. Its cell contents leave the shell and divide through a process called meiosis to create many new haploid offspring. These offspring then start to form their own shells and grow into the haploid "A" form, starting the cycle again.

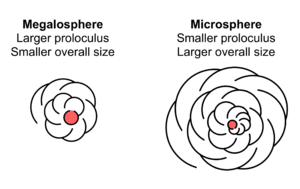

Scientists have noticed that the "A" form (gamont) usually has a larger first chamber in its shell, but the "B" form (agamont) often grows to be larger overall with more chambers.

Forams tend to grow larger and reproduce more slowly in colder, deeper water. The "A" forms are usually much more common than the "B" forms. This is probably because it's harder for two tiny gametes to find each other and join in the vast ocean.

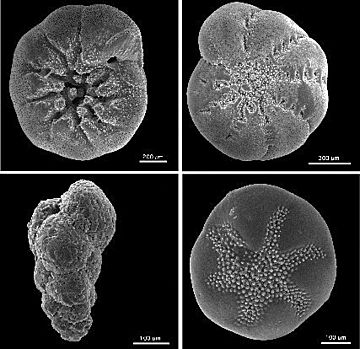

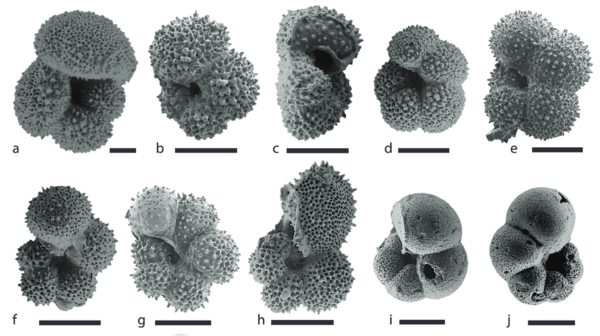

Foraminifera Shells

The shells of foraminifera, called "tests," protect the organism inside. Because these shells are often hard and last a long time, they are a huge source of information for scientists.

What do foram shells look like?

Foram shells have openings called apertures, which allow the cell's contents to extend outside. The main opening can be many different shapes, like round, crescent-shaped, or star-shaped. Some forams have teeth, flanges, or lips around their openings. A foram might have one main opening or many.

The overall shape of foram shells varies a lot. They can have just one chamber (unilocular) or many chambers (multilocular). As the foram grows, it adds new chambers to its shell. Some shells spiral, others are arranged in a line, and many other shapes exist.

How old are foram shells?

Fossil foram shells have been found that date back to the Ediacaran period, over 540 million years ago! Many marine sediments, like the limestone used to build the pyramids of Egypt, are mostly made of fossil foraminifera. It's estimated that forams living on reefs produce about 43 million tons of calcium carbonate every year!

Scientists have also discovered that some organisms, like the naked amoeba Reticulomyxa and the strange xenophyophores, are actually foraminifera that don't have shells.

Foraminifera and Earth's History

How do forams help us understand the past?

When planktonic foraminifera die, their shells sink to the seafloor and become part of the sediment. Scientists use special drilling techniques to collect these sediments, which contain countless fossil foram shells. This gives us an amazing record of life and Earth's climate going back to the mid-Jurassic period!

Because different types of foraminifera live in specific environments, their fossils can tell us a lot about ancient oceans. For example, they can reveal:

- How salty the water was

- How deep the ocean was

- How much oxygen was in the water

- How much light reached the seafloor

By studying the forams in different rock layers, scientists can track how climates and environments have changed over millions of years. For example, the ratio of planktonic (floating) to benthic (bottom-dwelling) forams can tell us how deep the water was when the rocks formed.

What do foram shells tell us about climate change?

The shells of fossil foraminifera are like tiny time capsules! They are made from elements found in the ancient seas where they lived. By studying the different types of stable isotopes (like oxygen and carbon) and trace elements (like magnesium or boron) in their shells, scientists can figure out:

- Past global temperatures and the amount of ice on Earth (from oxygen isotopes).

- The history of the carbon cycle and how productive the ocean was (from carbon isotopes).

- Information about global temperature cycles and how continents weathered (from trace elements).

Scientists also use patterns in planktonic foram fossils to reconstruct ancient ocean currents. For example, the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM), a period of rapid global warming about 56 million years ago, is studied using foraminifera. It helps scientists understand how massive amounts of carbon can affect the ocean and atmosphere, similar to today's global warming.

How do forams help with dating rocks?

Foraminifera are very useful in biostratigraphy, which is the science of dating rock layers. Because they are small, have hard shells, and complex shapes, individual foram species are easy to recognize. Each species lived for a specific period of time in Earth's history.

By looking at the types of forams found in a rock layer, scientists can compare them to a known timeline of foram appearances and disappearances. This helps them figure out the age of the rocks, especially when other dating methods, like radiometric dating, can't be used. This amazing use of foraminifera was discovered in 1920 by Alva C. Ellisor.

Modern Uses of Foraminifera

Foraminifera are not just important for understanding the past; they have many uses today!

How do forams help the oil industry?

The oil industry uses tiny fossils like forams to find places where oil and gas might be. Forams help them figure out the age of rock layers and what the ancient environment was like in oil wells. Some fossil forams can even tell scientists how hot the rocks got deep underground, which is important for knowing if oil has formed.

How do forams help with the environment?

Living foraminifera are used as bioindicators in coastal areas. This means they can show us how healthy an environment is. For example, they can indicate the health of coral reefs. Because their calcium carbonate shells can dissolve in acidic conditions, foraminifera are especially sensitive to changes in climate and ocean acidification. Studying them helps us understand how these changes affect marine life.

What about archaeology?

Foraminifera can even help in archaeology! Some types of stone, like limestone, contain fossilized foraminifera. By looking at the types and amounts of these fossils in a stone sample, archaeologists can match it to a specific source where that stone naturally occurs. This helps them figure out where ancient people got their building materials or tools.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Foraminifera para niños

In Spanish: Foraminifera para niños