Witches' Sabbath facts for kids

A Witches' Sabbath was a supposed meeting of people believed to practice witchcraft and other magical rituals. The idea of a "Witches' Sabbath" became very popular in the 20th century, even though the term itself wasn't widely used in earlier times.

Contents

How the Term "Witches' Sabbath" Became Popular

Before the late 1800s, it was rare to find the English word "sabbath" used to describe a gathering of witches. The phrase became more common after historians like Henry Charles Lea (in 1888) and Joseph Hansen (in 1900) started using it. Hansen, a German historian, often used the German term hexensabbat when talking about old trial records.

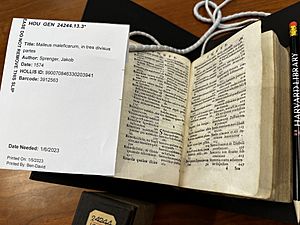

It's interesting that Malleus Maleficarum (1486), a very famous book about witches, doesn't actually use the word "sabbath" (sabbatum). Lea and Hansen's work likely helped make the term much more common, including in English.

Even earlier German folklore collections, like those by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s, don't mention hexensabbat in relation to magic.

French Writers and the Term

French writers, including those writing in Latin, used similar terms more often than German or English writers, though it was still quite rare. This might have links to how the Waldensians (a religious group) were treated by the Inquisition.

For example, in 1124, the term inzabbatos was used to describe Waldensians in Spain. Later, in the 1400s, terms like synagogam and "synagogue of Sathan" were used for Waldensians in France. These terms might refer to a Bible verse (Revelation 2:9). In 1458, a French author named Nicolas Jacquier used synagogam fasciniorum for what he thought was a witches' gathering.

About 150 years later, when witch hunts were at their peak, French writers still seemed to be the main ones using these related terms. However, they used them only sometimes. Lambert Daneau used sabbatha once (1581). Nicholas Remi also used the term sometimes (1588). Jean Bodin used the term three times (1580). Even the Englishman Reginald Scot (1585), who wrote against witch hunts, used the term only once, when quoting Bodin.

In 1611, Jacques Fontaine used sabat five times in a way that sounds like our modern understanding. The next year (1612), Pierre de Lancre seemed to use the term more often than anyone before him.

In 1668, a German writer named Johannes Praetorius published a book about the "Blockes-Berge" (a mountain). Its subtitle mentioned "witches' journey and magic sabbaths," showing the term was becoming more known in Germany.

Later, another French writer, Lamothe-Langon, used the term in his translations of Inquisition documents. Joseph Hansen later cited Lamothe-Langon as one of his sources.

Why Translators Started Using the Term More Often

Even though the word "sabbath" was not used much in historical records to describe witch gatherings, it became very popular in the 20th century.

Cautio Criminalis

In a 2003 translation of Friedrich Spee's book Cautio Criminalis (1631), the word "sabbaths" appears many times in the index. However, Spee himself, who wrote in Latin, never used words like sabbatha or synagoga. He most often used conventibus to mean a gathering of witches. This is where English words like "convention" and "coven" come from. Spee wrote Cautio Criminalis to argue against witch trials, as he had seen many people tortured.

Malleus Maleficarum

In a 2009 translation of Malleus Maleficarum (1486) by Heinrich Kramer, the word "sabbath" does not appear at all. The book describes a gathering using the word concionem, which is correctly translated as "assembly." The translator even added a note apologizing for the lack of the term "sabbath" in the original text.

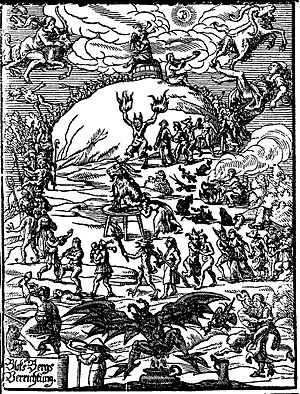

Witches' Sabbath in Art

The phrase "Witches' Sabbath" is also popular in recent translations of art titles, including:

- The Witches' Sabbath by Hans Baldung (1510)

- Witches' Sabbath by Frans Francken (1606)

- Witches' Sabbath in Roman Ruins by Jacob van Swanenburgh (1608)

- Witches' Sabbath (1798) and Witches' Sabbath or The Great He-Goat (1823), both by Francisco Goya

- Muse of the Night (Witches' Sabbath) by Luis Ricardo Falero (1880)

Were Witches' Sabbaths Real?

Modern researchers have found no proof that actual physical gatherings of witches ever happened. During the late Middle Ages and early modern Europe, many people truly believed in the power of witchcraft. This led to a great fear among some religious leaders that witches were secretly plotting to overthrow Christianity.

Women, especially older women, were often blamed for problems like famine, disease, and war. They became easy targets for this fear.

What People Believed Happened at a Sabbat

Ronald Hutton, a historian, says that the idea of the witches' sabbath was mostly made up from three older mythical ideas:

- A group of female spirits, sometimes with humans, led by a supernatural woman.

- A lonely, demonic hunter.

- A noisy group of dead people, often those who died too soon or violently.

The first idea, about female spirits, might have come from pre-Christian beliefs.

The book Compendium Maleficarum (1608) described a typical "witches' gathering" from the viewpoint of those who feared witches. It said witches would ride flying goats, step on crosses, be "re-baptized" by the Devil, kiss his behind, and dance in a circle.

These stories about the sabbat helped spread the belief in witchcraft. This also encouraged the hunting, prosecution, and execution of people accused of being witches.

Most descriptions of Sabbats came from priests, lawyers, and judges who never attended such gatherings. Or, they were written down during witchcraft trials. Many of these "testimonies" were given when the accused person was being tortured. This means they might have agreed to anything their questioners suggested.

Historian Norman Cohn argued that these stories mostly reflected the fears and imaginations of the time. They were influenced by a lack of knowledge, fear, and religious intolerance towards minority groups.

More recently, scholars like Emma Wilby suggest that while the scary parts of the sabbath story were made up by the people doing the questioning, the accused people themselves might have added to these ideas. They might have used popular beliefs about strange rituals or magical spells to describe the sabbath during their interrogations.

Possible Links to Real Groups

Some historians, like Carlo Ginzburg, believe that these testimonies might offer clues about what the accused people actually believed. Ginzburg found records of a group in northern Italy called benandanti. These people believed they could leave their bodies in spirit form. They thought they fought evil spirits in the clouds to bring good fortune to their villages. Or, they gathered at big feasts led by a goddess who taught them magic.

Ginzburg linked these beliefs to similar stories from other parts of Europe. In many of these stories, the meetings were described as happening "out-of-body" rather than physically.

See also

In Spanish: Aquelarre para niños

In Spanish: Aquelarre para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |