Archibald Hill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Archibald Vivian Hill

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 26 September 1886 Bristol, England

|

| Died | 3 June 1977 (aged 90) Cambridge, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Mechanical work in muscles Muscle contraction model Founding biophysics Hill equation (biochemistry) |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Neville Keynes |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1922) Royal Medal (1926) Actonian Prize (1928) Copley Medal (1948) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiology and biophysics |

| Institutions | Cambridge University University of Manchester University College, London |

| Academic advisors | Walter Morley Fletcher |

| Notable students | Te-Pei Feng Ralph H. Fowler Bernard Katz |

| Notes | |

|

He is notably the father of Polly Hill, David Keynes Hill, Maurice Hill, and the grandfather of Nicholas Humphrey.

|

|

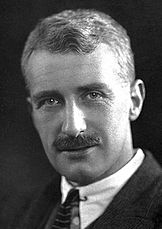

Archibald Vivian Hill CH OBE FRS (born September 26, 1886 – died June 3, 1977), often called A. V. Hill, was a famous British scientist. He was a physiologist, which means he studied how living things work. He also helped start new fields like biophysics (the physics of living things) and operations research (using science to make better decisions). In 1922, he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He shared this award for his important discoveries about how muscles produce heat and do work.

Contents

A Life of Science and Service

Early Life and Learning

Archibald Vivian Hill was born in Bristol, England. He went to Blundell's School and then to Trinity College, Cambridge. He was a brilliant student, especially in math. He was even called a "wrangler," which means he was one of the very best math students in his year.

While still at university, in 1909, he came up with an important idea. This idea helped explain how certain chemicals, like nicotine, attach to parts of cells called "receptors." This was a big step in understanding how nerves and muscles communicate.

Helping Out in World War I

When World War I started in 1914, Hill joined the army as a musketry officer. He was a very good shot! At first, scientists were not used much in the war effort.

But in 1915, Hill was asked to help with anti-aircraft guns. He quickly came up with a simple way to measure how high enemy planes were flying. He then realized he could use mirrors to see where smoke shells exploded. By using math, he could figure out how to aim the anti-aircraft guns better.

Hill put together a special team to help him. They were called "Hill's Brigands." This group included older men, injured soldiers, and young lads too young for regular service. They also worked on finding enemy planes by listening to their sounds. Hill was very dedicated, speeding between their work sites on his motorcycle. For his efforts, he received an award called the Order of the British Empire.

A Nobel Prize for Muscle Science

After the war, Hill became a professor at University College London. He spent many years studying muscles. He made very careful measurements of the heat muscles produce when they contract (tighten) and relax. He found that muscles produce heat when they work, using up energy. But they don't produce heat when they relax, which is a passive process.

Hill even used himself for experiments! He would run every morning to study how his body used energy. He discovered that our bodies use stored energy during a quick sprint. Afterwards, we breathe more to "pay back" this "oxygen debt."

His work helped explain how muscles create movement. For these amazing discoveries about muscle function, he shared the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He is seen as one of the people who started the field of biophysics.

Helping Scientists and the War Effort

In 1933, Hill helped start a group called the Academic Assistance Council. This group helped scientists who were being treated unfairly, especially those escaping from Nazi Germany. By the start of World War II, this group had saved 900 academics. Many of them later won Nobel Prizes themselves! Hill even had a toy figure of Adolf Hitler in his lab. He said it was to thank Hitler for sending so many great scientists to work with him. Hill believed that "Laughter is the best detergent for nonsense."

During World War II, Hill continued to help. He worked on the committee that led to the invention of radar, which was very important for detecting planes. He also worked to free refugee scientists who had been put in camps. From 1940 to 1945, he was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Cambridge University. An MP is a person elected to represent people in the government.

In 1940, he went to the British Embassy in Washington, D.C., to share war research with the United States. He convinced Britain to share almost all their secrets with the Americans (except for the atomic bomb). This sharing of scientific knowledge was a huge success for the Allies in the war.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Hill rebuilt his laboratory and continued his research. In 1951, a new Biophysics Department was created under his leadership.

He also led important scientific organizations, like the British Science Association and the International Council of Scientific Unions. He retired in 1967 and passed away in 1977. He was loved and respected by many scientists around the world who had been inspired by his work.

The Hill Equation: How Things Bind

Even though his muscle work won him the Nobel Prize, Hill is also famous for something called the Hill equation. He used this equation to understand how oxygen attaches to haemoglobin in our blood.

Simply put, the Hill equation helps scientists understand how strongly and how many molecules (like oxygen) attach to a protein (like haemoglobin). It shows if these molecules help each other bind (called "positive cooperativity") or if they don't (no cooperativity or "negative cooperativity"). This equation is very useful in biochemistry.

Family Life

In 1913, Archibald Hill married Margaret Neville Keynes. She was the daughter of a famous economist. Margaret was also the sister of two other well-known people: the economist John Maynard Keynes and the surgeon Geoffrey Keynes.

Archibald and Margaret had four children:

- Polly Hill (1914–2005), who became an economist.

- David Keynes Hill (1915–2002), who became a physiologist, just like his father.

- Maurice Hill (1919–1966), who became an oceanographer.

- Janet Hill (1918–2000), who became a child psychiatrist.

Awards and Recognition

Archibald V. Hill received many honors for his important work:

- Officer of the Order of the British Empire (1918)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1918)

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1922)

- He gave the famous Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in 1926, teaching about "Nerves and Muscles: How We Feel and Move."

- Associate Fellow in the National Academy of Kinesiology (1938)

- Order of the Companions of Honour (1946)

- Copley Medal from the Royal Society (1948)

- President of the British Science Association (1952)

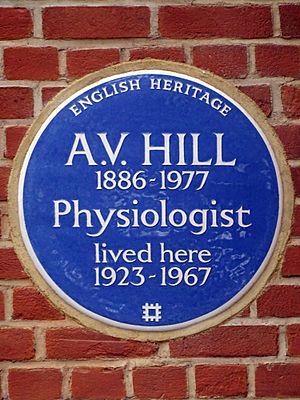

A Special Plaque

On September 9, 2015, a special "Blue Plaque" was put up at Hill's old home in Highgate, London. He lived there from 1923 to 1967. These plaques are put on buildings to honor famous people who lived or worked there.

His grandson, Nicholas Humphrey, shared that many famous people visited Hill's home. These included 18 Nobel Prize winners who had been exiled from their home countries, his brother-in-law John Maynard Keynes, and friends like Stephen Hawking and Sigmund Freud. After dinner, they would often have lively discussions about science or politics. His grandson also remembered Hill creating fun games for them, like frog racing in the garden!

Sir Ralph Kohn, who suggested the plaque, said that A. V. Hill greatly helped us understand how muscles work. His discoveries are still used in sports medicine today. He was also a great humanitarian and politician who strongly spoke out against the Nazi government for hurting scientists. Hill played a key role in helping many refugees find safety and continue their work in Britain.

See also

In Spanish: Archibald Vivian Hill para niños

In Spanish: Archibald Vivian Hill para niños