2001 United Kingdom foot-and-mouth outbreak facts for kids

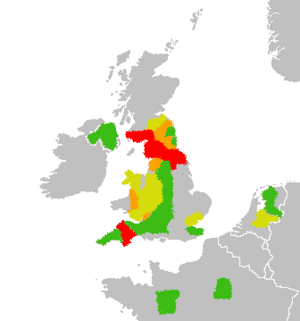

The 2001 foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom was a huge problem for British farms and tourism. This serious animal disease affected 2,000 farms across the country. More than 6 million cows and sheep had to be killed to stop the disease from spreading. Cumbria was the area hit hardest, with 893 cases.

To control the disease, many public walking paths and areas were closed. This made places like the Lake District less popular for tourists. Big events like the Cheltenham Festival and the British Rally Championship were cancelled. Even the general election was delayed by a month. Crufts, a famous dog show, was moved from March to May 2001. By the time the disease was stopped in October 2001, it had cost the UK about £8 billion.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

What Happened Before

Britain's last big outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease was in 1967. That time, it was kept to a small area. After that outbreak, a report said that acting fast was key to stopping future outbreaks. It suggested that sick animals should be killed on the same day they were found and buried quickly.

Later, in 1980, decisions about foot-and-mouth disease moved from the UK government to the European Community (EC). New rules were made, like setting up "protection zones" and "surveillance zones" around infected areas. Also, a rule about protecting groundwater meant that farms couldn't bury animals or use quicklime unless the Environment Agency approved the site.

Farming methods had also changed a lot since 1967. Many local places where animals were killed for meat (called abattoirs) had closed. This meant animals were now moved much longer distances before being slaughtered.

How the Outbreak Started and Spread

First Cases of the Disease

The first case of foot-and-mouth disease was found at a meat processing plant in Little Warley, Essex, on February 19, 2001. It was in pigs that came from Buckinghamshire and the Isle of Wight. Over the next few days, more cases appeared in Essex. The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) quickly stopped animals from moving in and out of areas around the infected farms. On February 21, the European Commission banned the export of all meat, milk, and livestock from the UK.

On February 23, a case was confirmed in Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland. This farm was later found to be where the outbreak began. The owner, Bobby Waugh, was found to have fed his pigs "untreated waste," which is against the rules, and he didn't tell the authorities about the disease. He was banned from keeping farm animals for 15 years.

By February 24, a case was found in Highampton in Devon. Soon after, cases appeared in North Wales. By early March, the disease had reached Cornwall, southern Scotland, and the Lake District, where it spread very quickly.

Even investigators at the Great Heck rail crash in North Yorkshire had to clean their boots and vehicles. This was to prevent the virus from spreading to the crash site's soil.

MAFF decided to "cull" (slaughter) all animals within 3 kilometers (about 2 miles) of known infected farms. At first, this applied only to sheep, not cows or pigs. If dead animals couldn't be buried on the farm, they were taken to a processing plant far away. This meant infected animal bodies were sometimes moved through areas that were still free of the disease.

Stopping the Disease

By March 16, there were 240 cases. Around this time, the Netherlands had a small outbreak. They used vaccinations to stop it, but later, the vaccinated animals were killed to follow EU rules for trade.

Experts like David King and Roy M. Anderson helped MAFF use science to fight the disease. By the end of March, the disease was at its worst, with up to 50 new cases every day.

In April, King announced that the disease was "totally under control." The main way to stop the spread was to kill all animals near an infected farm and then burn them. A complete ban on moving livestock, along with strict rules to stop people from carrying the disease on their clothes and boots, helped control the outbreak during the summer. The culling needed a lot of help. With about 80,000 to 93,000 animals being killed each week, MAFF officials got help from the British Army. From May to September, only about five new cases were reported each day.

The Last Cases

The very last case was reported on Whygill Head Farm in Appleby, Cumbria, on September 30. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), which replaced MAFF, declared the last infected area "high risk" on November 29. The final culling of animals in the UK happened on January 1, 2002, when 2,000 sheep were killed at Donkley Woods Farm, Bellingham, Northumberland. Rules about moving livestock stayed in place into 2002.

With no new positive tests, the UK officially declared itself free of foot-and-mouth disease on January 14, 2002. This ended 11 months of the outbreak.

Effects on Politics

The outbreak caused the local elections in the UK to be delayed by a month. One reason was that bringing many farmers together at polling stations might spread the disease. More importantly, the government had planned to hold the general election on the same day as the local elections. Holding a general election during the crisis was seen as impossible, as government work would slow down during the election campaign. Prime Minister Tony Blair confirmed the delay on April 2. The general election was finally held on June 7, along with the local elections. This was the first time an election had been delayed since the Second World War.

After the election, Tony Blair changed how government departments were organized. Many people felt that the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) had not reacted fast enough to the outbreak. So, MAFF was combined with parts of another department to create the new Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

Foot-and-Mouth in Europe

Several cases of foot-and-mouth disease were reported in Ireland and mainland Europe. This happened because infected animals were unknowingly moved from the UK. People worried about a continent-wide spread, but this didn't happen.

The Netherlands was the country most affected outside the UK, with 25 cases. They used vaccinations to stop the disease. However, the Dutch later killed all vaccinated animals. In the end, between 250,000 and 270,000 cattle were destroyed there.

Ireland had one case in a group of sheep in County Louth in March 2001. Healthy animals around the farm were killed as a precaution. Irish special forces even hunted wild animals like deer that could carry the disease. The outbreak greatly hurt Ireland's food and tourism industries. The 2001 Saint Patrick's Day festival was cancelled and rescheduled for May. Strict safety measures were put in place across Ireland, with most public events cancelled, controls on farm visits, and disinfectant mats at public places.

France had two cases in March. Belgium, Spain, Luxembourg, and Germany also killed some animals as a precaution, but all their tests for the disease were negative. Other European countries put limits on moving livestock from countries that had the disease.

How the Outbreak Was Investigated

Where the Virus Came From

Most experts agree that the foot-and-mouth virus came from infected meat that was fed to pigs at Burnside Farm in Heddon-on-the-Wall. This pig food, called swill, had not been properly heated to kill germs. So, the virus infected the pigs.

Since the virus was not thought to be in the UK before this outbreak, and there were rules against importing meat from countries with foot-and-mouth disease, it's likely the infected meat was brought into the UK illegally. Such imports often go to restaurants and food businesses. A complete ban on feeding catering waste with meat to animals was put in place early in the outbreak.

In June 2004, Defra practiced new procedures for a future outbreak. This was because they found that in 2001, MAFF had not acted fast enough to stop many animals from moving between livestock markets in the UK. Without testing, infected animals were quickly moved, helping the virus spread.

Government Reviews

Because the 2001 outbreak caused as much harm as the previous one in 1967, many people felt that not enough had been learned from the past. So, in August 2001, the government started three reviews to learn from the crisis:

- Inquiry into the lessons to be learned from the foot and mouth disease outbreak of 2001: This review looked at how the government handled the crisis.

- The Royal Society Inquiry into Infectious Diseases in Livestock: This review looked at the science behind the crisis, like how well vaccinations worked and how the virus spread.

- Policy Commission on the Future of Farming and Food: This review focused on how food is produced and delivered in the country in the long term.

All three reviews shared their findings with the public. However, the reviews themselves were held in private. Some farmers and businesses wanted a full public review, but the government said it would be too expensive and take too long. A court agreed with the government.

An Independent Inquiry into Foot and Mouth Disease in Scotland also took place. It looked at the scientific, economic, social, and even emotional effects of the outbreak. It found that the disease cost Scottish farming about £231 million and tourism between £200–250 million. This inquiry suggested that Scotland should have its own lab and focus on developing new testing methods. It also said that emergency vaccination, without killing the animals afterward, should be an option. The importance of keeping farms clean and safe (called biosecurity) was also highlighted.

The Farm Animal Welfare Council, a government advisory group, also published a report with recommendations.

During the outbreak, the government thought about using a vaccine to stop the disease. However, they decided not to, partly because of pressure from the National Farmers Union. Even though the vaccine was thought to work, using it would have stopped British livestock from being exported in the future. This was seen as too big a cost, even though the export industry was small compared to the money lost in tourism. After the outbreak, the law was changed to allow vaccinations instead of just culling animals.

Effects on People's Health and Lives

The Department of Health (DH) supported a research project to study how the 2001 foot-and-mouth outbreak affected people's health and lives. The research focused on Cumbria, the area hit hardest. They collected information through interviews and diaries to understand how the outbreak changed people's lives. In 2008, a book based on this study was published, called Animal Disease and Human Trauma, emotional geographies of disaster.

See also

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |