3rd Bengal Light Cavalry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry |

|

|---|---|

Flag of the East India Company

|

|

| Active | 1797–1857 |

| Country | British India |

| Allegiance | East India Company |

| Branch | Bengal Army |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Role | Light cavalry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | Meerut Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Meerut |

| Distinguishing colours | Orange facings |

| Engagements | Second Anglo-Maratha War First Anglo-Afghan War First Anglo-Sikh War Indian rebellion of 1857 |

| Battle honours | Delhi 1803 Leswarree Deig Bhurtpore Affghanistan 1839 Ghuznee 1839 Aliwal Sobraon |

The 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry was a special army group in the East India Company's Bengal Army. It was made up of soldiers from India. This group, also known as the 3rd Bengal Native Cavalry, was formed in 1797.

The regiment fought in many important battles across British India. They showed great bravery in wars like the Second Anglo-Maratha War and the First Anglo-Afghan War. They also fought in the First Anglo-Sikh War, earning special awards for their service.

In April 1857, a big problem started. Many soldiers in the regiment refused to use new rifle cartridges. They were put on trial and sent to prison. After this, their friends in the regiment broke them out of jail. This event led to the start of the Indian Mutiny when they marched to Delhi. Because of the mutiny, all Bengal Light Cavalry regiments were later closed down.

Contents

History of the Regiment

Forming the Cavalry Group

In 1796, the East India Company decided to create new cavalry groups. They asked the Governor-General, John Shore, to form four new regiments. So, in 1797, the 3rd Bengal Native Cavalry was started in a place called Oude.

At first, people used different names for the group, like "Bengal Native Cavalry" or "Bengal Light Cavalry." But by 1857, it was officially known as the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry.

Brave Battles and Awards

The 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry fought well in the Second Anglo-Maratha War. They took part in the Battle of Delhi and the Battle of Laswari in 1803. For their courage, they received a special flag that said "Lake and Victory." They also earned battle honors like "Delhi 1803" and "Leswarree."

The regiment was also part of the Siege of Bharatpur in 1825–1826. They helped in the final attack on the fort and earned the "Bhurtpore" battle honor. Later, in 1839, they fought in the First Anglo-Afghan War at the Battle of Ghazni. This earned them more honors: "Affghanistan 1839" and "Ghuznee 1839."

During the 1845–1846 First Anglo-Sikh War, the regiment fought in the Battle of Aliwal and the Battle of Sobraon. They received battle honors for both of these important fights.

The Meerut Incident

New Rifles and Rumors

By 1857, the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry had been in Meerut for three years. The East India Company planned to give its Indian soldiers new Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles. These rifles used a new type of paper cartridge. To load the rifle, soldiers had to bite open the cartridge.

Rumors quickly spread that the grease on these cartridges was made from pig fat and cow fat. This was a big problem because pig fat was offensive to Muslim soldiers, and cow fat was offensive to Hindu soldiers. These rumors made many soldiers very upset.

The Refusal to Use Cartridges

The officer in charge, Lieutenant Colonel George M. Carmichael-Smyth, heard about the rumors. He changed the loading drill so soldiers would tear the cartridges by hand, not bite them.

On April 23, Carmichael-Smyth announced a practice parade for the next day. Soldiers would use their old muskets and ammunition, not the new ones. But that evening, the soldiers decided they would not accept any cartridges. They worried that using any cartridge would make it seem like they accepted the "bad" ones.

The next morning, 90 soldiers, called carabiniers, lined up for the drill. But none of them took their ammunition. Even after Carmichael-Smyth explained that these were the old cartridges, 85 out of 90 men refused the order.

The Trial and Punishment

A group of Indian officers investigated the refusal. They found that the cartridges were indeed the old type. The soldiers' main concern was not the grease itself, but the fear of being seen as having used the "bad" cartridges. The inquiry decided the soldiers had no good reason to refuse.

So, a court martial (a military trial) was held. It was made up entirely of Indian officers. All 85 soldiers pleaded "not guilty." But 14 out of 15 officers found them guilty of disobeying orders. They were sentenced to 10 years of hard labor. The judges asked for mercy, saying the men were good soldiers who had been misled. But this was ignored.

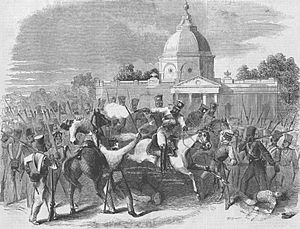

On May 9, 1857, a large parade was held to announce the sentences. The convicted soldiers were stripped of their uniforms and put in shackles. The other soldiers watched, but no one helped them. After about two hours, the shackled soldiers were taken to jail. The military leaders thought everything was calm, but warnings of trouble began to spread.

The Mutiny Begins!

Chaos in Meerut

The very next day, Sunday, around 6:00 PM, trouble broke out in Meerut. Smoke was seen rising from burning buildings. Soldiers from the 60th Rifles were getting ready for church when they heard gunfire. They quickly armed themselves.

Mounted soldiers from the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry attacked them. But when they saw the 60th Rifles were ready, they rode away. They went straight to the jail and freed their friends with the help of a local blacksmith. At the same time, other Indian regiments also rebelled. They harmed some officers and civilians, and set many buildings on fire.

One small group of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, about 80 to 90 men, stayed loyal to their officers. But most of the mutinying soldiers, after freeing their comrades, joined in the chaos in Meerut. Then, the rebels from all three regiments left Meerut and headed towards Delhi. The military leaders in Meerut didn't realize they had left until the next morning.

The March to Delhi

Around 9:00 AM on May 11, a group of cavalry was seen approaching Delhi from Meerut. East India Company officials quickly realized something was wrong. They tried to contact Meerut by telegraph, but the line was cut.

The 54th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry was ordered to stop them. But when officials went to secure a gate at Delhi's Red Fort, they found soldiers from the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry had already taken control. A fight broke out. A small group from the regiment went to the city's jail and freed the prisoners without any trouble.

The main group of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry then arrived. They entered the fort and caused harm to civilians inside. A small group even went to the private area of Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor, and asked him to lead them. The regiment spread out, and soon other Indian soldiers in Delhi joined the rebellion. There was widespread looting, burning, and harm to East India Company employees and shopkeepers. This was the true start of the Indian Mutiny.

After the Mutiny

The mutineers of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry stayed in Delhi until the Siege of Delhi ended in September 1857. They then moved to Lucknow, and later to Nepal. Many of them died there from fighting, sickness, or hunger. Those who eventually made it back home were often avoided by their communities because of their part in the mutiny. The 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, like all other Bengal Light Cavalry regiments, was officially closed down after the Indian Mutiny.

What People Thought Later

Criticism of the Leaders

Many people later criticized how the situation was handled. Carmichael-Smyth's decision to hold the parade was immediately questioned by his boss, William Hewitt. Hewitt felt that if the parade hadn't happened, the cartridge issue "would have blown over."

Another officer, Lieutenant John Campbell MacNabb, also thought the parade was unnecessary. He believed the soldiers' dislike for their commanding officer made things worse. Hewitt himself was criticized for how he announced the sentences on May 9. Later, Hewitt and another officer, Archdale Wilson, blamed each other for what happened. Hewitt lost his command of the Meerut Division.

A Different View

However, not everyone agreed with the criticism. Field Marshal Frederick Roberts, a famous military leader, wrote in his 1897 book that he doubted anything could have stopped the mutiny. He said the cavalry available was not ready to chase the mutineers.

Roberts believed that the Indian soldiers had already decided to rebel against the British. He felt that the events at Meerut were just a matter of "when and how" the mutiny would start, not the cause of it. He thought no quick action by the Meerut leaders could have stopped it.

See also

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |