April Uprising of 1876 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids April Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Great Eastern Crisis | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| around 10,000 men | around 100,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 15,000–30,000 killed (including civilians) | 200–4,000 killed | ||||||

The April Uprising (Bulgarian: Априлско въстание, romanized: Aprilsko vastanie) was a big rebellion organized by Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire. It happened from April to May in 1876. The Ottoman Empire was a large empire that ruled over many different peoples, including Bulgarians, for a long time.

The rebellion was stopped by Ottoman forces. These included regular soldiers and also irregular groups called bashi-bazouks. These groups were known for being very harsh. They caused a lot of harm to both rebels and people who were not fighting. One terrible event was the Batak massacre.

News of these events, called the Bulgarian Horrors by the press, spread quickly. Americans like journalist Januarius MacGahan and diplomat Eugene Schuyler helped share the stories. Their reports made many people in Europe very upset. This public anger led to calls for changes in how the Ottoman Empire ruled the Bulgarian lands.

This shift in public opinion was very important. Even Britain, which was usually a close friend of the Ottoman Empire, started to demand action. This eventually helped lead to the creation of a separate Bulgarian state in 1878.

Contents

Why Did the Uprising Happen?

Life in Ottoman Bulgaria

For centuries, Bulgarians lived under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. In the 18th and 19th centuries, new ideas about nations and self-rule became popular in Europe. People started to believe that groups with a shared culture and language should have their own country.

Bulgarians felt they were treated unfairly by the Ottoman rulers. They had fewer rights than Muslims and faced social and political challenges.

Growing Problems for the Ottoman Empire

In the mid-1870s, the Ottoman Empire faced many problems. It was struggling financially and raised taxes, especially on non-Muslims. This made tensions between Muslims and Christians even worse.

There were also other rebellions, like the one in Herzegovina. The Ottoman Empire struggled to put down these revolts. The harsh ways they dealt with rebels made the empire look bad to other countries. These problems encouraged Bulgarian leaders to plan their own uprising.

Planning the Rebellion

In November 1875, a group called the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee met in Romania. They decided that the time was right for a big rebellion. They planned for it to happen in April or May 1876.

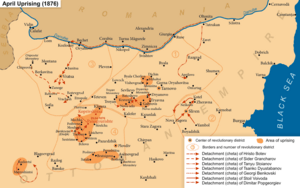

They divided Bulgaria into five areas for the uprising. Each area had its own leader. For example, Georgi Benkovski was a key leader in the Plovdiv district, which later moved its center to Panagyurishte.

The rebels secretly gathered weapons and supplies. They even made a simple cannon out of cherry wood!

A meeting of rebel leaders was held on April 14, 1876, near Panagyurishte. They discussed when to start the uprising. However, someone told the Ottoman authorities about the plan. Because of this, the Ottoman police tried to arrest a local leader, Todor Kableshkov, on April 20.

The rebel committee had also discussed how to act during the uprising. They planned to protect Muslims who did not fight against them.

The Uprising Begins and Is Stopped

First Actions

Because of the attempted arrests, the rebels in Koprivshtitsa had to start the uprising earlier than planned. On April 20, 1876, they attacked the Ottoman police headquarters. They killed some officers and forced the release of arrested rebels.

Within days, the rebellion spread across the Sredna Gora mountains and to some villages in the Rhodopes. Other areas also revolted, but on a smaller scale. Places like Gabrovo and Tryavna also saw fighting.

Ottoman Response

The Ottoman Empire reacted very quickly and harshly. They sent in irregular bashi-bazouks and army units. These forces attacked rebel towns starting on April 25.

They killed many civilians in towns like Panagyurishte, Perushtitza, Klisura, and Batak. The uprising was completely stopped by mid-May.

One of the last acts of resistance was by the poet Hristo Botev. He tried to help the rebels with a group of Bulgarians living in Romania. But his group was defeated, and Botev was killed.

The Ottoman government chose to use these irregular forces instead of just regular army units. This decision led to many more deaths. For example, the village of Bratsigovo fought a regular army unit and had fewer civilian deaths. But towns like Perushtitza, Panagyurishte, and Batak, which faced bashi-bazouk forces, suffered huge numbers of casualties.

Many historians agree that the uprising was not well-prepared. Some believe the organizers mainly wanted to draw attention from Europe and Russia to the difficult situation of Bulgarians under Ottoman rule.

How Many People Died?

An American diplomat named Eugene Schuyler wrote a detailed report about the uprising. He visited many towns and villages. He reported that 65 villages were burned, 5 monasteries were destroyed, and at least 15,000 people were killed. This included both rebels and people who were not fighting.

Schuyler especially highlighted the extreme and unnecessary violence used, particularly in Batak. Another British investigator, Walter Baring, largely confirmed Schuyler's findings. He estimated the number of victims to be around 12,000.

Other reports from French and Russian officials estimated the number of Bulgarian deaths to be between 25,000 and 40,000.

Reports also showed that very few peaceful Muslims were killed during the uprising. Schuyler reported about 115 Muslim casualties.

What Happened Next?

European Outcry and the Constantinople Conference

The April Uprising itself was not successful. But the brutal way it was stopped by the Ottomans caused a huge wave of anger across Europe. Even in Britain, public opinion changed. People demanded that the Ottoman Empire change how it governed.

Because of this, the major European powers held a meeting called the Constantinople Conference in December 1876. They suggested creating two self-governing Bulgarian regions. This proposal aimed to give Bulgarians more control over their own lives.

This was a big step for Bulgarians who had been fighting for freedom for decades. They had worked hard through their church leaders and educated people to gain more rights. The blood shed by the rebels also played a part in changing European minds.

The Ottoman Rejection and War

However, on January 20, 1877, the Ottoman government officially rejected the idea of Bulgarian self-governance.

This rejection gave Russia a reason to declare war on the Ottoman Empire. Russia had its own plans for the region. Less than two years after the uprising, Bulgaria, or at least a part of it, finally gained its freedom.

See Also

- Ottoman Bulgaria

- Razlovtsi insurrection

- Liberation of Bulgaria

- Kresna–Razlog uprising

- Bulgarian unification

- Edwin Pears

- Boyadzhik massacre