17th Street Canal facts for kids

The 17th Street Canal is a very important waterway in New Orleans. It helps move water from the city into Lake Pontchartrain using a big pump station called Pump Station 6. This canal, along with the Orleans Canal and the London Avenue Canal, are part of the main drainage system for New Orleans. The 17th Street Canal also forms a large part of the border between New Orleans and Metairie, Louisiana. It has also been known as the Metairie Outlet Canal and the Upperline Canal.

Contents

History of the 17th Street Canal

The 17th Street Canal started around the 1850s. It was first dug to create a path for the Jefferson and Lake Pontchartrain Railway. This railway connected the town of Carrollton, Louisiana to a port on Lake Pontchartrain. This was about 8 kilometers (5 miles) long. Most of the land between these two points was swampy back then.

In 1858, another canal was built to help drain the low, swampy area behind Carrollton. This smaller canal connected to the railway canal.

The railway stopped running in 1864 because other train lines were more successful. The city of New Orleans then took over Carrollton. The canal became the boundary line between Orleans Parish and Jefferson Parish. Because it marked the "upper" (up-river) limit of Orleans Parish, it became known as the Upperline Canal.

The smaller canal behind Carrollton was next to a planned street called "17th Street." So, that canal was first called the "17th Street Canal." Later, this name became popular for the larger canal it connected to.

How Pumps Improved Drainage

By the 1870s, a steam engine pump was used to drain the Carrollton neighborhood. It pumped water into the Upperline Canal. As New Orleans grew, more water from the city's streets was pumped into Lake Pontchartrain through this canal. Other canals also connected to the 17th and Upperline Canal system. This helped carry rainwater from many parts of Uptown New Orleans to the lake.

In 1894, "17th Street" was renamed "Palmetto Street." However, people still commonly called the canal by its old name.

A new pumping station opened on the canal in 1899. In the early 1900s, new, very efficient pumps designed by A. Baldwin Wood were installed. These pumps are still used today.

At the start of the 2000s, Pumping Station 6 (also called the Metairie Pumping Station) had 15 pumps. These pumps could move over six billion gallons of water a day! Rainwater from large areas of Uptown New Orleans, Metairie, and nearby neighborhoods flows into the canals. The pumping station then lifts this water into the part of the 17th Street Canal that goes into Lake Pontchartrain.

City Growth Near the Canal

When Station 6 was built, it was at the edge of the developed part of New Orleans. The land closer to the lake was mostly undeveloped swamp. So, it wasn't a big problem if water from the city topped the canal during heavy rains. The water would just flow into the swamp.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, a project created new land along the lakefront. This also built a large levee (a raised barrier) along the lake. However, the swampy land between Metairie Ridge and the new lakefront was not raised. After World War II, many homes were built in the areas along the Canal from Metairie Ridge to the Lake. Because of this, the levees along the "back" sections of the Canal were made taller. The water level in the canal is often much higher than the streets around it.

After Hurricane Betsy, the city needed better flood protection. This led to increasing the size and height of the canal levees to handle storm surges from hurricanes.

In 1998, Hurricane Georges caused Lake Pontchartrain's water level to rise. This pushed lake water into the canal. A report noted that the water came very close to topping the flood wall in at least one spot. Upgrades to the canal levees, flood walls, and bridges began in 1999. The canal was thought to be in good condition before the 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the 17th Street Canal was the largest and most important drainage canal in New Orleans. With Pumping Station No. 6, it could move 9,200 cubic feet of water per second. This was more than the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue Canals combined.

Hurricane Katrina and the Canal Breach

Around 6:30 AM on August 29, 2005, a part of the flood wall on the east side of the 17th Street Canal broke open. This sent huge amounts of water rushing into New Orleans' Lakeview neighborhood. The water level in the canal was about 5 feet lower than the top of the wall when it broke. This was much lower than the wall was designed to handle. The break caused massive flooding that destroyed buildings, homes, and other structures. The initial break grew to be almost 450 feet wide. Thirty-one people died in the areas directly flooded by the 17th Street Canal levee breach.

Why the Canal Failed

Two teams investigated why the flood wall failed. They found that the canal flood wall broke at a much lower water level than its top. This was due to a faulty design. In August 2007, engineers found that some of the remaining flood walls could only safely hold 7 feet of water. This was half of their original design of 14 feet.

In November 2005, a newspaper called the Times-Picayune reported a discovery. Sonar showed that the steel sheets (pilings) holding up the flood wall were 7 feet less deep than they should have been. The pilings were the correct length, but this length was less than the actual depth of the canal. This was a clear engineering mistake. Experts now believe the huge break was caused by this faulty design. It was not just because the storm surge was too high.

An article in 2015 explained that the Army Corps of Engineers misunderstood a test from the 1980s. They thought they only needed to drive the pilings 17 feet deep. But they actually needed to go 31 to 46 feet deep. This decision saved money but made the flood protection much weaker.

Rebuilding After Katrina

The Corps of Engineers built a new, permanent pump station. During a hurricane, a gate will close. This new pump station will work with Pump Station 6. Together, they will block storm surges and lake flooding. In January 2006, the Corps announced that temporary repairs to the broken levee section were done. More permanent repairs would start soon. As a temporary step, they built storm-surge barrier gates and a temporary pump station at the lake end of the canal. In February 2007, a company was hired to increase the pumping power of the 17th Street Canal.

In June 2008, the Corps announced plans to clear private land. This land was needed to access the flood wall and levee. It included backyards along Bellaire Drive on the New Orleans side of the canal. A judge ruled that the Corps could continue. However, property owners could ask for payment for their land. Plans to clear areas on the west (Jefferson Parish) side of the canal began in early 2009.

Some people worried that the temporary pumps were not strong enough. They thought the canal might overflow. But on September 1, 2008, the gates were closed as Hurricane Gustav approached. Both types of pumps worked well for several hours during the storm surge. The gates stayed closed for 18 hours. The pumps ran for 9 hours to keep the city from flooding.

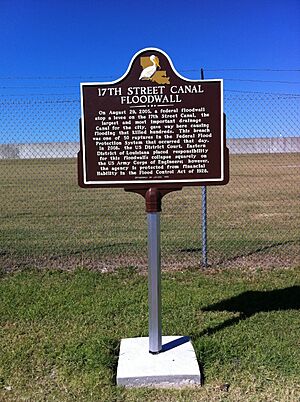

In August 2010, a group called Levees.org placed a plaque at the levee breach site. The Louisiana State Office of Historic Preservation checked the facts on the plaque. It says:

On August 29, 2005, a federal floodwall atop a levee on the 17th Street Canal, the largest and most important drainage canal for the city, gave way here causing flooding that killed hundreds. This breach was one of 50 ruptures in the federal Flood Protection System that occurred that day. In 2008, the US District Court placed responsibility for this floodwall's collapse squarely on the US Army Corps of Engineers; however, the agency is protected from financial liability in the Flood Control Act of 1928.

By 2017, seventeen new Patterson pumps were planned to be working. This is part of the New Orleans Permanent Canal Closures and Pumps (PCCP) project. The 17th Street Canal will get six large pumps and two smaller ones. The large pumps can move 1,800 cubic feet of water per second. This project is designed to handle a "100-year storm," which is a very strong storm that has a 1% chance of happening in any given year.