William Montague Cobb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

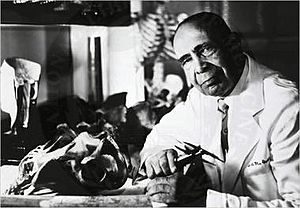

William Montague Cobb

M.D. Ph.D.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 12, 1904 |

| Died | November 20, 1990 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Case Western Reserve University |

| Spouse(s) | Hilda B. Smith |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Ruth Smith Lloyd (sister-in-law) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Howard University |

| Doctoral advisor | Thomas Wingate Todd |

William Montague Cobb (1904–1990) was an American doctor and a physical anthropologist. He was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology. His main work was studying the idea of race and how it negatively affected people of color.

Cobb was also the first African American President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He spent his career as a doctor and professor at Howard University. He worked hard to help African American researchers and was very active in civil rights. Cobb wrote many articles and taught over 5,000 students.

Contents

Who was William Montague Cobb?

William Montague Cobb was born on October 12, 1904, in Washington, DC. His mother, Alexizne Montague Cobb, had some Native American heritage. His father, William Elmer Cobb, was from Selma, Alabama. They met in Washington, DC, where his father ran a printing business for the African American community.

Cobb became interested in anthropology because of a book his grandfather owned. This book had pictures of humans from different races, drawn with what Cobb called "equal dignity." This made him think about the idea of race. He noticed that in society, people were not treated with "equal dignity."

Cobb went to Dunbar High School in Washington, DC, starting in 1917. He was a great student and athlete. He won championships in cross-country and boxing. He married Hilda B. Smith, and they had two children. Cobb passed away from pneumonia on November 20, 1990, at 86 years old.

How did Cobb get his education?

After finishing Dunbar High School in 1921, Cobb earned his first degree from Amherst College in 1925. He then received a scholarship to study embryology (the study of how living things develop before birth) at the Woods Hole Marine Biology Laboratory.

He earned his medical degree (MD) in 1929 from the Howard University Medical School. While in medical school, he worked different jobs. After graduating, he accepted a job offer from Howard University.

The Dean of Howard University, Numa P. G. Adams, wanted to create a new team of African American doctors. Cobb wanted to build a lab at Howard University for African American scholars. This lab would help them study racial biology and challenge wrong ideas about race. Cobb was sent to study under anthropologist Thomas Wingate Todd at Case Western Reserve University.

For his Ph.D., Cobb studied a large collection of human skeletons called the Hamann-Todd Skeletal Collection. He earned his Ph.D. in Anthropology in 1932. His research was published as Human Archives the next year.

What did Cobb do in his career?

After getting his Ph.D., Cobb stayed at Case Western Reserve University for a while. He continued studying the Hamann-Todd Collection, focusing on how skull bones join together. His 1940 paper, "Cranio-Facial Union in Man," showed his skill as an anatomist (someone who studies the body's structure).

Cobb returned to the Howard University Medical School in 1930. He taught there for most of his career. He also created the W. Montague Cobb Skeletal Collection at the university. In 1969, he became the university's first distinguished professor. He retired in 1973. Cobb also taught at many other universities across the country.

Cobb was very involved in many groups related to anthropology and medicine. He was an active member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. He served as its vice president and later as president. He also held leadership roles in other important scientific and medical societies.

Throughout his life, Cobb worked to create more opportunities for African Americans. This included helping them in society and in health sciences. He was a strong member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He served as its president from 1976 to 1982.

In 1957, Cobb started the Imhotep Conferences on Hospital Integration as part of the NAACP. These yearly meetings aimed to end segregation in hospitals and medical schools. He was also active in the National Medical Association, which helps African American doctors. He edited their journal, the Journal of the National Medical Association, from 1944 until his death. He also served as the association's president. Cobb wrote articles about race and health for popular African American magazines like Negro Digest and Ebony.

What was Cobb's scholarship about?

Cobb used his knowledge of anatomy and medicine to study many topics. These included African American health, child development, and proving wrong the scientific reasons used to support racism. His work was a form of "applied anthropology," meaning he used his studies to solve real-world problems.

He strongly disagreed with ideas that ranked human groups based on race. He often used examples to show the strength of African Americans. For instance, he argued that the Transatlantic slave trade acted like a filter. He believed it led to a genetically stronger African American population compared to European Americans.

Cobb often used his knowledge of biology to fight racist ideas about differences between African Americans and European Americans. One famous study was his 1936 paper, "Race and Runners." In this work, Cobb looked at the case of Jesse Owens. Owens won four gold medals in the Olympics. Some people claimed his success was due to "African American genes." They thought Black people were stronger but less intelligent.

Cobb studied Owens and other top African American athletes. He showed that their success was not due to a shared "racial trait." He explained that the body features needed for a great athlete in one sport would be different from another. Cobb concluded that African American athletes succeeded because of "training and incentive," not any special physical gift.

Later in his career, Cobb thought more deeply about humanity. He used ideas from biology to explain problems in society. His important 1975 paper, "An anatomist's view of human relations," discussed a conflict in human nature. He called it the struggle between Homo sapiens ("Man the Wise") and Homo sanguinus ("Man the Bloody").

Cobb said that civilization and ethics are like new body traits, similar to how humans learned to walk on two legs. He argued that "Man the Wise" is fighting against the older, violent side of humans, "Man the Bloody." He believed this history of violence is hard to overcome. In 1988, Cobb's last paper, "Human Variation: Informing the Public," applied these ideas to the fast changes of the late 20th century. He saw this time as a chance to fight racism but also a risk for inequality to become more fixed in society.

What is Cobb's legacy?

Cobb is remembered for bringing social responsibility to anthropology. He was an "activist scholar" who used his studies to fight racism and inequality. He did research in anatomy to disprove racist ideas about social differences. He believed that scholars must be responsible for their thoughts and actions, and for society. He felt that scientific work shapes culture and society.

Cobb was one of the first anthropologists to study how segregation and racism affected the African American population. He wanted to create resources so that others could continue this work. One of his biggest contributions is the large skeletal collection he built at Howard University. It is now part of the W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory. This lab also holds the New York African Burial Ground collection.

Cobb was deeply involved in the fight for freedom and equality for African Americans. He held many roles in African American organizations, like the National Urban League. He was also a longtime editor of the Journal of the National Medical Association, the first African American medical journal. He served on the board of the NAACP from 1949 until his death.

Cobb helped expand access to medical care. His activism led him to speak to Congress before Medicare and Medicaid were passed in 1965. He was invited by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the signing of this important bill.

During his life, over 100 organizations honored Cobb for his work. He received the Henry Gray Award, the highest award from the American Association for Anatomy. He also received the U.S. Navy's Distinguished Public Service Award. Several universities gave him honorary doctorates. In 2020, the American Association for Anatomy named the W.M. Cobb Award in Morphological Sciences after him.

Selected publications

- "Human Archives" – 1932.

- "Race and Runners" –1936.

- "Cranio Facial Union of Man" – 1940.

- "An anatomist's view of human relations. Homo sanguinis versus Homo sapiens--mankind's present dilemma" – 1975.

- "Human Variation: Informing the Public" – 1988.

Cobb wrote over 1100 publications in total.

See also

- Manet Helen Fowler

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |