Bande dessinée facts for kids

Bandes dessinées (pronounced "bahnd dess-ee-NAY"), often shortened to BDs, are comics usually created in French for readers in France and Belgium. These countries have a long history of making comics, different from English-language comics. Belgium is mostly bilingual, so comics originally in Dutch are also part of the BD world.

Some of the most famous BDs include The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé, Spirou and Fantasio by Franquin, Gaston Lagaffe also by Franquin, Asterix by Goscinny and Uderzo, Lucky Luke by Morris and Goscinny, and The Smurfs by Peyo. There are also more realistic BDs like Blueberry and Thorgal.

Contents

Where BDs Are Popular

French is spoken in France, Monaco, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. This shared language helps create a big market for comics. It's why we call them "Franco-Belgian comics."

BDs are also very popular in Quebec, Canada. Quebec has the largest French-speaking population outside Europe. It has strong historical ties to France. European comic publishers like Le Lombard and Dargaud are very active there. This has greatly influenced Quebec's own comics scene since the 1960s. In contrast, English-speaking Canada mostly reads American comics.

Flemish Belgian comics, written in Dutch, have their own distinct style. They are now seen as "Flemish comics." While French BDs are often translated into Dutch, Flemish comics are less often translated into French. This is due to cultural differences.

What Bandes Dessinées Means

The term bandes dessinées literally means "drawn strips." It became popular in the 1960s. The abbreviation "BD" is also used for these comic books, which are often called "albums."

Unlike American "comics" or "funnies," the term bandes dessinées doesn't suggest humor. In French-speaking countries, comics are often called the "ninth art." This idea became popular in the 1960s. It shows how much people respect comics as a serious art form.

In North America, serious Franco-Belgian comics are often called graphic novels. This term has also become popular in Europe. It helps tell the difference between comics for younger readers and those with more adult or complex themes.

A Brief History of BDs

In the 19th century, European artists drew cartoons. They sometimes used multiple panels to tell a story. But they often placed text below the pictures, not in speech bubbles like today. These were usually short, funny works.

Early Days (1900s – 1929)

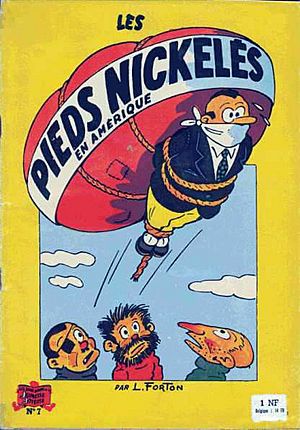

In the early 1900s, comics were found in newspapers and magazines. They were not stand-alone books. Popular French comics from this time include Bécassine and Les Pieds Nickelés.

In the 1920s, French artist Alain Saint-Ogan created Zig et Puce. He was one of the first French artists to use speech bubbles, like in American comics.

Birth of Modern BDs (1929–1940)

One of the first proper Belgian comics was Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin. The story Tintin in the Land of the Soviets appeared in Le Petit Vingtième in 1929. Early Tintin stories were simple. Some had stereotypes that Hergé later regretted.

After Tintin's early success, the magazine started releasing the stories as hardcover books. These were called "comic albums" and used speech bubbles. The 1930 Tintin au pays des Soviets is seen as the very first modern comic album. Tintin became a huge success, translated into many languages. It even inspired a Hollywood movie in 2011.

In 1934, the Journal de Mickey was launched in France. It was a weekly comic book with American series. This magazine was very popular in France and Belgium.

In 1938, the Belgian Spirou magazine began. It was created because Journal de Mickey and Tintin were so popular. Spirou featured American comics at first, but also native ones like Spirou by Rob-Vel and Tif et Tondu by Fernand Dineur. Both series became very popular after the war. Spirou was also published in Dutch as Robbedoes for the Flemish market.

War Years (1940–1944)

When Germany occupied France and Belgium, American comics became hard to get. The Nazis banned American comics they didn't like. This created a chance for young European artists. Many famous Franco-Belgian artists started during this time. They included André Franquin, Peyo, Willy Vandersteen, Jacques Martin, and Albert Uderzo.

Post-War Belgian Dominance (1944–1959)

After the war, some publishers and artists faced accusations of working with the occupiers. Hergé was one of them. He later cleared his name and founded Studio Hergé in 1950. He also started the weekly Tintin magazine in 1946. It became very popular, like Spirou.

Many artists worked for Tintin magazine, including William Vance and Hermann Huppen. The publisher, Le Lombard, was created specifically for Tintin magazine. Le Lombard became one of the three big Belgian comic publishers, along with Dupuis and Casterman.

The success of Spirou and Tintin magazines led to what many call the "golden age" of Belgian comics. American comics became less popular in France and Belgium after the war.

In France, a 1949 law was passed to protect French youth from foreign comics. It also helped French comics compete with popular American ones. This law made it harder for American comics to be published in France. It also affected some Belgian comics. For example, two volumes of the Buck Danny series were banned because they showed a current war. This law led to self-censorship by Belgian publishers to keep their comics in the French market.

France Takes the Lead (1959–1974)

In 1959, the French weekly Pilote magazine launched. It aimed for a teenage audience and quickly became popular with the Asterix series. Many French Catholic magazines lost popularity in the 1960s. This meant Pilote and Vaillant (relaunched as Pif gadget) in France, and Spirou and Tintin in Belgium, gained most of the market.

With publishers like Dargaud (for Pilote), Le Lombard (for Tintin), and Dupuis (for Spirou), the comic market grew strong. French comics became famous across Europe.

France Becomes Preeminent (1974–1990)

After the social changes of May 1968 in France, many new adult comic magazines appeared. Most were French. This showed France becoming the main force in European comics. Magazines like L'Écho des Savanes and Métal Hurlant (which became Heavy Metal in America) were among the first. These publications and their artists are credited with changing Franco-Belgian comics.

Artists gained more creative and financial freedom. They could work as free-lancers instead of being tied to one publisher. This is now the main way artists work.

The new adult magazines changed Pilote magazine. It became a monthly magazine for older teens. But it couldn't regain its top spot because of all the new choices.

Belgium caught up with adult comics when Casterman launched (À Suivre) in 1977. This magazine helped popularize the idea of the graphic novel in Europe. It featured longer, more artistic comics.

French publications and artists continued to lead the field. New French artists debuted in magazines like Fluide Glacial. Publishers like Glénat Editions also became important. They published historical series that showed a more realistic and often harsh view of the past.

Comics as Cultural Heritage

In the 1970s and 1980s, comics gained respect in French society. The French government, especially under Minister of Culture Jack Lang, began to support comics as a real art form. Comics became known as "Le Neuvième Art" ("the 9th art") in France. It's common for adults in France and Belgium to read comics in public. Many comic artists have even received special awards from the government.

Jean Giraud (also known as "Mœbius") is considered one of the most important BD artists after Hergé. He received several special honors from France. His work has been shown in major art museums in Paris. His funeral was attended by the French Minister of Culture.

Belgium also recognizes Franco-Belgian comics as a key part of its culture. The "Belgian Comic Strip Center" opened in Brussels in 1989. It's one of Europe's largest comic museums. Belgium also has smaller museums dedicated to artists like Marc Sleen and Hergé.

In France, a big national comic museum, Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l'image, opened in Angoulême in 2009. Angoulême is also home to France's biggest annual comics festival. One of the museum buildings is named "Le Vaisseau Mœbius" (The Ship Mœbius) after the famous artist.

Recent Times (1990–Present)

The 1990s saw new, smaller independent publishers emerge. These included L'Association and Le Dernier Cri. Their comics, known as "la nouvelle bande dessinée" (new comics), were often more artistic and experimental.

Many famous artists started with these publishers, such as Dupuy and Berberian, Lewis Trondheim, Joann Sfar, and Marjane Satrapi (who created Persepolis).

Comic Formats

Before World War II, comics were mostly in newspapers. Since 1945, the "comic album" format became popular. These are book-like, about half the size of a newspaper. They are usually in color and often have hardcover editions in France. They are larger than American comic books.

The first Tintin albums in the 1930s helped start this format. Albums usually collect stories that first appeared in magazines. They often have 46 or 62 pages.

Jean-Michel Charlier helped make comic albums popular in France. He started a line of albums for Dargaud that collected stories from Pilote magazine. The first Asterix album was a huge success in this format. This led to hardcover albums becoming the norm in France.

Since the mid-1980s, many comics are published directly as albums. They don't appear in magazines first. This is because many comic magazines have closed down. The album format is now common for comics across Europe.

Collected Editions (Intégrales)

Since the 1980s, many popular or classic comic series are released as "omnibus" editions, called intégrales. Each intégrale book usually contains two to four original albums. They often include extra material like unused covers and background information. These editions are popular with adult readers who want to collect their favorite series. They are released in French, Dutch, and other European languages.

Comic Styles

While modern comics mix many styles, there were initially three main styles in Franco-Belgian comics, especially those from Belgium.

Joseph "Jijé" Gilian was a master who worked in all three styles. He learned realistic drawing during World War II when American comics were banned. His realistic style influenced many future artists like Jean Giraud.

Realistic Style

Realistic comics are very detailed. They try to look as convincing and natural as possible, even though they are drawings. They don't use speed lines or exaggerations. The coloring is often subtle. Examples include Jerry Spring by Jijé and Blueberry by Giraud.

Comic-Dynamic Style

This style is lively and energetic, like the work of Franquin and Uderzo. It uses lines of different thickness to make drawings more exciting. Artists working in this style for Spirou magazine, like Franquin, Morris, and Peyo, are often called the "Marcinelle school."

Schematic Style (Ligne Claire)

This style simplifies reality into clear, simple lines. It often lacks shadows and uses geometric shapes and realistic proportions. Drawings are "slow" with few speed lines. It's also known as the "Belgian clean line style" or ligne claire. The Adventures of Tintin is a perfect example and the original model for this style.

After Jijé, French and Italian artists brought in many new art styles from the mid-1970s onwards.

Comics from Other Countries

Franco-Belgian publishers translate many comics from around the world. This includes comics from Italy, Spain, and Argentina. Some German, Swiss, and Polish artists work mainly for Franco-Belgian publishers.

American and British Comics

Traditional American and British superhero comics are less common in the French and Belgian markets. However, graphic novels by artists like Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman are highly respected. Some American comic strips like Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes have been very successful.

In recent years, publishers like Glénat and Delcourt have focused on releasing modern American graphic novels.

Japanese Comics (Manga)

Japanese manga became very popular in France and Belgium from the 1990s onwards. Manga now makes up more than a quarter of all comic sales in France. French comics inspired by manga are called manfra. Publishers have even created special imprints just for manga.

Comic Conventions

There are many comic conventions in Belgium and France. The most famous is the "Angoulême International Comics Festival" in Angoulême, France. It started in 1974 and is held every year. This festival format has been adopted in other European countries.

Conventions feature original art shows, signing sessions with artists, and award ceremonies. The Angoulême festival attracts over 200,000 visitors each year. Unlike American Comic Cons, European comic conventions mostly focus on printed comics.

Claude Moliterni was a key figure in promoting comics as a serious art form in France. He co-founded the Angoulême festival and launched one of the first professional comic journals. His work helped comics become accepted as a mature part of French culture.

Impact and Popularity

Franco-Belgian comics have been translated into most European languages. Some have even become worldwide successes. While many comic magazines have disappeared due to changing reading habits, the number of comic albums sold remains high. Most new comics are now published directly as albums.

The greatest and most lasting success has been for series started in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. These include Lucky Luke, The Smurfs, Asterix, and The Adventures of Tintin. More recent series have not had the same global impact, except in places like the Indian subcontinent.

Notable Comics

Many hundreds of comic series have been made in the Franco-Belgian world. Here are some of the most famous, mostly for young or teenage readers:

- XIII

- Adèle Blanc-Sec

- Alix

- Asterix

- Barbe Rouge

- Bécassine

- Blake and Mortimer

- Blueberry

- Boule and Bill

- Chlorophylle

- Cubitus

- Les Cités Obscures

- Gaston

- Incal

- Iznogoud

- Jerry Spring

- Jommeke

- Kiekeboe

- Largo Winch

- Luc Orient

- Lucky Luke

- Marsupilami

- Michel Vaillant

- Nero

- Rahan

- Ric Hochet

- The Smurfs

- Spike and Suzy

- Spirou et Fantasio

- Thorgal

- The Adventures of Tintin

- Titeuf

- Les Tuniques Bleues

- Valérian and Laureline

- Yoko Tsuno

- Zig et Puce

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historieta franco-belga para niños

In Spanish: Historieta franco-belga para niños