Hristo Botev facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Христо Ботев

Hristo Botev |

|

|---|---|

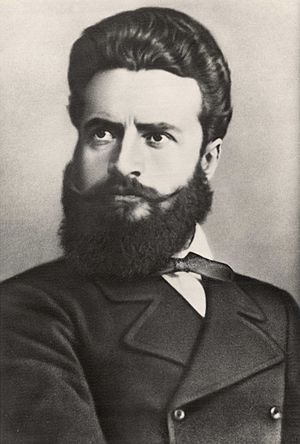

Botev c. 1875

|

|

| Born | Hristo Botyov Petkov 6 January 1848 Kalofer, Ottoman Bulgaria |

| Died | 1 June 1876 (aged 28) near Vola Peak, Vratsa Mountains (part of the western Balkan mountain range), Ottoman Bulgaria |

| Occupation | poet, journalist, revolutionary |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

| Spouse | Veneta Boteva |

| Children | Ivanka |

Hristo Botev (Bulgarian: Христо Ботев, pronounced [ˈhristo ˈbɔtɛf]), born Hristo Botyov Petkov, was a brave Bulgarian revolutionary and a talented poet. Many Bulgarians see Botev as a national hero and an important historical figure. His poems are great examples of the writing from the Bulgarian National Revival. This was a time when Bulgarians worked to regain their freedom. Botev was also ahead of his time with his ideas about politics and life.

Contents

Who Was Hristo Botev?

His Early Life

Hristo Botev was born in Kalofer, a town in what was then Ottoman-ruled Bulgaria. His father, Botyo Petkov, was a teacher. He was a very important person during the last part of the Bulgarian National Revival. His father taught Hristo many things and had a big impact on him.

In 1863, after finishing school in Kalofer, Botev went to a high school in Odessa. He was very impressed by the ideas of liberal Russian poets there. In 1865, he left high school. For the next two years, he worked as a teacher in Odessa and Bessarabia. During this time, he started writing his first poems. He also made strong connections with Russian and Polish revolutionary groups. His political ideas began to form.

Botev returned to Kalofer in early 1867. He temporarily took over his sick father's teaching job. In May, during a celebration for Saints Cyril and Methodius, he gave a public speech. He spoke against the Ottoman rulers and wealthy Bulgarians who he felt were helping the Ottomans. Because of this speech, Botev had to leave Kalofer. He first planned to go back to Russia. But he didn't have enough money. So, he went to Romania, where many Bulgarian exiles found safety.

Becoming a Revolutionary

For a while, Botev lived in an old mill near Bucharest. He lived with Vasil Levski, who later became a leader of the Bulgarian uprising. They became good friends. Botev later wrote about this time in his works.

From 1869 to 1871, Botev taught again in Bessarabia. He stayed close to the Bulgarian revolutionary movement and its leaders. In June 1871, he became the editor of a newspaper called "Word of the Bulgarian Emigrants." Here, he started publishing his early poems. He was put in prison for a few months because he worked with Russian revolutionaries. After that, Botev began working for the "Liberty" newspaper. This paper was edited by Lyuben Karavelov, another important Bulgarian writer and revolutionary. In 1873, Botev also edited a funny newspaper called "Alarm clock." In it, he wrote articles making fun of rich Bulgarians who didn't join the revolutionary movement.

The Bulgarian revolutionary movement faced a big problem. Vasil Levski, its main leader, was captured by Ottoman authorities in late 1872. Levski had created a network of secret revolutionary groups. These groups were overseen by the Bulgarian Central Revolutionary Committee (BCRC) in Romania. Their goal was to prepare Bulgarians for a future uprising against Ottoman rule. Levski was put on trial, sentenced to death, and hanged on February 19, 1873. His death was a huge blow to the revolutionaries.

After Levski's death, the BCRC split into two groups. Botev and his friends, including Stefan Stambolov, wanted to start an uprising right away. They believed it was the right time because of tensions between the Ottoman Empire, Serbia, and Russia. They also thought Levski's revolutionary network was still strong. Other revolutionaries, led by Lyuben Karavelov, felt it was too early for such actions. The revolt in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1875 made Botev and Stambolov even more sure. They thought a rebellion should start in Bulgaria too. They believed more trouble in the Balkans would get the attention of powerful European countries. In August 1875, Karavelov, who was sick, stepped down as BCRC president. Botev was chosen as the new president. He believed Bulgarians were always ready to fight. He thought careful preparations were not needed. This led to the unsuccessful Stara Zagora Uprising in September 1875.

His Last Fight

In early 1876, Bulgarian revolutionaries living in Romania were sure an armed uprising against Ottoman rule was coming. In April 1876, a group in Bechet decided to form an armed company. They planned to cross the Danube River and join the uprising. Leaders of the planned uprising in the Vratsa area came to Romania. They met Botev and convinced him that his company would be best used in their region. As fighters were gathered and armed, news arrived that the uprising had started too early.

The organizers tried to find an experienced Bulgarian guerrilla leader to command the company. But two leaders they asked refused for political reasons. So, Botev himself took command, even though he didn't have much combat experience. Nikola Voinovski, a trained military officer, provided the military knowledge. Because they were in a hurry and needed to be secret, the company didn't get formal combat training. They had to rely on each person's fighting skills. The news of the uprising made them move faster. On May 16, 1876, the 205-person company was ready to go.

Botev came up with a clever plan to cross into Ottoman land without immediately alerting anyone. The rebels pretended to be gardeners. They boarded the Austro-Hungarian passenger steamship Radetzky in groups at several Romanian ports. When the last group boarded, the rebels took out their hidden weapons and took control of the ship. (This event is remembered in a famous poem and song.) Botev spoke to the captain, Dagobert Engländer. He told him they intended to reach the Ottoman side of the Danube. He explained why they were doing this. Captain Engländer was so touched by Botev's speech that he fully supported them. He even refused to help the Ottoman authorities when they asked to use his ship to chase the rebels.

Botev and his men got off the ship near Kozloduy. They all kissed the soil of their homeland. As they moved inland, they slowly realized that the uprising in the Vratsa area had not happened. Also, because other uprisings had been violently stopped, the entire Ottoman army was ready. Regular soldiers and irregular bashi-bazouks were patrolling the area. Botev and his officers decided to head for the safer Vratsa Mountains. They tried to encourage the Bulgarian people along the way to join them. But the people were scared by the huge Ottoman military presence and did not openly rebel.

The company was almost immediately attacked by bashi-bazouks. Voinovski showed excellent defensive skills. The company's morale was still high. On May 18, many bashi-bazouks caught up with the company. Botev had to take a stand on Milin Kamak Hill, about 50 km from the Danube. Under Voinovski's command, the rebels held off the much larger Ottoman irregular forces. They didn't suffer many casualties until two Ottoman companies of regular soldiers arrived. These regular soldiers used two small cannons and better rifles. They caused many casualties among the rebels from a safe distance. But their three attempts to charge forward were stopped by the rebels' disciplined firing. The Ottoman company lost about 30 killed or wounded. As was their custom, the Ottomans stopped fighting at nightfall. The rebels split into two groups and managed to sneak through enemy lines. They continued their march towards the mountains.

The next day, they didn't see the enemy. But it was clear that no local help would come. On the morning of May 20, guards saw advancing bashi-bazouks and five companies of regular Ottoman troops. The men quickly took strong positions near Mount Okoltchitza. The defense was split into two parts. Voinovski commanded one, and Botev commanded the other. Soon, two battalions of Ottoman regulars attacked Voinovski's fighters. The bashi-bazouks focused on Botev's position. Voinovski's men fired together, causing heavy losses to the enemy. They also stopped attempts to surround them. Botev's men also pushed back several bashi-bazouk attacks with a counterattack.

At dusk, the fighting stopped as the Ottomans again pulled back for the night. The rebels lost about 10 killed, and many more were wounded that day. It was at this moment, at dusk on May 20, 1876 (which is June 1, 1876, on the modern calendar), that a single bullet hit Botev in the chest. He died instantly. This bullet was most likely fired by a hidden Ottoman sharpshooter. After their leader died, the company's morale dropped. They began to scatter. Very few managed to escape capture or death. In total, 130 company members were killed. Most of the others were captured, imprisoned, or executed.

Botev left behind his wife, Veneta, his daughter, Ivanka, and his stepson, Dimitar.

A National Hero

After Bulgaria became free, smart people and writers like Zahari Stoyanov and Ivan Vazov carefully built up Botev's image. They wanted him to be seen as a revolutionary hero. They didn't focus on some of his more debated ideas, like his early views on anarchy or socialism. This was so they wouldn't upset the middle-class people. Later, his connection to Russian anarchists helped the Communist government in the 20th century. They presented him as a pioneer of Bulgarian socialism, which kept his heroic status alive. Because he is such a famous public figure, Botev has sometimes been the subject of sensational stories in the news.

His Literary Works

In 1875, Botev published his poems in a book called "Songs and Poems." He did this with his friend, the revolutionary poet and future politician, Stefan Stambolov. Botev's poems showed the feelings of poor people. They were full of revolutionary ideas. They fought for freedom against both foreign rulers and local oppressors. His poetry was inspired by Russian revolutionary thinkers and the ideas of the Paris Commune. Because of this, Botev grew as both a poet and a revolutionary. Many of his poems are full of revolutionary passion and determination. These include My Prayer, At Farewell, Hajduks, In the Tavern, and Struggle. Others are romantic, like a ballad (Hadzhi Dimitar), or sad. Perhaps his greatest poem is The Hanging of Vasil Levski.

Poems:

| Original Title | Transliteration | Translation | First Published |

|---|---|---|---|

| Майце си | Maytse si | To My Mother | 1867 |

| Към брата си | Kam brata si | To My Brother | 1868 |

| Елегия | Elegiya | Elegy | 1870 |

| Делба | Delba | Division | 1870 |

| До моето първо либе | Do moeto parvo libe | To My First Love | 1871 |

| На прощаване в 1868 г. | Na proshtavane v 1868 g. | At Farewell in 1868 | 1871 |

| Хайдути | Hayduti | Hajduks | 1871 |

| Пристанала | Pristanala | Eloped | 1871 |

| Борба | Borba | Struggle | 1871 |

| Странник | Strannik | Stranger | 1872 |

| Гергьовден | Gergyovden | St. George's Day | 1873 |

| Патриот | Patriot | Patriot | 1873 |

| Защо не съм...? | Zashto ne sam...? | Why am I not...? | 1873 |

| Послание (на св. Търновски) | Poslanie (na sv. Tarnovski) | Epistle (to the Bishop of Tarnovo) | 1873 |

| Хаджи Димитър | Hadji Dimitar | 1873 | |

| В механата | V mehanata | In the Tavern | 1873 |

| Моята молитва | Moyata molitva | My Prayer | 1873 |

| Зададе се облак темен | Zadade se oblak temen | A Dark Cloud Is Coming | 1873 |

| Ней | Ney | To Her | 1875 |

| Обесването на Васил Левски | Obesvaneto na Vasil Levski | The Hanging of Vasil Levski | 1876 |

His Legacy

In 1885, a group was formed to remember Botev. This happened on the anniversary of his death, May 20 / June 1. A monument was built in the main square of Vratsa in 1890. King Ferdinand was there for the opening. Important Bulgarians like Stefan Stambolov and Zahari Stoyanov wrote a lot about Botev and his actions for Bulgaria. Soon, Botev became a legendary figure in the Bulgarian National Revival. Even today, he is remembered as one of Bulgaria's two greatest revolutionaries, along with Vasil Levski.

A copy of the Danube steamship Radetzky, which Botev used, was rebuilt. Over 1 million students raised money for it in 1966. It is now a museum ship.

Every year on June 2, at exactly 12:00 PM, air raid sirens sound across Bulgaria for one minute. This honors Hristo Botev and all those who died for Bulgaria's freedom. People stand still for 2 to 3 minutes until the sirens stop. (Even though Botev died on June 1, 1876, on the modern calendar, his death is remembered on June 2. This tradition started when Bulgaria adopted the modern calendar in 1916.)

Many things are named after Hristo Botev:

- Botev Point and Botev Peak on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands

- The highest peak in Stara planina

- The city of Botevgrad

- Streets and boulevards in most Bulgarian cities

- Streets in some North Macedonian cities

- Streets and boulevards in many Romanian cities

- A number of schools and high schools

- Several football clubs – Botev Plovdiv, Botev Vratsa, Botev Galabovo and many more.

- Several football stadiums in Bulgaria

- Hristo Botev Radio - the second channel of Bulgarian National Radio

- The International Botev Prize

- Asteroid (225238) 2009 QJ5, discovered on August 23, 2009, by F. Fratev – Zvezdno Obshtestvo Observatory (Bulgaria).

- An avenue in Kraków, Poland

- A street in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (renamed in 1995)

- A street in Chișinău, Republic of Moldova

- A street (Botevova) in Prague, Czech Republic (in a housing estate where all the streets are named after Bulgarian places and people)

See also

In Spanish: Hristo Botev para niños

In Spanish: Hristo Botev para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |