Badger culling in the United Kingdom facts for kids

Badger culling in the United Kingdom is when badgers are killed in certain areas and at specific times. This is allowed under special permits. The main goal is to reduce the number of badgers. People hope this will help control the spread of a disease called bovine tuberculosis (bTB).

Humans can get bTB, but it's not a big risk to our health. This is because milk is pasteurised (heated to kill germs). Also, there's a vaccine called BCG vaccine. The disease mostly affects farm animals like cows, pigs, and goats. It also affects some wild animals, like badgers and deer. In the 2010s, bTB spread a lot in western and southwestern England and Wales. Some people think this happened because badgers were not controlled.

In 2013, badger culling was tried in two areas in England. These trials were controversial. The main goal was to see if shooting badgers freely was humane. Before, badgers were trapped in cages first. The trials continued in 2014 and 2015. They expanded to bigger areas in 2016 and 2017. In 2020, there were plans to kill about 60,000 badgers in new areas.

Contents

- Why are badgers protected?

- Why do some people support culling?

- Why do some people oppose culling?

- What are the alternatives to culling?

- History of culling

Why are badgers protected?

European badgers (Meles meles) are not an endangered species. But they are among the most protected wild animals in the UK. Laws like the Protection of Badgers Act 1992 keep them safe. Other laws also protect them.

Why do some people support culling?

Before 2012, the government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) said badger control was needed. They wanted to keep animals healthy. They also wanted to support farms that produce beef and dairy. This helps meet trade rules and lowers costs for farmers and taxpayers.

Understanding bovine TB

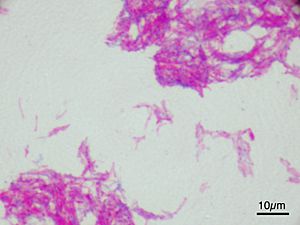

The Mycobacterium bovis bacterium causes bovine TB (bTB). Humans can get infected by this germ. Between 1994 and 2011, there were 570 human cases of bTB. Most of these were in older people. They might have been infected before milk was commonly pasteurised.

One way humans can get bTB is by drinking infected, unpasteurised milk. Pasteurisation kills the bacterium. Badgers can get bTB and pass it to cows. This can then affect the human food chain. Culling badgers is a way to reduce their numbers. This aims to lower the spread of bTB to humans.

Once an animal has bTB, it can spread in a badger's home, called a sett. This happens through breathing or waste. Badgers travel far at night. This means they can spread bTB over long distances. They also mark their territory with urine. This urine can have many bTB bacteria. The RSPCA says that about 4–6% of badgers are infected.

In 2014, bTB was mostly in southwest England. It might have reappeared after the 2001 United Kingdom foot-and-mouth outbreak. This outbreak led to many cows being killed. Farmers then bought new animals. Some of these new animals might have had bTB without anyone knowing.

What are the costs of bTB?

The government has paid a lot of money to farmers. This was for outbreaks like foot and mouth disease in 2001. In that outbreak, £1.4 billion was paid in compensation.

Some farmer groups and Defra support badger culling. They say bTB costs farmers a lot. If a cow tests positive for bTB, it must be killed. The farmer gets paid for this. These groups also feel that other ways to control bTB are too expensive.

In 2005, trying to get rid of bTB in the UK cost £90 million. In 2009/10, it cost taxpayers £63 million in England. Another £8.9 million was spent on research. In 2010/11, nearly 25,000 cows were killed in England alone. The cost to taxpayers was £91 million. Most of this was for testing cows and paying farmers. Defra said in 2011 that bTB was not getting better. They thought it would cost over £1 billion in England over the next ten years.

Costs for individual farms

Farmers also face big costs. They lose money when animals cannot be moved. They have to buy new animals. They also pay for bTB testing. The average cost of a bTB outbreak on a farm is about £30,000. The government pays about £20,000 of this. Farmers have to pay about £10,000 for lost earnings and testing.

Why do some people oppose culling?

The risk of humans getting bTB from milk is very low. This is true if milk is pasteurised. Scientists say badger culling is not needed. Defra agrees that the risk to public health is low. They say this is thanks to milk pasteurisation and cow control programs.

Animal welfare groups like the Badger Trust and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) are against culling. They see it as random killing of badgers. Badgers have special legal protection in the UK. These groups say culling has only a small effect on bTB.

Cows and badgers are not the only animals that carry bTB. The disease can infect pets like cats and dogs. It can also infect wild animals like deer. Farm animals like horses and goats can also get it. In some parts of England, deer, especially fallow deer, might spread bTB. This is because they live in groups. Some say deer might spread bTB more than badgers in certain areas. In 2014, two people got bTB from contact with a domestic cat. These were the first known cases of cat-to-human bTB spread.

Research in 2016 showed that bTB might not spread directly between badgers and cows. Instead, it might spread through contaminated fields and dung. This means how farms handle waste is important. Researchers tracked cows and badgers. They found badgers rarely came close to cows. Experts said expanding the cull goes against science. They called it a "monstrous" waste of time and money.

What are the alternatives to culling?

The Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats says badger culling is only allowed if there are no other good options. Many people support alternatives to culling. In 2012, many Members of Parliament (MPs) voted to stop the badger cull. A petition against the cull got over 300,000 signatures. This was a record for a government e-petition.

Vaccination

In 2008, Hilary Benn, a government minister, talked about other actions. He said £20 million would be spent. This money was for making a good vaccine for cows and badgers.

In 2010, Defra approved a vaccine for badgers called Badger BCG. This vaccine only works on badgers that don't already have bTB. It must be given by injection. It can only be used by trained people. Defra funded vaccination programs. Other groups like the National Trust also funded smaller programs.

Given the current uncertainty about the ability of badger vaccination to reduce TB in cattle, the high cost of deploying it and its estimated effect on the number of TB-infected badgers and thus the weight of TB infection in badgers when compared to culling ... we have concluded that vaccination on its own is not a sufficient response

However, the government sees badger vaccination as part of a bigger plan. They say vaccination costs about £2,250 per square kilometre each year. Most farmers are not interested in paying this themselves.

In Wales, badgers are vaccinated instead of culled. In Northern Ireland, neither culling nor vaccination is done yet. But they are looking into it. Scotland was declared free of tuberculosis in 2009. So, there are no plans to cull badgers there.

Vaccinating cows could also help. It might reduce bTB in cows. But there are three problems:

- No vaccine guarantees full protection.

- Cows likely need re-vaccination every year.

- The BCG vaccine can make cows test positive for bTB even if they don't have it. This is called a "false positive." Scientists are working on a test to tell the difference. This is important for international trade.

As of 2011, Defra spent about £18 million on cow vaccines and tests. Good farm practices can also help. This includes feeding cows well. It also means buying healthy new animals. Keeping sheds clean and well-ventilated is also important.

History of culling

Early years (before 1992)

Many badgers in Europe were gassed in the 1960s and 1970s. This was to control rabies. The germ that causes bTB was found in 1882. But compulsory tests for the disease only started in 1960. A program of testing and killing infected cows began and worked well.

By 1960, people thought bTB might be gone from the UK. But in 1971, infected badgers were found in Gloucestershire. Tests showed badgers could spread bTB to cows. Some farmers tried to kill badgers on their land. Wildlife groups asked Parliament for help. Parliament passed the Badgers Act 1973. This made it illegal to kill badgers or disturb their homes without a permit. These laws are now in the Protection of Badgers Act 1992.

Randomised Badger Culling Trials (1998–2008)

In 1997, a scientific group published the Krebs Report. It said there was not enough proof that culling badgers would help control bTB. It suggested doing trials.

The government then started the Randomised Badger Culling Trials (RBCT). These trials happened from 1998 to 2005. About 11,000 badgers were trapped in cages and killed. The trials looked at bTB in areas with culling and areas without.

In 2003, some culling was stopped. This was because the trials showed more bTB outbreaks in areas where badgers were killed. This was compared to areas where no culling happened. The experts said this type of culling could not control bTB.

In 2005, early results showed that culling badgers reduced bTB inside the cull area by 19%. However, it increased by 29% in areas just outside the cull zone. This was called a "perturbation effect." Culling changed badger behavior. Surviving badgers moved more widely. This spread the disease to new areas. The report also said culling would cost much more than any benefits. It suggested improving cow control measures instead.

In 2007, the final results were given to the government. The report said "badger culling can make no meaningful contribution to cattle TB control." It suggested focusing on other ways to control bTB.

In 2008, Hilary Benn refused to allow a badger cull. He said it was too hard and costly. He also said it might not work and could make the disease worse. He focused on developing vaccines instead.

What happened after the trials?

A 2010 report looked at bTB after culling ended. It found that the benefits of culling did not last long. They disappeared after three years. The report said culling was unlikely to help control bTB in Britain.

The Bovine TB Eradication Group (2008)

In 2008, a group was set up to fight bTB in England. This group included government officials, vets, and farmers. They looked at research up to 2010. They concluded that culling was not effective.

Our findings show that the reductions in cattle TB incidence achieved by repeated badger culling were not sustained in the long term after culling ended and did not offset the financial costs of culling. These results, combined with evaluation of alternative culling methods, suggest that badger culling is unlikely to contribute effectively to the control of cattle TB in Britain.

After 2010

After the 2010 election, the new Welsh Environment Minister ordered a review. The new Defra Secretary of State, Caroline Spelman, started a bTB program for England. She called it a "science-led cull." The Badger Trust said badgers would be "target practice."

The Badger Trust took the government to court. Their case was dismissed in 2012. The Humane Society International also tried a case, but it failed. Some people think that positive stories about badgers in British books made people oppose culling.

In 2015, culling was expanded to Dorset. It also continued in Gloucestershire and Somerset. By December 2015, Defra said the cull met its targets.

Wales (2009/12)

In 2009, the Welsh Assembly allowed a badger cull. But the Badger Trust challenged this in court. The court stopped the cull. In 2011, the Welsh Assembly chose a five-year vaccination program instead.

The 2012/13 cull (England)

After 2010, culls in England allowed "free shooting" for the first time. This meant shooting badgers that were roaming freely. Before, badgers were trapped in cages and then shot. Farmers could shoot badgers themselves or hire trained people. Farmers paid for the killing. Defra paid for monitoring and data analysis.

What were the goals?

Defra said in 2012 that the goal was to test if controlled shooting was humane. The Badger Trust said the cull had three goals:

- Could 70% of badgers be removed in six weeks?

- Was shooting free-roaming badgers at night humane?

- Was shooting at night safe for people, pets, and farm animals?

None of these goals were about how well culling reduced bTB.

Concerns about free shooting

Allowing free shooting raised concerns. Some worried that wounded badgers might escape underground. This would prevent a second shot to kill them. This means the first shot must kill the badger instantly.

Colin Booty from the RSPCA said badgers are different from foxes. Badgers have thick skulls, skin, and fat. Their bodies are short and squat. Their legs can hide the main killing zone. He said free shooting had a high risk of wounding badgers.

Costs of policing

In 2014, policing the cull in Gloucestershire cost £1.7 million. This was over seven weeks. In Somerset, it cost £739,000.

Government plans

I wish there was some other practical way of dealing with this, but we can’t escape the fact that the evidence supports the case for a controlled reduction of the badger population in areas worst affected by bovine TB. With the problem of TB spreading and no usable vaccine on the horizon, I’m strongly minded to allow controlled culling, carried out by groups of farmers and landowners, as part of a science-led and carefully managed policy of badger control.

In 2011, Caroline Spelman announced the government's plan. A cull would be part of the "Bovine TB Eradication Programme for England." It would start with two pilot areas.

How the cull was carried out

In December 2011, the government said it would go ahead with trials. They would be in two 150 square kilometre areas. The goal was to reduce the badger population by 70% in six weeks. Farmers would pay for the culls. The government would pay for permits and monitoring.

An Independent Panel of Experts (IPE) was appointed in 2012. Their job was to check if the shooting method was effective, humane, and safe. They were not to check if culling reduced bTB in cows. The cull was delayed until 2013.

On August 27, 2013, the culling program began. It was in West Somerset and West Gloucestershire. Up to 5,094 badgers were to be shot. There were times when culling was stopped. This was to protect badgers and their young.

Information collected

Shooters did not reach the 70% target in either area. In Somerset, 850 badgers were killed. In Gloucestershire, 708 were killed. The cull period was extended. In Somerset, 90 more badgers were killed. This made the total 940, a 65% reduction. In Gloucestershire, 213 more badgers were killed. This made the total 921, a 40% reduction.

Defra did not want to share data about the cull methods. But a court decision in 2013 said they were wrong. Defra planned to test 240 badgers for humaneness. But only 120 were tested. Half of these were shot while caged. So, only a small number of free-shot badgers were tested. No badgers were tested for bTB.

Scientists and animal charities asked for more openness. Environment Secretary Owen Paterson said the pilot culls were to see if farmer-led culls could be used in more areas. Farming minister David Heath admitted the cull would not show if shooting was effective or humane. Lord Krebs, who led earlier trials, said the pilots would not give useful information. Owen Paterson famously said, "the badgers moved the goalposts" when explaining why the target was missed.

How effective was the cull?

Defra has said it wishes its policy for controlling TB in cattle to be science-led. There is a substantial body of scientific evidence that indicates that culling badgers will not be an effective or cost-effective policy.

The best informed independent scientific experts agree that culling on a large, long-term, scale will yield modest benefits and that it is likely to make things worse before they get better. It will also make things worse for farmers bordering on the cull areas.

Leaks in 2014 showed that less than half of badgers were killed in both areas. Also, between 6.8% and 18% of badgers took more than five minutes to die. The goal was less than 5%.

Some say that since culling was not selective, many healthy badgers were killed. Experts agree that culling might help a little if done in large areas with clear boundaries. But if badgers can escape, it could make things worse for nearby farms. This is the "perturbation effect."

A Defra report said culling has risks. It could be ineffective or make the disease worse. Vaccination, however, has no similar risks.

The UK government claims a long-term cull could reduce bTB by 9–16%. But many scientists and animal groups disagree. They say culling could wipe out badgers locally. They also say it won't solve the bTB problem in cows. The British Veterinary Association says controlling bTB needs to deal with both cows and wild animals. But John Bourne, a scientist, said that strict cow control alone could reverse the disease. He said cow controls are "totally ineffective" now. He also said the bTB problem starts with cows, not badgers. He believes culling will only make bTB worse by making badgers move around.

The costs of the culls are unclear. They don't include costs like lost tourism. Opponents say the government chose the most inhumane way to fight the disease. Tony Dean from the Gloucestershire Badger Group warned that many badgers would be injured. They would die slowly underground. He also worried that pets might be mistaken for badgers.

Many opponents say vaccinating badgers and cows is better. In Wales, vaccination is used. Stephen James, a farmer, said culling costs £620 per badger. He called it "ridiculous." He said vaccination in clean areas could work better. The Badger Trust also believes vaccination will help. They say vaccination reduces the spread of bacteria from infected badgers.

Dr Robbie McDonald, a lead wildlife scientist for Defra, said culling's benefits are outweighed by its harm to nearby badgers. He said many badgers would need to be killed. It gets harder and more expensive over time.

A Defra study from 2013–2017 showed reduced bTB in farms. It was down 66% in Gloucestershire and 37% in Somerset. But in Dorset, no change was seen after two years of culling.

Proposed 2014/15 cull

In 2014, Owen Paterson decided to continue the culling trials. The Badger Trust challenged this in court. They said he did not use an independent expert panel. Defra said experts from Natural England and the Animal Health Veterinary Laboratory Agency would monitor the cull.

Defra also looked into using carbon monoxide gas in badger setts. The Humane Society International worried about animal suffering from gassing.

The 2014/15 cull (England)

In September 2014, a second year of badger culling began. This was in Gloucestershire and Somerset. The cull was planned to expand to 10 more areas. The Badger Trust said the cull would happen without independent monitoring. Defra denied this.

In 2015, the National Trust, a large landowner, said it would not allow cullers on its land. They wanted to wait for all four years of trial results.

Goals of the 2014/15 cull

The targets for the 2014/15 cull were lower. The goal was still a 70% reduction in badger populations over time. This time, there was more focus on trapping badgers in cages and shooting them at dawn.

Protests against the cull

Like in 2013/14, many protesters entered cull areas. They tried to disrupt the culling. They wanted badgers to stay in their setts or looked for injured badgers. In 2014, police released a trapped badger after protesters pointed out rules.

Dr Brian May, the guitarist from Queen, is against badger culling. He called for the 2014/15 cull to be stopped. He said it was "inept and barbaric." Groups like Team Badger and Gloucestershire Against the Badger Shooting protested the cull.

Policing the cull

In the 2013/2014 cull, police from many areas helped. But in 2014/2015, police focused on local officers. They wanted to deal with local issues.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |