Zenú facts for kids

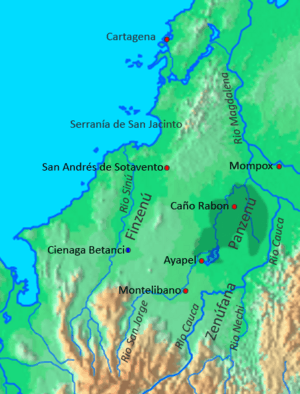

The Zenú or Sinú people were an amazing ancient culture in Colombia. Their homeland was in the valleys of the Sinú River and San Jorge River, and along the Caribbean coast near the Gulf of Morrosquillo. Today, these areas are part of the Córdoba Department and Sucre Department.

The Zenú culture thrived from about 200 BCE (Before Common Era) to around 1600 CE (Common Era). They built huge water systems and created beautiful gold art. Sadly, the gold buried with their dead attracted Spanish explorers, who took much of it. When the Spanish arrived, many Zenú people died from new diseases, hard labor, and high taxes. Their language disappeared about 200 years ago. However, in 2018, the Colombian Census counted 307,091 Zenú people still living in Colombia!

In 1773, the King of Spain set aside a large area of 83,000 hectares in San Andrés de Sotavento as a special reserve for the Zenú. This reserve was closed in 1905 by the National Assembly of Colombia. But the Zenú people fought to get their land back. In 1990, San Andrés de Sotavento was restored as a Zenú reserve, starting with 10,000 hectares and later growing to 23,000 hectares.

Contents

The Ancient Zenú: Before the Europeans Arrived

Around 200 BCE, groups of farmers and skilled goldsmiths lived in the valleys of the Sinú River, San Jorge River, Cauca River, and lower Nechí River. They all shared similar art, beliefs about life and death, and ways of living with nature. They got their food by hunting, farming, fishing, and trading raw materials and finished goods. Around 950 CE, about 160 people lived in every square kilometer of the San Jorge basin. After 1100 CE, for reasons we don't fully understand, the Zenú population decreased. They moved to higher lands that didn't flood, so they didn't need their drainage systems as much. They lived there until the Spanish arrived.

Amazing Water Systems

The area where the San Jorge River, Cauca River, Magdalena River, and Nechí River meet often flooded during the rainy season (April to November). This caused big problems for the people living there. So, starting around 200 BCE, the Zenú began building a clever system of channels. These channels helped them control the floods and made large areas suitable for living and farming. They kept expanding this system for a long time. Between 200 BCE and 1000 CE, it covered 500,000 hectares, mostly in the San Jorge basin. They also built channels in the lower parts of the Cauca and Sinú rivers.

The Zenú dug channels, some as long as four kilometers, connecting them to natural waterways. Smaller irrigation ditches were dug at right angles to these main channels. The soil they dug out was used to build long, artificial terraces, two to four meters high, where they built their homes. When the water levels were high, the channels directed water to their crop fields. When the water went down, the mud left behind was full of nutrients, making the land rich for farming. This amazing water management system was used for 1300 years!

After the Spanish arrived, the drainage system likely stopped working. The Spanish writers didn't mention it. Even though the system is now covered by marshes, you can still see the patterns of the channels in the landscape today.

Women: Important Leaders and Symbols

In Zenú culture, women were seen as symbols of fertility, wisdom, and respect. They often made clay figures of women and placed them in graves. These figures represented human and farming fertility. Having these statues in a grave symbolized new life and rebirth, just like seeds sprout and grow. During funerals, the whole community would gather with music and dance. They would build a mound over the grave and plant a tree on top. Golden bells were hung in the tree branches. Important women and chiefs wore round golden breastplates during ceremonies. These symbolized the pregnancy of women and the strength of men. The round shape of the mound and the breastplate reminded them of where new life begins. Because of this, women held great social and political power. When the Spanish found the Zenú culture in the 1500s, the main religious center of Finzenú, by the Sinú River, was led by a female chief named Toto. She governed several nearby villages.

Shiny Gold Art

The Zenú's network of water channels was also reflected in their art, culture, and beliefs. For them, the world seemed like a giant woven basket, where all living things were placed. This idea showed up in the patterns of their fishing nets, textiles, pottery, and gold items. Just as the channels were where daily life happened, people and animals appeared in the metal patterns of their cast semi-filigree earrings.

Semi-filigree was a special way the Zenú decorated their gold. It wasn't made by weaving gold threads, but by casting metal using the lost wax method. Besides casting, they also hammered gold into flat plates and raised designs. Their gold ornaments were usually made of a mix of metals with a lot of gold. They often showed animals like waterfowl, alligators, fish, cats, and deer. These animals were important for food and were also part of their culture. The animal world was shown in gold pendants and in gold ornaments that went on top of staffs.

Weaving and Basket Making

Most of the ancient Zenú textiles (woven fabrics) and wickerwork (baskets and woven items) have been lost over time. However, the tools they used to make these items, like needles and spindles made from bone, shells, and clay, have survived. We can learn about their woven fabrics from the many pictures of them on gold and ceramic objects. Women were often shown wearing long woven skirts with many different patterns.

What Made the Zenú Unique?

The designs found in Zenú gold and pottery show that the different ancient communities in these areas were connected by their politics and religion. The patterns on their textiles and clay baskets, the female clay figures, and the way they built burial mounds were similar for all the people living in these river valleys. Like their channel system, which was used for many centuries, these cultural features lasted a long time and are part of what we call the Zenú tradition. However, artists from different places in the area expressed these ideas in their own ways, so we can tell them apart. Still, they all showed a common Zenú identity.

The Zenú After the Europeans Arrived

From 1100 CE onwards, the Zenú population decreased for unknown reasons. Until the Spanish arrived, the Zenú lived on higher lands around Ayapel, Montelibano, and Betanci. The Spanish explorers found this area by traveling along the Sinú River while looking for riches.

Under the Zenú, each river valley had its own province. The Sinú valley was called Finzenú, and its main city was Zenú. When the Spanish arrived, Finzenú was led by a woman named Toto. Their most important holy place and the cemetery where important leaders were buried was at Zenú, near the Betanci marsh. The San Jorge basin, where much of their food was grown, was called Panzenú. It was led by Yapel, and its main political center was Ayapel. Zenúfana, located between the Cauca and Nechí rivers, was the main place where gold was produced.

The Zenú believed that a mythical figure named Chief Zenúfana had once governed the lower Cauca and Nechí area. When the Spanish arrived, he was seen as the most important of the ancient chiefs. He had organized the entire territory of Great Zenú and given political, economic, and religious duties to the chiefs of Finzenú and Panzenú, who were his relatives. He had created laws and rules that were still followed when Pedro de Heredia invaded the country. The three chiefs had different but connected duties in politics, religion, and the economy.

Zenú in the Mountains

Around the time of the Spanish arrival, related groups of Zenú goldsmiths, traders, and sailors lived in the mountains of San Jacinto, Bolívar and along the banks of the Magdalena River. However, they were different from the lowland Zenú people. While the lowland Zenú used cemeteries and burial mounds, the mountain Zenú buried their dead in large pots placed under the floors of their homes.

Unlike the goldsmiths in the river valleys, these mountain goldsmiths used gold mixed with a lot of copper. These items were often made for many people to use. To make the surface of these objects look golden, they used a chemical heating process. This process dissolved the copper on the surface, leaving the gold behind. Over time, this golden layer often wears away, showing the oxidized copper underneath.

These items are similar to those from the lowland culture: fine cast circular and semi-circular filigree earrings, nose rings with horizontal parts, pendants with richly dressed people, circular or n-shaped nose rings, staff heads, bells, and figures that are part human and part amphibian with special headdresses. Some designs look very real, while others are more stylized. People are shown naturally: holding gourds, playing flutes and maracas, sitting on chairs with high backs, or standing.

Animals from the rugged mountains are often shown on these items, but animals from the marsh and river areas are also depicted. A special feature of the objects made in the San Jacinto mountains is that they show scenes, like ducks sitting on a branch, a cat-like figure fighting an alligator, or a man holding the claws of a bird of prey. Birds, cat-like figures, and amphibian figures are animals that are often linked with humans in their art.

Men and animals generally keep their own features, like beautifully dressed leaders with very stylized bodies. But they also found images that mix human and animal forms. These show a human face and a headdress like a bird's crest, with the body of an animal from a swampy area, such as a fish, a lizard, or a crustacean.

Some features of their goldwork were unique to these mountain people, but their work is closely related to that of the Zenú from the rivers. Since many items come from the San Jacinto mountains, it might have been an important place for making gold art. We don't know when gold production started in this area. However, because the themes and techniques are similar to the goldwork found in river valleys that was already being made by 200 BCE, it could have started a long time ago. Carbon dating has shown that gold production in San Jacinto definitely continued even after the Spanish arrived.

|

See also

In Spanish: Zenú para niños

In Spanish: Zenú para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |