1968 Washington, D.C., riots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1968 Washington, D.C. riots |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the King assassination riots | |||

A firetruck douses smoldering shops burnt out during the riots

|

|||

| Date | April 4, 1968 – April 8, 1968 | ||

| Location |

Washington, D.C., U.S.

38°55′01″N 77°01′55″W / 38.91694°N 77.03194°W |

||

| Caused by | Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. | ||

| Methods | Rioting, race riots, protests, looting, attacks | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 13 | ||

| Injuries | 1,098 | ||

| Arrested | 6,100+ | ||

The Washington, D.C., riots of 1968 were four days of protests and unrest in Washington, D.C. after the sad death of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. These events were part of bigger protests called the King assassination riots, which happened in over 110 cities across the U.S. The protests in Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Baltimore were some of the largest. President Lyndon B. Johnson sent the National Guard to the city on April 5, 1968, to help the police. In the end, 13 people died, about 1,000 were hurt, and over 6,100 people were arrested.

Why the Protests Happened

Life in D.C. Before 1968

From the late 1800s to the 1960s, many people, including African American families, moved to Washington, D.C. They came for jobs in the U.S. government. This time was known as the Great Migration. While some African American neighborhoods became successful, many poorer areas faced tough living conditions.

Even though racial segregation was legally ended after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, some neighborhoods like Shaw, the Atlas District in Northeast, and Columbia Heights remained important centers for African American businesses.

Unequal Housing in the City

Housing in D.C. was very separated by race. Most of the poor areas were in the southern part of the city, and most people living there were Black. A 1962 report said it was much harder for Black people to find homes than for white people. The homes Black people could find were often in much worse condition.

The report also blamed the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for housing inequality. HUD was also criticized for giving money to buildings that did not allow Black people to live in them.

Challenges in Education

Because of housing separation, schools in Black neighborhoods often received less money. This was due to lower property taxes in those areas. Many white parents sent their children to private schools.

About two-thirds of D.C.'s population was Black, but 92% of public school students were Black. Statistics showed that only one out of three Black ninth-grade students graduated. This caused a lot of frustration among the Black community. The government gave $5.5 million for schools, but none of it went to schools with mostly Black students.

Police and Community Tension

Before 1968, there was growing tension between the police and the Black community. About 80% of the D.C. police force was white, while 67% of the city was Black.

Police tactics used in the South to control civil rights protests made Black people in inner cities across the country more afraid of the police. In the years before 1968, there were many times when D.C.'s Black community protested against white police officers. For example, in 1965, two white D.C. police officers arrested a group of Black boys, aged 12 to 16, for playing basketball. This led to Black crowds gathering around police stations, throwing rocks and firecrackers.

To improve things, three programs were started:

- A police-run Department of Community Relations.

- A civilian-run Advisory Council for each police area.

- A Complaint Review Board made of civilians to review complaints.

Still, in 1968, a Black D.C. reverend said that relations between Black residents and white police had reached a "danger point."

High Unemployment Rates

In June 1967, the national unemployment rate was 4% for white Americans and 8.4% for non-white Americans. In D.C., the unemployment rate for non-white people was often over 30% during the 1960s. This was much higher than the national rates.

Events of the Riots

Looting and Fires Begin

On the evening of Thursday, April 4, news of King's death in Memphis, Tennessee spread. Crowds started gathering at 14th and U Streets. Stokely Carmichael, a civil rights activist, led people to stores, asking them to close. The crowd soon became out of control and began breaking windows. Carmichael, who supported the protests, told people to "go home and get your guns."

The unrest began when a window was broken at a drug store. By 11 p.m., window-smashing and looting spread. The local police could not handle the situation. By 3 a.m., 200 stores had broken windows, and 150 stores were looted. Some Black store owners wrote "Soul Brother" on their shops to protect them.

The D.C. Fire Department reported 1,180 fires between March 30 and April 14, 1968, as people set buildings on fire.

Carmichael's Speeches

The next morning, Mayor-Commissioner Walter Washington ordered the damage cleaned up. However, anger was still high. At 10 a.m., Stokely Carmichael spoke at a rally. He said, "white America has declared war on black America." He also said, "Black people have to survive, and the only way they will survive is by getting guns."

He added, "White America killed Dr. King last night. She made a whole lot easier for a whole lot of black people today. There no longer needs to be intellectual discussions, black people know that they have to get guns." He believed Dr. King was the one person trying to preach peace.

Clashes with Police

Protesters on 7th Street NW and in the Atlas District had violent clashes with police. Around midday, buildings were set on fire. Firefighters were attacked with bottles and rocks, making it hard to put out the fires. By 1 p.m., the protests were intense again. Police tried to control the crowds with tear gas, but it did not work.

President Johnson's Response

After King's death was announced, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked everyone not to use violence. The next morning, he met with Black civil rights leaders. He asked citizens to "deny violence its victory" and keep King's dream alive. He declared the Sunday of that week a day of mourning for Martin Luther King Jr. He also ordered all American flags to be flown at half-staff. Finally, he decided to send in the military to stop the unrest.

Mayor Walter Washington's Efforts

Walter Washington made nightly appearances during the protests. Many people in the city believed his presence helped calm the violence. He also refused FBI director J. Edgar Hoover's orders to shoot at protesters. Washington said it would cause needless harm to civilians. In 1974, Washington became the city's first elected mayor and its first Black mayor.

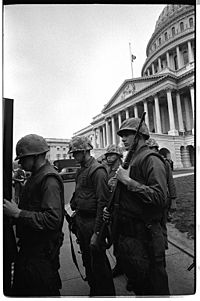

Military Steps In

On Friday, April 5, President Johnson sent 11,850 federal troops and 1,750 D.C. Army National Guard members. They helped the overwhelmed D.C. police force. Marines placed machine guns on the steps of the Capitol. Army soldiers guarded the White House.

At one point, on April 5, the protests came within two blocks of the White House before people moved back. This military presence in Washington was the largest in any American city since the Civil War.

Federal troops and National Guardsmen set a strict curfew. They worked to control the protests, patrolled streets, guarded looted stores, and helped those who were displaced. They stayed in the city even after the protests ended to prevent more trouble.

Lives Lost

By Sunday, April 7, the city was mostly calm. However, 13 people had died from fires, by police officers, or by protesters. Another 1,097 people were hurt, and over 7,600 people were arrested.

| Name | Race | Gender | Age | Cause of death | Location of death | Date of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Marvin Fletcher | White | Male | 28 | Killed in confrontation | Gas station near 14th and U Street, NW | Thursday, April 4, 1968 |

| Unidentified teenager | Black | Male | 14~ | Killed in fire | G.C Murphy Store, 3128 14th Street, NW | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| George W. Neely | Black | Male | 18 | Killed in fire | G.C Murphy Store, 3128 14th Street, NW | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Unidentified teenager | Black | Male | 14–17 | Killed in fire | Morton's store, 7th and H Streets | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Vincent Lawson | Black | Male | 15 | Killed in fire | Warehouse at 653 H St. NE | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Harold Bentley | Black | Male | 34 | Killed in fire | 513 8th Street, NE | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Thomas Stacey Williams | Black | Male | 15 | Shot by policeman | Near 42nd Street, NE | Friday April 5, 1968 |

| Ernest McIntyre | Black | Male | 20 | Shot by policeman | 4009 South Carolina Ave. SE | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Annie James | Black | Female | 52 | Smoke inhalation from fire | Apartment above Quality Clothing Store at 701 Q St. NW | Friday, April 5, 1968 |

| Ronald James Ford | Black | Male | 29 | Bled to death after slashing neck and chest | Outside Cardozo High School on 13th Street NW | Saturday, April 6, 1968 |

| Cecil Hale ‘Red Rooster’ | Black | Male | 40~ | Smoke inhalation from fire | Carolina Market, 1420 7th Street, NW | Sunday, April 7, 1968 |

| William Paul Jeffers | Black | Male | 40 | Killed in fire | Jan's Drygoods Store, 1514 7th Street, NW | Sunday, April 7, 1968 |

| Fred Wulf | White | Male | 78 | Found unconscious, allegedly beaten | Sidewalk at New Jersey and H streets | Monday, April 8, 1968 |

After the Protests

The Civil Rights Act of 1968

On April 11, 1968, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. This law included the Fair Housing Act. This part of the law made it illegal to discriminate when selling, renting, or financing homes based on a person's race, religion, national origin, or gender.

Johnson sped up the process of passing this law after Dr. King's death. The Act helped to end segregation in D.C. and reduced the number of Black people living in separate, poorer areas.

Rebuilding the City

Fauntroy's Plan for Recovery

Walter Fauntroy, a city leader and head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, played a big part in rebuilding D.C. after the 1968 protests. When the protests began, Fauntroy spoke about his sadness over Dr. King's death. He asked people to "Handle your grief the way Dr. King would have wanted it."

After the protests, Fauntroy suggested a plan. It would let property owners build bigger buildings if they also spent money on community projects. These projects included housing, apartment repairs, or new shopping centers. If someone wanted to start a business project, they first had to promise to do a local community project. They would also need to give back 50% of the extra money they earned from the program. Fauntroy thought this plan could bring in an extra $500 million for the city.

Damage and Changes in the City

The protests caused a lot of damage. About 1,199 buildings were damaged, including homes and businesses. The estimated loss for insured properties was $25 million. However, insurance only covered 29% of the total loss. Many insurance policies were canceled, and some businesses had to pay much higher insurance rates. The city also lost about $40 million in tourism.

The protests badly hurt Washington's inner city economy. Many jobs were lost, and insurance costs went up. People became worried, and many white families moved out of the city. This caused property values to drop. Crime also increased in the damaged neighborhoods, which made it even harder for new businesses to invest there.

On some blocks, only ruins remained for many years. Areas like Columbia Heights and the U Street Corridor only started to recover economically much later. This recovery began when metro (subway) stations opened in those areas in the 1990s.

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |