American propaganda of the Spanish–American War facts for kids

The Spanish–American War (April–August 1898) was a big moment in history. It showed how powerful news and media could be. This war is often seen as the start of "yellow journalism", a type of news reporting that uses exciting or exaggerated stories to grab attention.

It was the first time that news reports played a huge role in starting a military conflict. The war began because the United States was interested in a fight for freedom in Cuba. Cuba was a colony of Spain. American newspapers made people very interested in the war. They did this by making up or greatly exaggerating terrible stories about what was happening in Cuba. This made many Americans feel that the U.S. should step in and help.

Many people in the United States wanted a war with Spain. They used different ways to get Americans to support their ideas. For example, William Randolph Hearst, who owned The New York Journal, was competing with Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World. Hearst saw the war as a way to sell more newspapers. Many newspapers printed very exciting stories. They sent reporters to Cuba to cover the war. These reporters often had to hide from Spanish officials. They usually couldn't get reliable news. So, they often relied on people who gave them information. Many stories came from second or third-hand accounts. Journalists often made these stories bigger, changed them, or completely made them up to make them sound more dramatic.

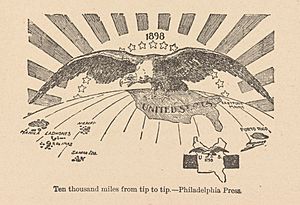

Theodore Roosevelt, who was a high-ranking official in the Navy at the time, also wanted the conflict. He hoped it would help heal the country after the American Civil War. He also wanted to make the U.S. Navy stronger. At the same time, he wanted the United States to become a more important country in the world. Roosevelt pushed the United States Congress to help the Cuban people. He said the Cubans were weak and needed America's help to justify military action.

Contents

Why the War Started

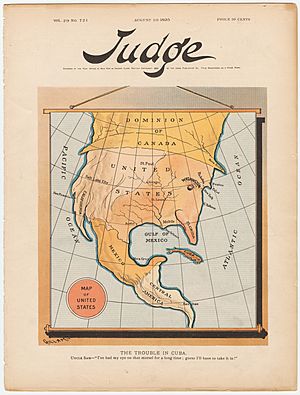

The United States had wanted to get Cuba from the Spanish Empire for a long time. Spain's power was fading. In 1848, President James K. Polk offered to buy Cuba for $100 million. But Spain said no.

Later, in 1854, the public found out about the Ostend Manifesto. This was a plan that said the U.S. could take Cuba by force if Spain refused to sell it. This idea made many people angry. They thought that taking more land was linked to expanding slavery. So, the idea of taking Cuba was stopped for a while.

The American Civil War (1860-1865) put a stop to these expansion plans. But after the Civil War ended, the idea of "Manifest Destiny" came back. Manifest Destiny was the belief that the United States was meant to expand its territory. In 1896, the Republican Party, which won the White House, used this idea to support expanding America's power overseas.

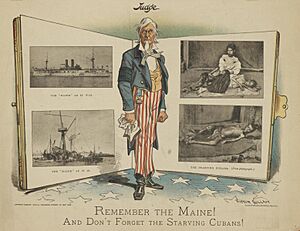

Before the Spanish-American War, things were very tense. Many people in the media, like William Randolph Hearst, and in the military wanted the U.S. to help the revolutionaries in Cuba. Most Americans were convinced, and they started to feel very angry towards Spain. American newspapers printed exciting stories. These stories showed terrible acts, some true and some made up, done by the Spanish. For example, thousands of Cubans were forced to move to camps in the countryside. Many stories talked about gruesome killings. In Havana, there was a riot by people who supported Spain. They destroyed the printing presses of newspapers that had criticized the Spanish Army.

News and Propaganda

Before the USS Maine sank, an American reporter in Cuba said that the American people were being fooled by the news. He said most stories came from third-hand information. This information was often given by Cuban interpreters and informants. These people usually supported the revolution. They would change the facts to make the revolution look good. Small fights would become big battles. Spanish rule was shown as cruel, with torture and widespread stealing by Spanish forces. Reporters rarely checked the facts. They just sent the stories to their editors in the U.S. There, the stories would be changed even more and printed.

This type of reporting became known as yellow journalism. Yellow journalism spread across the country. Its propaganda helped push the United States into military action. The U.S. sent troops to Cuba and other Spanish colonies around the world.

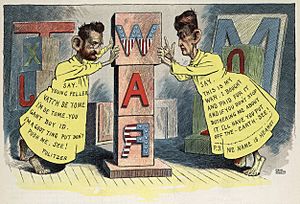

Hearst and Pulitzer's Rivalry

The two newspaper owners who created yellow journalism were William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. They were fighting to sell more newspapers in New York City. Pulitzer owned the New York World, and Hearst owned the New York Journal. These two men often ignored responsible journalism. They are widely believed to have helped lead the U.S. into the Spanish–American War.

Their stories made Americans believe that the Cuban people were being treated unfairly by the Spanish. They said the only way for Cubans to get their freedom was if America stepped in. Hearst and Pulitzer made their stories seem real by just saying they were true. They also gave false names, dates, and places for battles and terrible acts by the Spanish. Newspapers even claimed that the government could prove their facts.

While Hearst and Pulitzer had a lot of influence, especially among richer people and government officials, many newspapers in the Midwest disagreed with their sensational yellow journalism. Victor Lawson, who owned the Chicago Record and Chicago Daily News, focused on reporting only the facts. He had many middle-class readers. Lawson even set up an office in Key West to watch the Cuban conflict closely.

However, even the Midwest newspapers' focus on facts ended up helping cause the war. Since the events in Cuba were not always believable, many Midwest newspapers started writing about issues at home. They focused on how Cuba affected the American economy. American trade with Cuba was very important. By covering these issues, many readers in the Midwest began to believe that protecting these trade interests was necessary for a stable economy. The easiest way to protect these interests seemed to be war with Spain.

Hearst and Pulitzer worried that Lawson and other Midwest newspapers were hurting their goals. They looked for any story that could attract more middle-class readers. Two incidents helped them. The first was the Olivette Incident. A young Cuban woman named Clemencia Arango was taken by Spanish officials from a ship going to New York. They thought she was carrying letters to rebel leaders. She was searched in a private room. A reporter for Hearst, Richard Harding Davis, wrote about it. The headlines were shocking: "Does our flag shield women?" and "Refined Young Women Stripped and Searched by Brutal Spaniards While Under Our Flag on the Ollivette." Hearst even got support from American women at first. But he got into trouble when Arango said the stories were not quite true. Hearst never apologized, but he had to print a letter explaining that his article did not mean male police searched the women. He said a female police officer did the search properly, with no men present.

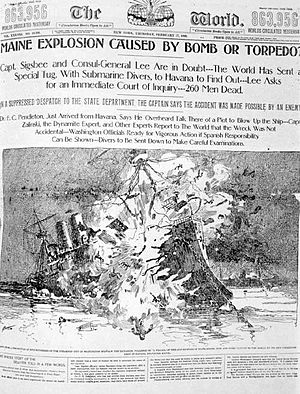

Luckily for Hearst, another incident happened soon after. It involved a Cuban dentist named Ricardo Ruiz. He had moved to the U.S. during an earlier Cuban war and became a U.S. citizen. Ruiz later returned to Cuba, got married, and had children. He was put in prison because he was suspected of helping rebels. He died in prison. The next day, Hearst's newspaper had a headline that read: "American Slain in Spanish Jail." Ruiz's story greatly increased tension between the U.S. and Spain, especially among middle-class Americans who felt a connection to him. Even though these events made Americans more angry at Spain, they were not enough to start a war directly. It would be the exaggerated stories about the sinking of the USS Maine that finally led to war.

The Sinking of USS Maine

Frederic Remington, an artist hired by Hearst to draw pictures for articles about the Cuban Revolution, got bored. Cuba seemed peaceful. In January 1897, he sent a message to Hearst: "Everything is quiet. There is no trouble. There will be no war. I wish to return." Hearst's famous reply was: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

After the USS Maine sank, Hearst quickly printed a story with the headline: "The War Ship Maine was Split in Two by an Enemy's Secret Infernal Machine." The story claimed that Spain had placed a torpedo under the USS Maine and set it off from shore. Hearst then printed another article with drawings of Spain's secret torpedoes. Captain Sigsbee of the USS Maine sent a telegram to the Secretary of the Navy. He said people should wait for more reports before making judgments. At the Navy's investigation, Sigsbee still believed a mine caused his ship to sink. The investigation agreed, but they couldn't find proof to blame "any person or persons."

Later, in 1974, a different investigation found the opposite. It said the explosion probably started inside the ship.

Many newspapers, like Hearst's, printed stories across the country blaming the Spanish military for the USS Maine's destruction. These stories deeply affected Americans. Public opinion became very divided. One large group wanted to attack Spain right away. Another group wanted to wait for more proof. Those who wanted to attack wanted to remove Spain from power in its colonies near the U.S. The people who were easily convinced by yellow journalism eventually won. American troops were sent to Cuba.

See also

In Spanish: Propaganda en la Guerra hispano-estadounidense para niños

In Spanish: Propaganda en la Guerra hispano-estadounidense para niños