Puerto Rican amazon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Puerto Rican amazon |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Amazona

|

| Species: |

vittata

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

The Puerto Rican amazon (Amazona vittata), also known as the Puerto Rican parrot, is a special type of parrot found only in Puerto Rico. People also call it cotorra puertorriqueña or iguaca. This parrot is part of a group called Amazona, which lives in the Americas.

These parrots are about 28 to 30 centimeters (11 to 12 inches) long. They are mostly green with a bright red forehead and white rings around their eyes. There used to be two types, or subspecies, of this parrot. One lived on Culebra Island but died out in 1912. Scientists are not sure if it was very different from the main type. The closest relatives of the Puerto Rican amazon are thought to be the Cuban amazon and the Hispaniolan amazon.

Puerto Rican amazons are ready to have babies when they are about three or four years old. They lay eggs once a year in holes inside trees. The mother parrot stays on the eggs until they hatch. Both parents feed the baby parrots, which leave the nest about 60 to 65 days after hatching. These parrots eat many different things from the tops of trees, like flowers, fruits, leaves, bark, and nectar.

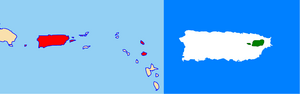

This parrot is the only native parrot left in Puerto Rico. Since 1994, it has been listed as critically endangered by the World Conservation Union. This means it is at a very high risk of dying out. Long ago, there were many Puerto Rican amazons all over the island. But in the 1800s and early 1900s, their numbers dropped a lot because their homes (forests) were destroyed. They disappeared completely from Vieques and Mona Island. In 1968, people started working hard to save these birds from disappearing forever.

Contents

Puerto Rican Amazon: History and Family Tree

The Puerto Rican amazon was first described by a French scientist named Georges-Louis Leclerc in 1780. Another scientist, Pieter Boddaert, gave it the scientific name Psittacus vittatus in 1783. The name vittatus is Latin for "banded," which describes the parrot's look.

Later, the parrot was placed in the Amazona group. In North America, it's also called the "Puerto Rican parrot." The native Taíno people of Puerto Rico called it the iguaca. This name sounds like the parrot's flight call.

There are two types of Puerto Rican amazons that scientists know about:

- A. v. vittata: This is the main type, and it's the only one still alive today. It lives in Puerto Rico and used to live on nearby Vieques Island and Mona Island.

- A. v. gracilipes: This type lived on Culebra Island but is now extinct. Scientists are not sure how different it was from the main type.

How the Puerto Rican Amazon Evolved

Scientists believe that birds in the Caribbean, like the Puerto Rican amazon, came from birds that flew over the ocean from Central, North, or South America. Parrots are strong flyers, which helped them travel across large areas of water.

All the Amazona parrots in the Greater Antilles (like Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola) look similar. They are mostly green and have white rings around their eyes. Studies suggest that the Puerto Rican amazon, the Cuban amazon, and the Hispaniolan amazon are very closely related.

What the Puerto Rican Amazon Looks Like

The Puerto Rican amazon is about 28 to 30 centimeters (11 to 12 inches) long and weighs around 250 to 300 grams (9 to 11 ounces). Even though it's small for an amazon parrot, it's similar in size to other parrots in the Greater Antilles.

Males and females look very similar. Both have mostly green feathers, but the edges of their feathers are blue. The main flight feathers on their wings are dark blue. When they fly, you can see bright blue feathers on the underside of their wings. Their tail feathers are yellow-green. Their bellies are lighter and yellowish. They have a red forehead and white circles around their eyes. Their eyes are brown, their beak is horn-colored, and their legs are yellow-tan.

The only way to tell males and females apart, besides DNA tests, is by how they act during the breeding season. Young parrots look like the adults.

Where the Puerto Rican Amazon Lives

Before Spanish settlers arrived, the Puerto Rican amazon was common all over Puerto Rico. Some evidence suggests they might have also lived on other islands like Antigua, Barbuda, and the Virgin Islands.

In the past 200 years, many things caused the parrot's numbers to drop. These include:

- Farming: Forests were cut down to make space for farms, especially for sugar, cotton, and rice.

- Roads and buildings: More land was used for human development.

- Taking chicks as pets: Young parrots were taken from their nests.

- Hunting: Farmers sometimes hunted the parrots because they ate their crops.

As forests disappeared, the parrots lost their homes and food sources. By the 1960s, they could only be found in the El Yunque National Forest in the Luquillo Mountains.

By the 1950s, there were only about 200 parrots left in the wild. In 1975, their numbers hit a very low point with only 13 birds. The population slowly grew, reaching about 47 birds by August 1989. However, Hurricane Hugo hit Puerto Rico in September 1989, and the parrot population dropped to only 23 birds.

In 2004, there were 30 to 35 parrots in the wild. Their numbers have been stable, but they still go up and down. Today, the area where they live is much smaller than it used to be.

Puerto Rican Amazon Behavior

The Puerto Rican amazon is active during the day, usually starting about half an hour after sunrise. They are good at hiding in their nests because their green feathers blend in with the trees. Outside the nest, they can be loud and noisy. When they fly, their colors stand out against the forest.

These parrots can fly moderately fast, up to about 30 kilometers per hour (19 mph). They are also very agile, meaning they can move quickly to avoid predators in the air. When looking for food, parrots often fly in pairs. Families, including parents and their young, tend to stay together. The amazon makes two main calls: a squawk when taking off and a loud "bugle" call used during flight, which can mean different things depending on the situation.

What the Puerto Rican Amazon Eats

Like most amazon parrots, the Puerto Rican amazon is a herbivore, meaning it eats plants. Its diet includes flowers, fruits, leaves, bark, and nectar from the tops of trees. They have been seen eating over 60 different types of plant materials.

They usually pick fruits one at a time with their foot. When they eat, they take their time, spending 8 to 60 seconds on each item.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Puerto Rican amazons usually mate for life. They only find a new partner if one parrot dies or leaves the nest. When a new pair forms, they do special mating dances, bowing and spreading their wings and tails.

These parrots nest in holes in tree trunks, either natural ones or those made by other animals. They prefer to nest in Palo colorado trees, but also use other trees like laurel sabino. These trees are old and strong, providing good protection for the nest. Recently, they have also started nesting in special wooden boxes made by people to help them. Nests are usually 7 to 15 meters (23 to 49 feet) above the ground. The male often looks for nest sites, but the female seems to make the final choice. They clean the nest but don't add any soft lining.

Puerto Rican amazons are ready to have babies at 4 years old in the wild, or 3 years old if they are in captivity. They usually have babies once a year, between January and July (the dry season). The female lays 2 to 4 eggs and sits on them for 24 to 28 days. The male stays near the nest and brings food to the female. The female only leaves the nest if she needs to scare away predators or if the male hasn't brought food for a long time.

Both parents feed the chicks until they leave the nest, which is usually 60 to 65 days after hatching. Even after leaving the nest, the young parrots stay with their parents until the next breeding season.

Puerto Rican amazons are social when doing daily activities, but they protect their nests. They usually defend an area of about 50 meters (164 feet) around their nest. They are very careful when leaving the nest to avoid attracting predators. They mostly use loud calls to defend their territory, but sometimes they will fight other parrots.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

On March 11, 1967, the Puerto Rican amazon was added to the U.S. list of endangered species. At that time, there were only about 70 parrots left. In 1968, efforts began to help the wild population grow. In 1972, when there were only 16 parrots left, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) started a program to breed parrots in captivity. This program has been very successful.

In 2006, 22 parrots were released into the Rio Abajo State Forest to start a new wild population. More parrots were released there later. By 2012, there were an estimated 58 to 80 parrots in the wild and over 300 in captivity.

The World Conservation Union (IUCN) has listed the Puerto Rican amazon as critically endangered since 1994. This means it's at a very high risk of dying out. International trade of these parrots or their parts is illegal.

Threats to the Puerto Rican Amazon

Human activities are the main reason for the parrot's population decline. While the early Taíno people hunted them, they did not harm the population much. Later, the destruction of their forest homes, capturing young birds for pets, hunting, and predators caused a sharp decline. Cutting down mature forests for farming is the biggest reason for the population drop.

Natural predators of the Puerto Rican amazon include the red-tailed hawk, the broad-winged hawk, the peregrine falcon, and the pearly-eyed thrasher. The pearly-eyed thrasher became a problem in 1973. To help, special deep nests were made for the parrots to prevent thrashers from competing for nest spots. Other animals like honeybees, black rats, and Indian mongooses can also compete for nesting holes. Rats and mongooses might also eat eggs and chicks.

Natural disasters like hurricanes were not a big threat when there were many parrots. But now, with fewer parrots and smaller living areas, hurricanes can cause a lot of damage. For example, Hurricane Hugo in 1989 reduced the population from 47 to 23 birds.

Recovery Plan for the Puerto Rican Amazon

To help the Puerto Rican amazon, a recovery plan was started in 1968. The main goal was to increase the population. This plan includes:

- Creating two separate wild populations, each with at least 500 birds.

- Protecting the places where these parrots live.

- Controlling predators and other animals that compete with the parrots.

A captive breeding program was started in 1973 at the Luquillo Aviary. Another one began in 1993 at the Rio Abajo State Forest. In 2007, new facilities were opened at the Iguaca Aviary in El Yunque National Forest.

In 2012, it was reported that small planes flying too close were bothering the parrots. A proposed gas pipeline project also worried conservationists because it would cut down more forests.

However, new conservation efforts have also begun. In 2011, scientists at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez studied the parrot's DNA. This project was funded by the community, with students organizing art shows and people making small donations. This research helps in breeding programs and tracking individual birds.

In August 2013, it was exciting news that parrots were nesting on their own in the Río Abajo State Forest. This showed that the released parrots were adapting well to the wild. Experts also found an unmonitored population of about 50 birds spread across Puerto Rico.

In November 2013, plans were announced to create a third population in the Maricao State Forest. The year 2013 was a record year for the breeding program, with 51 young parrots successfully leaving the nest. The wild population also grew by 15 chicks. By this time, there were around 500 Puerto Rican amazons in total.

In August 2015, a group of 25 parrots was moved to a new facility in Maricao. They will stay there for about a year to get used to the area before being released to start a new population. In early 2020, 30 more parrots were released into the El Yunque rainforest.

See also

In Spanish: Cotorra puertorriqueña para niños

In Spanish: Cotorra puertorriqueña para niños