Africville facts for kids

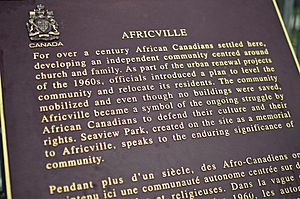

Africville was a small community in Halifax, Canada, where mostly African Nova Scotians lived. It was located on the southern shore of the Bedford Basin and existed from the early 1800s until the 1960s. Today, it is a special place that remembers the community, with a museum built there.

Africville was started by Black Nova Scotians from different backgrounds. Many of the first people to settle there were formerly enslaved African Americans. They were Black Loyalists who gained their freedom from the British during the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Later, other Black people moved to Africville, often for jobs in mining.

During the 1900s, the city of Halifax did not provide basic services to Africville, like proper roads, clean water, or sewage systems. The city also used the area for dirty industries, even putting a garbage dump nearby in 1958. Because of this, Africville residents faced poverty and poor health. In the late 1960s, the City of Halifax decided to move everyone out of Africville. They wanted to build a bridge, highways, and port facilities. After the residents were moved, many former residents and activists started protesting the way they were treated.

In 1996, Africville was named a National Historic Site of Canada. This recognized it as an important place for Black Canadian history and a reminder to protect communities. After many years of protests, the Halifax Council agreed in 2010 to apologize to the families who were forced to leave. They also set up the Africville Heritage Trust to build a museum and a copy of the community's church.

Contents

Discovering Africville's Past

Africville is known as one of the first free Black communities outside of Africa, similar to other settlements in Nova Scotia.

How Africville Started

Africville was first called the "Campbell Road Settlement." It began as a small, self-sufficient community of about 50 people in the 1800s.

The first settlers were Black Loyalists. These were formerly enslaved people from the Thirteen Colonies who escaped during the American Revolutionary War. The British promised them land and freedom in Nova Scotia. Later, more Black refugees from the War of 1812 also settled there.

In 1836, Campbell Road was built, making it easier to reach the area. The Seaview African United Baptist Church was built in Africville in 1849 by clergyman Richard Preston. This church became very important to the community.

The first land sales in Africville were recorded in 1848. The first two landowners were William Arnold and William Brown. In the late 1850s, the Nova Scotia Railway was built, cutting through Africville.

The community became known as 'Africville' around 1900. Some people thought the name meant residents came from Africa, but this was not true. It was simply the part of Richmond (Northern Halifax) where Black families lived.

Another railway line was added in 1906, and more tracks were built later. Trains ran through the area all the time.

The Halifax Explosion's Impact

At its busiest, Africville had about 400 people. In 1917, the Halifax Explosion happened. High land to the south protected Africville from the worst of the blast, which destroyed the nearby community of Richmond. However, Africville still suffered a lot of damage.

After the explosion, Africville received very little help from the city. Other parts of Halifax were rebuilt and modernized, but Africville was not. More people moved to Africville in the early 1900s, looking for jobs in nearby industries.

Life in Africville

Working and Earning

Life was often hard for the first two generations in Africville. Many men found low-paying jobs. Some worked as seamen or Pullman porters, cleaning and working on train cars. This train work was seen as a good job because it was steady and allowed them to travel. About 35% of workers had regular jobs, and 65% worked as house servants. Women also worked as cooks or cleaners in hospitals and homes.

Learning and School

The community's education was often overlooked. The city built the first elementary school in Africville in 1883, but the community had to pay for it. Because it was a poor community, teachers often did not have formal training until 1933. Only about 40% of children went to school. Many families needed their children to help with paid work or care for younger siblings. Out of 140 children, only a few reached grade 7 or 8, and even fewer reached grade 10.

The Heart of the Community: The Church

The church was the center of life in Africville. The Seaview African United Baptist Church was founded in 1849. It joined with other Black Baptist churches to form the African Baptist Association in 1854. All social life revolved around the church, including baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Other Black groups would visit Africville for Sunday picnics and events. Everything, from clubs to youth groups and Bible classes, was done through the church.

Playing Hockey

The Africville Seasides hockey team was part of the pioneering Colored Hockey League (1894–1930). They won championships in 1901 and 1902. The team was led by their star goalie, William Carvery, and included his two brothers and three Dixon brothers.

Africville and Halifax City

Africville was often isolated from the rest of Halifax. The community never received proper roads, health services, clean water, streetlights, or electricity. Residents asked the city for these services, but they were not provided. The lack of services caused serious health problems. Wells were often dirty, so residents had to boil their water before drinking or cooking.

From the mid-1800s, the City of Halifax placed its least wanted facilities near Africville. This happened because the people of Africville had little political power and their land was not considered valuable. A prison was built there in 1853, and a hospital for infectious diseases in 1870. A slaughterhouse and a place for waste were also built nearby.

In 1958, the city moved the main garbage dump to the Africville area. Residents knew they could not stop this. The dump made the city officially call Africville a "slum."

The Razing of Africville

In the 1940s and 1950s, governments across Canada worked on "urban renewal" projects. This meant tearing down areas seen as slums and moving people to new housing. The goal was to use the land for businesses and industries. Other Black neighborhoods were also destroyed this way, like The Ward in Toronto.

Discussions about moving Africville residents happened as early as 1947, after a fire destroyed several homes. But serious plans for relocation did not start until 1961. In 1962, the Halifax City Council voted to move the residents.

Moving and Demolishing Homes

The official move happened mostly between 1964 and 1967. Residents and their belongings were moved by Halifax garbage trucks. This image deeply hurt the community, showing how poorly they felt treated. Many former residents believe the city just wanted to remove Black people from Halifax, not truly use the land for industry. They felt the city let Africville fail so they could then destroy it.

The relocation caused many problems, including suspicion and jealousy. Only 14 residents had clear legal ownership of their land. Those without legal rights were given $500 and promises of money for furniture, social help, and public housing. Young families thought they had enough money for a new start. But most older residents did not want to leave their homes. They felt cheated and sad. It became harder to resist as more residents accepted money and their homes were torn down.

The city quickly tore down each house as soon as people moved out. Sometimes, they would demolish a house when a resident was away, like in the hospital. On November 20, 1967, the Africville church was torn down at night to avoid arguments. This happened a year before the city officially owned the building. There is controversy because documents show the church was sold in 1968, but the date was changed by hand to 1967. City papers show the demolition order was sent in 1967, claiming the building was unsafe. But residents remember the church being bulldozed in 1967, right after its last service. Important records like birth, marriage, and death certificates were inside and were destroyed. These records could have helped families prove land ownership.

The very last home in Africville was torn down on January 2, 1970.

Life After Africville

After moving to public housing in the city, former residents faced new problems. The cost of living went up, and more people became unemployed. The city's promises of jobs and education programs were not kept. Benefits were so small they barely helped. Within a year and a half, the relocation program had failed.

Family stress and debt forced many to rely on public assistance. People felt anxious and upset. A big complaint was that they felt no pride or ownership in the "sterile public housing projects."

Africville's Lasting Impact

Part of Africville's former land is now a highway interchange for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. The port development did not reach Africville's historic waterfront, so it remains untouched.

Because of the controversy, the city of Halifax created Seaview Memorial Park on the site in the 1980s to protect it. For many years, the park was often used as a dog park. Eddie Carvery has lived on the Africville site since 1970 to protest the destruction, even though city officials have removed his trailers many times. Former Africville residents also held protests at the park throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

The Africville Genealogy Society was formed in 1983 to find former residents and their families. In 2002, Halifax mayor Peter Kelly offered land and money to build a replica of the Seaview African United Baptist Church. The Africville Genealogy Society asked for more land and the chance to build affordable housing nearby. The area that was once Africville was declared a national historic site in 2002.

The Africville Apology

In May 2005, New Democratic Party of Nova Scotia politician Maureen MacDonald introduced a bill called the Africville Act. This bill asked for a formal apology from the Nova Scotia government. It also asked for public hearings about Africville's destruction and a fund to preserve the land and help former residents and their families.

On February 23, 2010, the Halifax Council approved the "Africville apology." They worked with the Government of Canada to create a $250,000 Africville Heritage Trust. This trust would design a museum and build a copy of the community church. The dedicated site was about 2.5 acres (1 hectare). On February 24, 2010, Halifax Mayor Peter Kelly officially apologized for the eviction. This was part of a $4.5 million compensation deal. The city also changed the name of Seaview Park back to Africville at the annual Africville Family Reunion on July 29, 2011.

The Africville Museum

A building designed to look like the Seaview African United Baptist Church was built in the summer of 2011. It now serves as a museum and historical center. The church was officially opened on September 25, 2011, with a gospel concert and church services. An album of old Africville songs was also released.

Since then, the Museum has offered tours, put on exhibits, and organized fundraisers. It continues to face challenges, like local residents still using the park for dogs and vandals damaging signs.

A lawsuit has been filed to seek individual payments for property in Africville.

Tributes and Media

The story of Africville has inspired many artists and creators.

Music Inspired by Africville

- African Canadian singer/songwriter Faith Nolan released an album called Africville in 1986.

- Africville Suite (1996) is an album by jazz pianist Joe Sealy. It has twelve songs about places and activities in Africville, where Sealy's father was born. The album won a Juno Award in 1997.

- Ain't No Thing Like a Chicken Wing (1997) by Canadian jazz pianist Trevor Mackenzie is a tribute to the neighborhood where his father grew up.

- "A Nourishment by Neglect" (2007) by the band Bucket Truck has a video that tells the story of Africville's destruction.

- In 2007, Canadian hip-hop group Black Union released a song about Africville with Maestro. The music video was filmed in Africville Park.

Films About Africville

- Remember Africville (1991) is a documentary film by the National Film Board of Canada. It won an award for best documentary.

- Stolen From Africville (2008) is a documentary that follows the lives of those displaced from Africville.

- Africville: Can't Stop Now (2009) is a documentary that shows how the community survived despite losing its home.

Books and Plays

- Consecrated Ground (1998) is a play by George Boyd about the Africville eviction. It was nominated for a major award.

- Last Days in Africville (2006) by Dorothy Perkyns is a fictional story about a young girl in Africville during its destruction.

- The story of Africville has influenced the work of writer George Elliott Clarke.

- The Children of Africville (2007) by Christine Welldon is a children's book about the kids growing up in Africville before it was destroyed.

- The Hermit of Africville (2010) is a biography about Eddie Carvery, the longtime Africville protester.

- Big Town (2011) by Stephens Gerard Malone is a novel about the eviction and razing of Africville.

- Africville (2018) is a book by Shauntay Grant.

- Africaville (2019) by Jeffrey Colvin is a novel that explores three generations connected to the community.

Other Tributes

- In 1989, a historical exhibit about Africville traveled across Canada. It is now a permanent exhibit at Nova Scotia's Black Cultural Centre.

- In 2012, the Africville Heritage Trust created an educational kit called "Out Home: Africville." This kit helps students learn about the story of Africville.

- In 2020, a student named Danielle Mahon created an online project called Mapping Memories of Africville. It shows public records and interviews from former residents on a map of the old Africville site.

Notable Residents

- Addie Aylestock – a church deaconess

- Eddie Carvery – a longtime protester at the Africville site

- George Dixon (boxer) – a famous boxer

- Ricky Anderson

- Edith Hester McDonald-Brown

See Also

- Viola Desmond – a Nova Scotia woman who fought for civil rights

- Nova Scotia Heritage Day

- Black Nova Scotians

- Joan Jones

Images for kids

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |