Abel Gance facts for kids

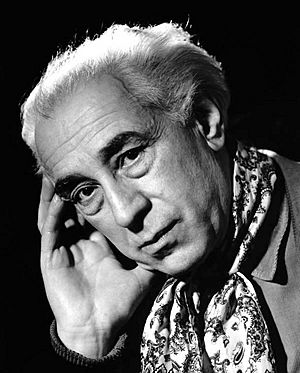

Abel Gance (French: [gɑ̃s]; born Abel Eugène Alexandre Péréthon; 25 October 1889 – 10 November 1981) was a famous French film director, producer, writer, and actor. He was a true pioneer in filmmaking, especially known for his creative editing techniques. He is most famous for three big silent films: J'accuse (1919), La Roue (1923), and Napoléon (1927).

Contents

Abel Gance: A Film Pioneer

Early Life and Dreams

Abel Gance was born in Paris, France, in 1889. His mother was Françoise Péréthon, and his father was a doctor named Abel Flamant. For his first eight years, Abel lived with his grandparents in a town called Commentry. Later, he moved back to Paris to live with his mother. She had married Adolphe Gance, a mechanic, and Abel took his last name.

Abel left school when he was 14. He loved reading and art, and he taught himself a lot throughout his life. He first worked as a clerk, but soon he started acting in the theatre. When he was 18, he got a job at a theatre in Brussels, where he became friends with actor Victor Francen and writer Blaise Cendrars.

Starting in Silent Films

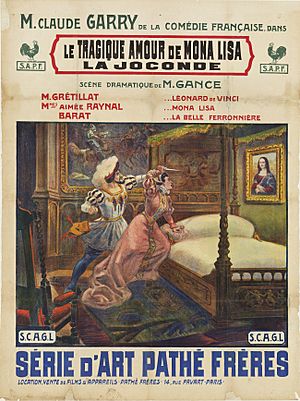

While in Brussels, Abel Gance started writing film stories. He sold his first ones to Léonce Perret. In 1909, he acted in his first film, Molière, directed by Perret. At first, Gance thought movies were "childish," but he needed the money. He kept writing film stories and often sold them to Gaumont.

He later got sick with tuberculosis, a serious illness at the time. After resting, he recovered. With some friends, he started his own film company, Le Film Français. In 1911, he began directing his own movies. His first was La Digue (ou Pour sauver la Hollande), a historical film. It was the first movie appearance for the famous artist Pierre Renoir.

Gance also tried to stay involved with theatre. He wrote a very long play, but it was five hours long, and he refused to make it shorter.

Innovations During World War I

When World War I began, Gance could not join the army because of his health. In 1915, he started working for a new film company called Le Film d'art. He quickly became known for his experimental films. One of his early films, La Folie du docteur Tube, was a funny fantasy. In it, he and his cameraman Léonce-Henri Burel used special mirrors to create amazing visual effects. The film producers were not happy and refused to show it.

Despite this, Gance continued making films for Film d'Art until 1918. He made more than a dozen successful movies. He experimented with many new techniques, like moving the camera (tracking shots), showing very close-up images (extreme close-ups), filming from low angles, and splitting the screen into multiple images.

His film J'accuse (1919) was very important. Gance joined the army's film service to film scenes on a real battlefield. This movie showed the sadness and destruction of the war. It had a strong impact and was shown all over the world.

The Epic La Roue

In 1920, Gance started his next big project, La Roue. He was recovering from the Spanish flu at the time. The film was also affected by the illness of his friend and lead actor, Séverin-Mars, who sadly died after the film was finished.

Gance put a lot of energy and creativity into La Roue. The story was set first in busy railway yards and then in the snowy Alps. He used advanced editing methods and very fast cutting, which influenced many other directors. The original film was incredibly long, almost nine hours! It was later cut down for general release. Today, a restored version is nearly seven hours long.

The Grand Napoléon

After a short break with a comedy film called Au Secours! (1924) starring Max Linder, Gance began his most ambitious project: a six-part film about the life of Napoléon. Only the first part was completed. It covered Napoleon's early life, through the French Revolution, and up to his invasion of Italy. This film was huge, with carefully recreated historical scenes and many characters.

Napoléon was full of new film techniques. Gance used fast editing, cameras held by hand, and images placed on top of each other (superimposition). For wide-screen scenes, he used a system called Polyvision. This needed three cameras and three projectors to create a huge panoramic effect. In the final scene, the outer two screens were colored blue and red, making a giant French flag! The original film was about six hours long. A shorter version was shown in Paris in 1927 to a very important audience, including the future General de Gaulle. This film became Gance's most famous work.

The Sound Era and Later Years

When sound came to movies, Gance was excited. His first sound film was La Fin du monde (1931). It was an expensive science-fiction movie about a comet hitting Earth. Gance himself played the main role. However, the film was not successful, and after this, Gance had less freedom to make the films he wanted.

Gance continued to make many films in the 1930s. He often said he made these films "not in order to live, but in order not to die," meaning he made them to keep working. Some of his films from this time include Lucrezia Borgia (1935) and Un Grand Amour de Beethoven (1937). He also made a new version of J'accuse! (1938). This was not just a remake, but a warning about the new war he saw coming.

During World War II, after the Fall of France in 1940, Gance made a popular drama called Vénus aveugle. He saw this film as a message of hope for the French people during a difficult time. Gance supported Philippe Pétain at this time, who was seen by some as a leader who could save the country.

After making one more film, Le Capitaine Fracasse, Gance went to Spain in 1943. He stayed there until 1945, due to growing problems with the German authorities in France.

After the war, it became harder for Gance to get support for his film projects, so he made fewer movies. His historical drama La Tour de Nesle (1954) was his first film in color. This film helped bring new interest to his work, and some critics, like François Truffaut, praised Gance as a brilliant but overlooked director.

Gance returned to big historical films with Austerlitz (1960) and Cyrano et d'Artagnan (1963). Later, he worked on historical subjects for television.

Throughout his life, Gance kept going back to his film Napoléon. He often edited it into shorter versions, added sound, and sometimes filmed new scenes. Because of this, the original 1927 film was not seen for many years. However, a film historian named Kevin Brownlow worked hard to reconstruct a five-hour version of the film. This version was shown at a film festival in 1979, with the 89-year-old Gance attending. This event brought Gance much-deserved recognition, and further restorations made his name known around the world.

Abel Gance was married three times. He passed away from tuberculosis in Paris in 1981 at the age of 92. He is buried in the Cimetière d'Auteuil in Paris.

Gance's Legacy in Film

Abel Gance wanted to be known as "the Victor Hugo of the screen," comparing himself to a famous French writer. Many people recognize his films for their big ideas, cleverness, and romantic style. Some critics have noted that his work sometimes mixed amazing creativity with simple or less impressive parts.

One thing everyone agrees on is Gance's many new ideas in filmmaking. Besides his multi-screen Polyvision, he used techniques like layering images, extreme close-ups, and fast, rhythmic editing. He also moved the camera in unusual ways – holding it by hand, putting it on wires or a swing, or even strapping it to a horse! He also experimented early with adding sound to films, and with filming in color and 3-D. He tried almost every film technique he could think of. Other directors, like Jean Epstein and later the French New Wave filmmakers, were influenced by him. Film historian Kevin Brownlow said that with his silent films J'accuse, La Roue, and Napoléon, Abel Gance used the film medium more fully than anyone before or since.

Some critics have also discussed the political messages in Gance's films. While J'accuse (1919) seemed to show his anti-war feelings, reactions to Napoléon (1927) were more mixed. Some thought it supported dictatorships. This idea that Gance had conservative political views continued in later discussions of his work. People also noted his strong support for Philippe Pétain during World War II and later for Charles de Gaulle. However, others believe that Gance's amazing ability to create grand, exciting spectacles, often with a focus on France, is more important than his politics. As one obituary said, "Abel Gance was perhaps the greatest Romantic of the screen."

Jury Member

Abel Gance was a judge for Miss France 1938.

He was also a judge for the 1953 Cannes Film Festival, where Jean Cocteau was the president of the jury.

Filmography

See also

In Spanish: Abel Gance para niños

In Spanish: Abel Gance para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |