Æthelwulf, King of Wessex facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Æthelwulf |

|

|---|---|

Æthelwulf in the early fourteenth-century Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England

|

|

| King of Wessex | |

| Reign | 839–858 |

| Predecessor | Ecgberht |

| Successor | Æthelbald |

| Died | 13 January 858 |

| Burial | Steyning then Winchester |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Ecgberht, King of Wessex |

Æthelwulf (which means "Noble Wolf" in Old English) was the King of Wessex from 839 to 858. His father, King Ecgberht, was a powerful ruler. In 825, Ecgberht defeated the King of Mercia, ending Mercia's long control over southern England.

Ecgberht then sent Æthelwulf to Kent. There, Æthelwulf became a sub-king, ruling Kent and other areas. When Æthelwulf became king in 839, he was the first son in a long time to follow his father as King of Wessex. He kept good relations with Mercia, just like his father.

During Æthelwulf's reign, the Vikings were a threat, but he handled them well. He lost a battle in 843 but won a big victory in 851 at the Battle of Aclea. In 853, he helped Mercia in a successful attack on Wales. His daughter, Æthelswith, also married the Mercian king that same year.

In 855, Æthelwulf went on a special trip to Rome. Before he left, he gave away a tenth of his personal wealth to his people. He left his son Æthelbald in charge of Wessex. Another son, Æthelberht, ruled Kent. On his way back, Æthelwulf married Judith, the daughter of the West Frankish king.

When Æthelwulf returned, Æthelbald refused to give up the throne. So, Æthelwulf agreed to divide the kingdom. He ruled the eastern part, and Æthelbald ruled the west. When Æthelwulf died in 858, he left Wessex to Æthelbald and Kent to Æthelberht. However, Æthelbald died two years later, and the kingdom was reunited.

For a long time, historians thought Æthelwulf was too religious and not practical enough. But now, they see him differently. They believe he was a strong king who made his family's power stronger. He was respected by other European rulers and dealt with Viking attacks very well. He is now seen as one of Wessex's most successful kings, setting the stage for his famous son, Alfred the Great.

Contents

Understanding King Æthelwulf's Reign

In the early 800s, most of England was controlled by Anglo-Saxons. Mercia and Wessex were the two most powerful kingdoms in the south. Mercia was the strongest until the 820s. Wessex, however, managed to stay independent.

King Offa of Mercia (757–796) was a very important ruler in the late 700s. King Beorhtric of Wessex (786–802) married Offa's daughter. Beorhtric and Offa forced Æthelwulf's father, Ecgberht, to leave England. Ecgberht spent several years at the court of Charlemagne in Francia.

Ecgberht became king of Wessex in 802. For 200 years, different families had fought for the West Saxon throne. No son had followed his father as king. So, it seemed unlikely that Ecgberht would start a lasting royal family.

Not much is known about Ecgberht's first 20 years as king. He fought against the Cornish people in the 810s. Relations between Mercian kings and the people of Kent were not good. Mercian kings often tried to control Kentish churches.

Viking raids began in the late 700s. But there were no attacks recorded between 794 and 835. In 835, the Isle of Sheppey in Kent was attacked. In 836, Ecgberht lost a battle to the Vikings. But in 838, he defeated a group of Cornishmen and Vikings. This made Cornwall a kingdom under Wessex's control.

Æthelwulf's Family and Life

Æthelwulf's father, Ecgberht, was king of Wessex from 802 to 839. We don't know his mother's name. He had two wives. His first wife, Osburh, was the mother of all his children. She was the daughter of Oslac, a royal official.

Æthelwulf had six known children. His oldest son, Æthelstan, was old enough to become King of Kent in 839. He was likely born in the early 820s. His second son, Æthelbald, was born around 835. He became King of Wessex from 858 to 860.

The third son, Æthelberht, was probably born around 839. He was king from 860 to 865. His only daughter, Æthelswith, married King Burgred of Mercia in 853. The two youngest sons were Æthelred, born around 848, and Alfred, born around 849. Both later became kings.

In 856, Æthelwulf married Judith, the daughter of Charles the Bald, King of West Francia. His first wife, Osburh, had likely died. Æthelwulf and Judith had no children. After Æthelwulf died, Judith married his son, Æthelbald.

Early Years as a Prince

Æthelwulf first appears in historical records in 825. This was when his father, Ecgberht, won the important Battle of Ellandun. This battle ended Mercia's long control over southern England. After this victory, Ecgberht sent Æthelwulf with an army to Kent. Their goal was to remove the Mercian sub-king, Baldred.

Æthelwulf was related to the kings of Kent. He became the sub-king of Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and Essex. He ruled these areas until he became King of Wessex in 839. Records show that King Ecgberht sometimes acted with his son's permission. Æthelwulf even issued his own charters as King of Kent.

Unlike the Mercian rulers, Æthelwulf and his father worked well with the local people in Kent. They appointed local nobles to help govern. This helped them gain support in the region. Historians believe Ecgberht and Æthelwulf rewarded their friends and removed Mercian supporters.

In 829, Ecgberht conquered Mercia. But King Wiglaf of Mercia got his kingdom back a year later. Some historians think this was a setback for Ecgberht. However, others believe Ecgberht might have given Mercia back on purpose. Relations between Wessex and Mercia remained friendly after this.

In 838, King Ecgberht held a meeting in Surrey. Æthelwulf might have been officially made king there by the archbishop. Ecgberht made sure that the church leaders would support Æthelwulf. This helped Æthelwulf become the first son to follow his father as West Saxon king in a long time.

Ecgberht's victories brought him great wealth. This wealth helped him secure the throne for his family. The stable rule of Ecgberht and Æthelwulf led to more trade and farming. This also increased the royal income.

Ruling as King of Wessex

When Æthelwulf became King of Wessex in 839, his time as sub-king of Kent had prepared him well. He also made his own sons sub-kings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says he gave Kent, Essex, Surrey, and Sussex to his son Æthelstan.

However, Æthelwulf did not give Æthelstan as much power as his own father had given him. Æthelstan was called king in charters, but he couldn't issue his own. Æthelwulf visited the south-east often to keep control. He ruled Wessex and Kent as separate areas. Nobles from each kingdom only attended meetings in their own region.

Æthelwulf continued his father's policy in Kent. He governed through local nobles and helped their interests. He gave less support to the church there. In 843, he gave land to Æthelmod, a leading Kentish noble. In 844, he gave land to another noble, Eadred. This created strong ties between the king and his supporters.

Archbishops of Canterbury were firmly under the West Saxon king's influence. Æthelwulf's nobles had high status. They were sometimes listed higher than the king's sons in official documents. Æthelwulf was also known as a supporter of Malmesbury Abbey.

After 830, Ecgberht had kept good relations with Mercia, and Æthelwulf continued this. London, a Mercian town, was under West Saxon control in the 830s. But it returned to Mercian control soon after Æthelwulf became king. The two kingdoms even worked together on coinage in the mid-840s. This shows their friendly relationship.

Berkshire was Mercian in 844, but by 849, it was part of Wessex. King Alfred was born in Wantage, Berkshire, in 849. Cooperation with Mercia continued under King Burgred. He married Æthelwulf's daughter, Æthelswith, in 853. That same year, Æthelwulf helped Burgred attack Wales.

Wessex had strong connections with the Frankish courts in Europe. Æthelwulf even had a Frankish secretary named Felix. This helped Wessex keep good standards in its official documents. Felix was thought to have a lot of influence over the king.

There was an old division between east and west Wessex. The Selwood Forest marked the boundary. Æthelwulf's family had ties to the west. But he focused his support more on the east, especially Winchester, where his father was buried. He appointed Swithun as bishop of Winchester in 852–853.

Dealing with Viking Attacks

Viking raids increased in the early 840s. In 843, Æthelwulf was defeated by 35 Danish ships at Carhampton in Somerset. In 850, his son Æthelstan and a Kentish noble, Ealhhere, won a naval battle against a large Viking fleet near Sandwich. They captured nine ships. Æthelstan is not heard of after this, so he likely died.

The next year, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded five different Viking attacks. A Danish fleet of 350 ships took London and Canterbury. King Berhtwulf of Mercia was defeated when he tried to help. The Vikings then moved to Surrey. There, Æthelwulf and his son Æthelbald defeated them at the Battle of Aclea. The Chronicle said it was the "greatest slaughter of a heathen that we have heard tell of up to the present day."

In 850, a Danish army spent the winter on Thanet. In 853, two nobles were killed fighting Vikings on Thanet. In 855, Danish Vikings stayed over winter on Sheppey. However, during Æthelwulf's reign, Viking attacks were mostly contained. They did not pose a major threat to his kingdom.

Royal Coinage

The silver penny was almost the only coin used in England during this time. Æthelwulf's coins were made at mints in Canterbury and Rochester. Both mints had been used by his father, Ecgberht.

During Æthelwulf's reign, there were four main types of coins. The first Canterbury coins had a design called Saxoniorum. This was later replaced by a portrait of the king. At Rochester, the order was reversed.

Around 848, both mints used a common design. It had "Dor¯b¯" (for Canterbury or Rochester) on one side and "Cant" (for Kent) on the other. Viking raids in 850–851 might have stopped the Canterbury mint. The final coin type, introduced around 852, had a cross on one side and a portrait on the other.

Æthelwulf's coins became less pure (debased) by the end of his reign. This problem got worse after he died. No coins were made by Æthelwulf's sons while he was king.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Ceolnoth, also minted his own coins. Bishops at Rochester also made coins. Historians believe that the mints were quite independent of the royal government. They were part of the stable trading communities in each city.

The Decimation Charters

Æthelwulf's "Decimation Charters" have caused much discussion among historians. Both the historian Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle say that Æthelwulf gave a "decimation" in 855. This was just before he left for Rome. The Chronicle says he gave "the tenth part of his land throughout all his kingdom to the praise of God."

Asser said Æthelwulf "freed the tenth part of his whole kingdom from royal service and tribute." This was for his own soul and his ancestors. Historians debate what this truly meant. It might have been a gift of royal land to churches and nobles. Or it might have been a reduction in taxes for landowners.

Historians have divided these charters into groups. Some are dated 844, and others 854. One from Kent is dated 855, matching the Chronicle's date. Many of these charters are not the original documents. For a long time, many historians thought most of them were fake.

However, in 1994, historian Simon Keynes argued that many of the 854 charters were real. This view is now widely accepted. Historians still debate what the "Second Decimation" of 854 meant.

Some scholars believe it was a gift of royal land (called royal demesne) to churches and nobles. This would have converted the land from folkland (controlled by custom) to bookland (controlled by charter). Booking land was seen as a religious act.

Others think it was a tax cut. It might have reduced the burdens on lands already owned by nobles. This could have encouraged them to help with defense against Vikings. Some historians also suggest it was a religious act to please God during Viking attacks.

Janet Nelson believes the decimation happened in two stages. First in Wessex in 854, then in Kent in 855. This shows that the kingdoms were still separate.

Journey to Rome and Later Life

In 855, Æthelwulf went on a pilgrimage to Rome. Historians believe he was at the peak of his power. It was a good time for him to show his importance among other Christian kings. His older sons, Æthelbald and Æthelberht, were adults. His younger sons, Æthelred and Alfred, were still children.

In 853, Æthelwulf sent his younger sons to Rome. Alfred, and probably Æthelred, were given the "belt of consulship" by the Pope. This created a special link between Alfred and the Pope. Some historians think this trip meant Alfred was meant for the church. Others think Æthelwulf wanted to show his younger sons were worthy of the throne.

Æthelwulf left for Rome in the spring of 855. He took Alfred and a large group with him. He left Wessex to Æthelbald and Kent to Æthelberht. This showed his plan for them to inherit the kingdoms. On the way, they visited Charles the Bald in Francia.

Æthelwulf stayed in Rome for a year. He gave many valuable gifts to the church in Rome. These gifts included a gold crown, gold cups, and silver bowls. He also gave gold to the clergy and silver to the people of Rome. His gifts were very impressive. They showed that he was a wealthy and important king.

Historians wonder why Æthelwulf left his kingdom during a time of Viking attacks. Some think it was for religious reasons. Others believe he wanted to gain prestige. This would help him deal with his adult sons' demands.

On his way back from Rome, Æthelwulf visited Charles the Bald again. On October 1, 856, Æthelwulf married Charles's daughter, Judith. She was only 12 or 13 years old. This marriage was very unusual. Carolingian princesses rarely married foreigners. Judith was crowned queen and anointed by the Archbishop of Rheims. This was the first time a Carolingian queen was definitely anointed.

In Wessex, it was not customary for a king's wife to be called queen or sit on the throne. Asser called this custom "perverse and detestable."

Æthelwulf returned to Wessex to find his son Æthelbald rebelling. Æthelbald tried to stop his father from getting his throne back. Historians have different ideas about why Æthelbald rebelled and why Æthelwulf married Judith.

Some think the marriage was an alliance against the Vikings. It also gave Æthelwulf more prestige. The special status of Judith meant that her son might become king. This could explain Æthelbald's rebellion. Other historians argue that the marriage was Æthelwulf's response to the rebellion. A son by an anointed queen would be a strong candidate for the throne.

Æthelbald's rebellion was supported by some of the king's trusted advisors. Asser said the plot was in the western part of Wessex. Nobles from the west might have supported Æthelbald because Æthelwulf favored eastern Wessex. To avoid a civil war, Æthelwulf agreed to divide the kingdom. He insisted that Judith sit beside him on the throne.

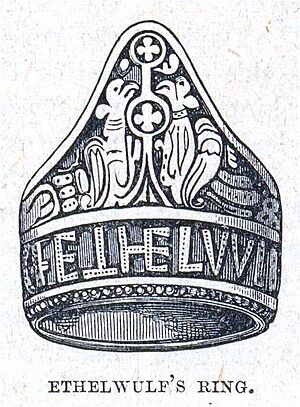

King Æthelwulf's Ring

King Æthelwulf's ring was found in Wiltshire around 1780. It was later given to the British Museum. This ring, and a similar one belonging to his daughter Æthelswith, are important examples of 9th-century metalwork. They show a "court style" of Wessex metalwork.

The ring has "Æthelwulf Rex" (King Æthelwulf) written on it. This shows it belonged to the king. Its design includes two peacocks at the Fountain of Life. This is a Christian symbol for immortality. Many features are typical of 9th-century metalwork. It was likely made in Wessex.

Historians believe the ring was a gift from the king to a loyal follower. It shows the success of kingship in the 9th century. It also connects to the old tradition of kings as "ring-givers."

Æthelwulf's Will and Death

Æthelwulf's will itself has not survived. But his son Alfred's will gives some clues about his father's wishes. Æthelwulf left a special gift to be inherited by whichever of his sons (Æthelbald, Æthelred, and Alfred) lived the longest. Some historians think this meant the survivor would also inherit the throne of Wessex.

Other historians disagree. They believe this gift was only about his personal wealth. They say it was meant to provide for his youngest sons when they grew up. Æthelwulf's movable wealth, like gold and silver, was to be divided among his children, nobles, and for religious purposes.

He also set aside a tenth of his inherited land to feed the poor. He ordered that money be sent to Rome each year. This money was for lighting lamps in St Peter's and St Paul's churches, and for the Pope.

Æthelwulf died on January 13, 858. He was buried at Steyning in Sussex. Later, his body was moved to Winchester, probably by Alfred. As Æthelwulf had planned, Æthelbald became King of Wessex. Æthelberht became King of Kent and the south-east.

Æthelbald then married his stepmother, Judith. This was seen as a "great disgrace" by Asser. Æthelbald died only two years later. Æthelberht then became King of both Wessex and Kent. This meant Æthelwulf's plan to divide the kingdoms was changed. This was likely because Æthelred and Alfred were too young to rule.

After Æthelbald's death, Judith returned to her father. Two years later, she ran away with Baldwin, Count of Flanders. Their son, also named Baldwin, later married Alfred's daughter, Ælfthryth.

How Historians See Æthelwulf

In the 1900s, historians often had a poor view of Æthelwulf. Some thought his trip to Rome showed he was too religious and not practical. They saw his marriage to Judith as foolish. He was often described as a religious man who didn't like war or politics.

However, in the 21st century, historians see him very differently. He is now seen as a king who was not given enough credit. He laid the groundwork for his son Alfred's success. He managed the kingdom's resources well and handled conflicts within his family. He also dealt with neighboring kingdoms effectively.

He strengthened Wessex and expanded its control. He ruled Kent well, working with its local leaders. He gained respect from other European rulers. His trip to Rome increased his prestige. Historians now believe he dealt with Viking attacks more effectively than most other rulers of his time.

See also

In Spanish: Ethelwulfo de Wessex para niños

In Spanish: Ethelwulfo de Wessex para niños