Windsor soup facts for kids

| Type | Soup |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Great Britain |

| Main ingredients | calf's feet, bouquet garni, Madeira wine |

| Variations | White and brown soups |

Windsor soup is a traditional British soup. It was very popular during the Victorian (when Queen Victoria ruled) and Edwardian (when King Edward VII ruled) times. Later, people started calling it Brown Windsor soup, especially after the 1920s. This name often meant it was a cheaper, less fancy soup with unknown ingredients.

Even though it started as a fancy dish made by famous chefs, the "Brown Windsor" version became known as a simple, often not-so-tasty, meal served in places like schools or hospitals. It even became a joke about bad British food in the mid-1900s!

Contents

How Windsor Soup Began

The first known recipe for a soup like this appeared in 1834. Henderson William Brand, who was a chef for King George IV, published a recipe called Vermicelli Soup, a la Windsor. He said this white broth and noodle soup was a favorite of King George III and King George IV.

Eleven years later, in 1845, another important recipe came out. It was in a cookbook called The Modern Cook by Charles Elmé Francatelli. He was Queen Victoria's head chef. His recipe was called Calf's Feet Soup, a la Windsor. This soup was made from calf's feet or oxtail broth. This made it thick and jelly-like. It also had white wine, cream, chicken, and noodles. This was a white soup.

Francatelli's cookbook was very popular. Many Victorian women used it to cook like the Queen. This helped Windsor soup become well-known in homes and fancy restaurants. Even though people thought Queen Victoria ate it often, it was rarely on her royal menus. And it was never a "brown" soup for her!

Different Kinds of Windsor Soup

Throughout the 1800s, many chefs made their own versions of Francatelli's recipe. Most recipes used calf's feet and Madeira wine. Sometimes, chefs added caramel coloring to make it a deep brown. They might also add cayenne pepper for a spicy kick.

There was even a 'white' version made with Windsor beans in 1855. Other recipes used mutton, beef, and rice. A famous French chef named Auguste Escoffier made a creamy Windsor soup at the Savoy Hotel in the 1890s. This hotel was a favorite spot for English royalty, including the Prince of Wales.

When Windsor Soup Lost Its Shine

By the 1920s, people weren't as excited about Windsor soup anymore. It started to become a symbol of boring British food. Many people said that by the 1930s, soup-making wasn't very good, and hotels often served "disgusting brown soups," which were called "Brown Windsor soup."

The "brown Windsor soup" first appeared in the 1920s. It was served to many people in cafes and cafeterias. For example, a cafe in Portsmouth advertised "Soup – Tomato or Brown Windsor" in 1926. Other places like Bobby's in Bristol and Isaac Benzie in Scotland also offered "Potage Brown Windsor" on their menus in the early 1930s.

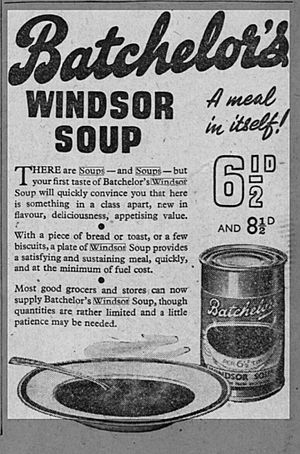

It became easier to buy soup in cans and packets. For example, "Batchelor's Windsor Soup" was sold in a tin can during the 1940s. During wartime rationing, some towns even kept cans of Windsor soup in stock. People remembered it tasting like "gravy browning." After the war, rationing continued into the 1950s. Leftovers were often blended into brown "mystery soups." These soups might have had nothing to do with the original Windsor recipe. They were often thin, tasteless, and made from simple broth powder and thickener.

The Jokes Begin

In the 1950s, people started making fun of Brown Windsor soup. It was seen as something served in cheap, rundown places, even though it had a fancy-sounding name. One writer noted that it was a "real soup," but it was "largely associated with shabby boarding houses trying to sound posh."

A famous entertainer, Nicholas Parsons, said it was a big part of his childhood. He remembered that "Nearly every cheap hotel had brown Windsor soup." He said hotels would use all their leftover meat to make it. It was so common that people either laughed at it or ignored it. It became a joke. By the 1980s, it was becoming a legend, with people saying, "Brown Windsor soup, thanks heavens, is an endangered species."

Myths and Stories About the Soup

Many stories and ideas grew around Windsor soup. Some people believe that Brown Windsor soup wasn't actually popular. They think it was mostly a joke that started with a 1953 movie called The Captain's Paradise. According to this idea, authors later wrote about the soup in their memories, perhaps exaggerating its popularity or even its existence for humor.

Some researchers found recipes for "brown soup" that were made from bones and were similar to Windsor soup. They thought that maybe "Windsor soup" and "brown soup" got mixed up in people's memories over time.

People also noticed that "Brown Windsor soup" sounded a lot like "Brown Windsor soap", which was well-known in Victorian times. They wondered if there was a connection.

Some authors incorrectly stated that the first mention of Brown Windsor soup was in 1943. Also, one author in 1915 thought the soup came from France, probably because of its early French name in The Modern Cook.

Brown Windsor soup has often been linked to British trains. However, historians have had trouble finding proof that it was ever served on British Railways dining cars. Researchers at the National Railway Museum looked through many old menus but couldn't find any mention of it. Still, some authors, like Paul Spicer, said Brown Windsor was popular on British railways and "was often said to have built the British Empire." One author, Jane Garmey, wrote in 1981 that Brown Windsor was "continually served by British Railways in their dining cars." She remembered thinking it was the only soup served on a train because it was everywhere.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |