Ľudovít Štúr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ľudovít Štúr

|

|

|---|---|

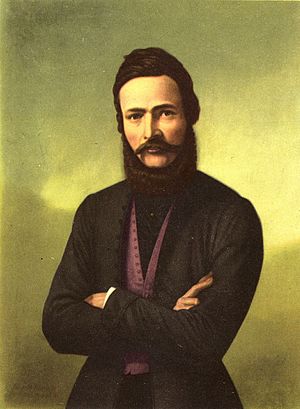

Portrait by Jozef Božetech Klemens

|

|

| Born | 28 October 1815 Zayugróc, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (now Uhrovec, Slovakia) |

| Died | 12 January 1856 (aged 40) Modor, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (now Modra, Slovakia) |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

Ľudovít Štúr (born October 28, 1815 – died January 12, 1856) was a very important Slovak leader, politician, and writer. He led the Slovak national revival in the 1800s. He also created the official Slovak language that people use today. Because of this, he is seen as one of the most important people in Slovak history.

Štúr helped organize Slovak volunteers during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. He was also a politician, poet, journalist, publisher, teacher, philosopher, and linguist. He was even a member of the Hungarian Parliament.

Contents

A Look at His Life

His Early Years

Ľudovít Štúr was born on October 28, 1815, in Uhrovec, which was then part of the Austrian Empire. He was the second child of Samuel and Anna Štúr. His father, Samuel, was a teacher and taught him basic subjects, including Latin.

From 1827 to 1829, Ľudovít studied in Győr at a lower grammar school. There, he learned more about history and improved his German, Greek, and Hungarian languages. These studies made him admire famous scholars like Pavel Jozef Šafárik.

In 1829, he moved to a new school. From 1829 to 1836, Ľudovít Štúr studied at the important Lutheran Lýceum in Pressburg (now Bratislava). He joined the Czech-Slav Society, which made him very interested in all Slavic nations. This school had a famous professor, Juraj Palkovič, who taught about the Czechoslovak language and old literature.

In 1831, Ľudovít Štúr wrote his first poems. For a short time in 1834, he stopped his studies because he didn't have enough money. He worked as a scribe for Count Károly Zay. Later that year, he went back to school. He was very active in the Czech-Slav Society, helping with letters and teaching younger students. In December 1834, he was chosen as the secretary of the Society.

Leading the Slovak Movement

In May 1835, Ľudovít Štúr convinced his friend Jozef Hurban to join the Slovak national movement. This movement aimed to make Slovaks proud of their language and culture. That same year, Štúr helped edit Plody ("Fruits"), a book of the best writings from the Czech-Slav Society members. He became the vice-president of the Society, teaching older students about Slavic history and literature.

In 1836, Štúr wrote a letter to a Czech historian, František Palacký. He explained that the Czech language used by Protestants in Slovakia was hard for ordinary Slovaks to understand. He suggested creating a single "Czechoslovak language." However, the Czechs didn't agree. So, Štúr and his friends decided to create a completely new Slovak language standard instead.

On April 24, 1836, Štúr led members of the Slovak national movement on a trip to Devín Castle. This old castle was a symbol of Slovak history. At the castle, they promised to work for their nation. They also took on extra Slavic names to show their dedication.

From 1836 to 1838, Štúr worked as an assistant to Professor Palkovič at the Lýceum. He taught about Slavic literature. Under his leadership, more and more students joined the Czech-Slav Society. In 1836, his poem Óda na Hronku ("An ode to Hronka") was published. In April 1837, the Czech-Slav Society was banned. But Štúr quickly started the Institute of the Czechoslovak Language and Literature, where the Society's activities continued. He also wrote articles for many newspapers and journals.

Studying in Germany and Early Political Ideas

From 1838 to 1840, Štúr studied at the University of Halle in Germany. He focused on languages, history, and philosophy. He was inspired by German thinkers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. During this time, his poems Dumky večerní ("Evening Thoughts") were published.

In 1839, Štúr traveled to Lusatia in Germany, where other Slavic people lived. He wrote a travel story about his trip called Cesta do Lužic vykonaná na jar 1839 ("A journey to Lusatia made in the spring of 1839").

In 1840, he returned to Bratislava. He continued working as Professor Palkovič's assistant at the Lýceum, teaching grammar and Slavic history. He also kept up his work at the Institute of the Czechoslovak Language.

Between 1841 and 1844, Štúr helped edit a literary magazine called Tatranka. He also started working to publish a Slovak political newspaper. He wrote texts defending Slovak rights. On August 16, 1841, Štúr and his friends climbed Kriváň, a mountain important to Slovak culture. This event is still celebrated today. In 1842, he tried to get permission to publish a newspaper, but it was denied.

Creating the Slovak Language

On February 2, 1843, in Pressburg, Štúr and his friends made a big decision. They decided to create a new, official Slovak language. This language would be based on the dialects spoken in central Slovakia. The goal was to unite all Slovaks, no matter which dialect they spoke.

In July 1843, Štúr's defense of the Slavs in Hungary, called Die Beschwerden und Klagen der Slaven in Ungarn über die gesetzwidrigen Übergriffe der Magyaren, was published in Germany. From July 11 to 16, 1843, Štúr, J. M. Hurban, and M.M. Hodža met in Hlboké. They agreed on how to make the new Slovak language official and how to introduce it to everyone. The next day, they visited Ján Hollý, an important writer who used an older Slovak language standard, to tell him about their plans.

On October 11, 1843, Štúr was told to stop teaching and was removed from his assistant position. However, he kept giving lectures. On December 31, 1843, he was officially removed from his job. In protest, 22 students left Pressburg in March 1844. Many of them went to study in Levoča. One of these students, Janko Matuška, wrote a hymn called "Nad Tatrou sa blýska," which later became the official anthem of the Slovak Republic.

From 1843 to 1847, Štúr worked as a private language expert. In 1844, he wrote Nárečja slovenskuo alebo potreba písaňja v tomto nárečí ("The Slovak dialect or, the necessity of writing in this dialect"). Other Slovak writers, often Štúr's students, began to use the new Slovak language standard. On August 27, he helped start Tatrín, the first national Slovak association.

On August 1, 1845, the first issue of Slovenskje národňje novini ("Slovak National Newspaper") was published. A week later, its literary part, Orol Tatranský ("The Tatra Eagle"), also came out. In this newspaper, written in the new Slovak language, Štúr explained his political ideas. He believed that Slovaks were one nation and deserved their own language, culture, schools, and political freedom within Hungary. He wanted a Slovak Parliament.

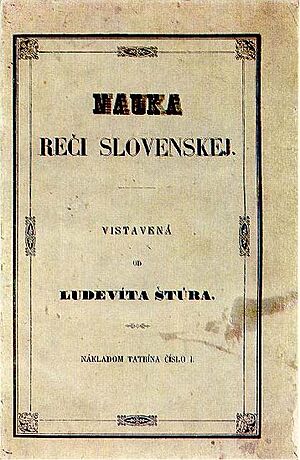

His Time in the Hungarian Parliament

In 1846, Štúr met the wealthy Ostrolúcky family. They helped him become a representative for the town of Zvolen in the Diet of Hungary (Parliament) in Pressburg. He also published his important books Nárečja Slovenskuo alebo potreba písaňja v tomto nárečí and Nauka reči Slovenskej ("The Theory of the Slovak language"). In Nárečia Slovenskuo, he explained why the new Slovak language, based on central Slovak dialects, was needed. In Nauka reči Slovenskej, he explained the grammar of this new language.

In August 1847, at a meeting of the Tatrín association, Catholic and Protestant Slovaks agreed to use only Štúr's new language standard. On October 30, 1847, he became a representative in the Parliament. From November 17, 1847, to March 13, 1848, he gave five important speeches. He asked for an end to serfdom (when peasants were tied to the land), for people to have civil rights, and for the Slovak language to be used in elementary schools. The Parliament ended early in April 1848 because of the 1848 Revolution.

The 1848/49 Revolution

On April 1, 1848, in Vienna, Štúr and his friends started preparing for the Slavic Congress of Prague. On April 20, 1848, he arrived in Prague and gained support from Czech students for his efforts to promote the Slovak language. On April 30, 1848, he helped create "Slovanská lipa" (Slavic lime tree) in Prague, an organization to help Slavs work together.

In May 1848, Štúr helped write an important document called Žiadosti slovenského národa ("Requirements of the Slovak Nation"). This document was read publicly in Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš. In it, Slovaks asked for freedom within Hungary, fair representation in the Hungarian Assembly, and a Slovak Parliament to manage their own region. They also wanted Slovak to be the official language and for schools to use Slovak. They asked for universal suffrage (the right for everyone to vote) and democratic rights like freedom of the press. They also wanted peasants to be freed from serfdom and their lands returned.

However, on May 12, 1848, the Hungarian government issued arrest warrants for the Slovak leaders: Štúr, Hurban, and Hodža. Štúr went to Prague on May 31, 1848, and took part in the Slavic Congress there.

On June 19, 1848, he went to Zagreb, Croatia, and became an editor for a Croatian magazine. With money from some Serbs, he and J. M. Hurban began to plan an uprising against the Hungarian government. The "Slovak Uprising" happened between September 1848 and November 1849.

In September 1848, Štúr went to Vienna to help prepare for the Slovak armed uprising. On September 15–16, 1848, the Slovak National Council was formed in Vienna. This was the main Slovak political and military group, including Štúr, Hurban, and Hodža. On September 19, 1848, in Myjava, the Slovak National Council declared independence from the Hungarian government and called on the Slovak people to start an armed uprising. However, the council only managed to control their local area.

Štúr, Hurban, and others met in Prague on October 7, 1848, to discuss the uprising. When he returned to Vienna in November, Štúr led a group of Slovak volunteers through northern Hungary. On March 20, 1849, he led a group to meet the Austrian king in Olomouc and presented the demands of the Slovak nation. From March to June, Štúr and others talked in Vienna to find a solution for the Slovak demands. But on November 21, 1849, the Slovak volunteer army was officially ended, and a disappointed Štúr went back to his parents' home in Uhrovec.

Later Life

In his later years, Štúr continued his work on language and writing. In late 1850, he tried to get permission to publish a Slovak national newspaper again, but he failed. In December of that year, he went to Vienna to discuss Slovak schools and the Tatrín association.

He also faced personal sadness. His brother Karol died on January 13, 1851. Štúr moved to Karol's family home in Modra to take care of his seven children. He lived there under police watch. On July 27, 1851, his father died, and his mother moved to Trenčín.

In October 1851, he attended meetings in Pressburg about changing the official Slovak language standard. These changes, mainly moving from phonetic (sound-based) spelling to etymological (origin-based) spelling, were later introduced by M. M. Hodža and Martin Hattala in 1851–1852. Štúr helped prepare these changes. The result of these reforms is the Slovak language standard still used today, with only small changes.

In 1852, in Modra, Štúr finished his essay O národních písních a pověstech plemen slovanských ("On national songs and myths of Slavic kin"), which was published the next year. He also wrote his important philosophical book, Das Slawenthum und die Welt der Zukunft ("Slavdom and the world of the future"). In this book, he talked about the difficult situation of Slovaks and suggested working with Russia as a solution.

In 1853, his friend Adela died on March 18. He also went to Trenčín to help care for his sick mother until she died on August 28. His only collection of poems, Spevy a piesne ("Singings and songs"), was published that year. On May 11, 1854, he gave a speech at the unveiling of the Ján Hollý monument in Dobrá Voda. Štúr had also written a poem to honor Ján Hollý.

His Death

On December 22, 1855, Štúr was injured while hunting near Modra. He was supported by his friend Ján Kalinčiak in his last days. On January 12, 1856, Ľudovít Štúr died in Modra. A national funeral was held in his honor.

His Legacy

Ľudovít Štúr has been shown on Czechoslovak and Slovak banknotes throughout the 1900s. He appeared on the Czechoslovak 50 Koruna note in 1987 and on the Slovakian 500 Koruna note since 1993.

The town of Parkan on the Hungarian border was renamed Štúrovo in his honor in 1948.

An asteroid, 3393 Štúr, is named after him. It is about 9.6 kilometers wide and was discovered on November 28 by Milan Antal.

See also

In Spanish: Ľudovít Štúr para niños

In Spanish: Ľudovít Štúr para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |