Bartolomeo Cristofori facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bartolomeo Cristofori

|

|

|---|---|

Photo of a 1726 portrait of Bartolomeo Cristofori. The original was lost in the Second World War.

|

|

| Born |

Bartolomeo Cristofori di Francesco

May 4, 1655 |

| Died | January 27, 1731 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Inventor, instrument maker |

| Known for | Inventor of the piano |

Bartolomeo Cristofori di Francesco (born May 4, 1655 – died January 27, 1731) was an Italian musical instrument maker. He is famous for inventing the piano.

Contents

Life of Bartolomeo Cristofori

Bartolomeo Cristofori was born in Padua, which was part of the Republic of Venice at the time. We don't know much about his early life. Some people thought he trained with the famous violin maker Nicolò Amati. However, records show this was likely not true.

Working for the Medici Family

The most important event in Cristofori's early life happened in 1688. At 33 years old, he was hired by Prince Ferdinando de' Medici. Ferdinando was the son of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. He loved music and collected many musical instruments.

It's not fully clear why Ferdinando chose Cristofori. The Prince might have met him during a trip. Ferdinando needed someone to take care of his instruments. But it seems he also wanted Cristofori for his inventing skills. Cristofori was likely already known for being creative.

Cristofori agreed to the job. He moved to Florence in May 1688. The Grand Duke's government gave him a house and tools. His job was to tune, maintain, and move instruments. He also worked on his own inventions and repaired old harpsichords. Cristofori eventually got his own workshop. He usually had one or two assistants helping him.

Cristofori's Early Inventions

Before inventing the piano, Cristofori created two other keyboard instruments. These were listed in an inventory from 1700, which recorded Prince Ferdinando's instrument collection.

One invention was the spinettone. This was a large spinet, which is a type of harpsichord. It had more strings than a usual spinet, making it louder. It might have been used in crowded orchestra pits for plays.

His other invention, from 1690, was the oval spinet. This was a unique type of virginal. Its longest strings were in the middle of the instrument's case.

Cristofori also built regular instruments. These included a clavicytherium (an upright harpsichord) and two standard harpsichords. One of these harpsichords had an unusual case made of ebony.

The Invention of the Piano

The first clear mention of the piano is from the 1700 Medici inventory. The entry for Cristofori's new instrument said:

- An "Arpicembalo" by Bartolomeo Cristofori, of new invention that produces soft and loud, with two sets of strings at unison pitch, with soundboard of cypress without rose...

The name "Arpicembalo" meant "harp-harpsichord." But the important part was "che fa' il piano, e il forte", meaning "that makes soft and loud." Over time, this phrase was shortened to "piano."

This first piano, which is now lost, had a range of four octaves. This was a common size for harpsichords.

By 1711, Cristofori had built three pianos. The Medici family gave one to a important church leader in Rome. Two others were sold in Florence.

Later Years and Legacy

Prince Ferdinando, Cristofori's boss, died in 1713. Cristofori continued to work for the Medici court. In 1716, he was given the title of "custodian" of the instrument collection.

As the Medici family's wealth decreased, Cristofori began selling his instruments to other buyers. The King of Portugal bought at least one of his pianos.

In 1726, a portrait of Cristofori was painted. It showed him proudly standing next to what looks like a piano. He held a paper, possibly a diagram of his piano's inner workings. This portrait was destroyed during World War II, but photos of it still exist.

Cristofori kept making pianos and improving them until he was very old. He was helped by Giovanni Ferrini, who later became a famous instrument maker himself. Another assistant, P. Domenico Dal Mela, might have built the first upright piano in 1739.

Bartolomeo Cristofori died on January 27, 1731, at the age of 75.

Cristofori's Pianos Today

We don't know how many pianos Cristofori built in total. Only three of his pianos still exist today. All of them were made in the 1720s.

- A 1720 piano is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It has been changed a lot over time.

- A 1722 piano is in the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome. It has a four-octave range and a special "una corda" (one string) pedal. This piano is damaged and cannot be played.

- A 1726 piano is in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum in Leipzig. It also has a four-octave range and an "una corda" pedal. This instrument cannot be played now, but recordings were made in the past.

All three surviving pianos have the same Latin message on them. It says: "Bartolomeo Cristofori of Padua, inventor, made [this] in Florence in [date]."

How Cristofori Designed His Pianos

Cristofori's pianos from the 1720s had most of the important features of modern pianos. They were built very lightly and did not have a metal frame. This meant they couldn't make a very loud sound. Metal frames were added to pianos around 1820 to make them louder.

The Piano Action

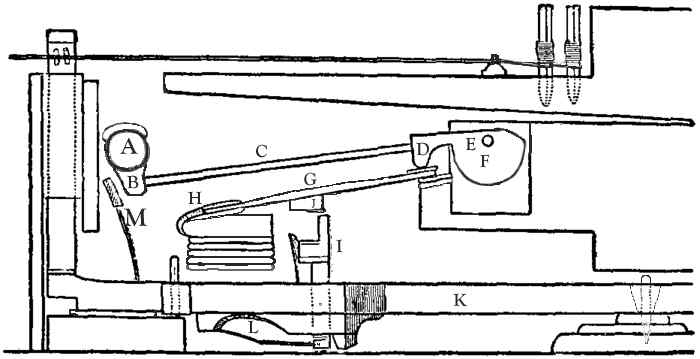

The "action" of a piano is the complex system that connects the keys to the hammers. Cristofori's action was very clever.

1. When you press a key, it doesn't lift the hammer all the way to the string. If it did, the hammer would block the string's sound. 2. Cristofori's design used a special part called a 'hopper' (I in the diagram). This hopper lets go of the hammer (C) just before it hits the string. This way, the hammer strikes the string and then falls back quickly. 3. The action also made the hammer's movement much bigger than the finger's movement. This helped to make the sound louder. 4. To prevent the hammer from bouncing and hitting the string twice, Cristofori added a 'check' (M). This part catches the hammer after it hits the string. It holds the hammer until the player lifts their finger.

Cristofori's action was complex to build. But its basic ideas are still used in modern pianos today.

Hammers

The hammers in Cristofori's pianos (A in the diagram) were made of paper. They were rolled into a coil and glued. A strip of leather was added where the hammer hit the string. This leather made the sound softer.

Just like modern pianos, the hammers were bigger for the low notes. They were smaller for the high notes.

Frame

Cristofori's pianos had an inner frame that supported the soundboard. This frame was separate from the outer case. This design meant the soundboard wasn't squeezed by the string tension. This helped the sound and prevented the wood from warping.

Modern pianos still use this idea. Their strong iron frames hold the huge tension of the strings.

Tuning Pins

On some of his pianos, Cristofori placed the tuning pins in an unusual way. The pins went all the way through the wood they were in. You tuned the piano from the top, but the strings wrapped around the pins on the bottom.

This made it harder to change broken strings. But it had benefits. The hammers hit the strings from below. This pushed the strings firmly into place. This design also allowed for smaller, lighter hammers. This made the piano easier to play.

Soundboard

Cristofori used cypress wood for his soundboards. This wood was traditionally used for harpsichords in Italy. Today, spruce wood is usually used for piano soundboards.

Strings

Cristofori's pianos had two strings for each note. Modern pianos often have three strings for higher notes.

Some of his pianos had an early version of the soft pedal. The player could slide the entire action a little bit. This made the hammers hit only one of the two strings. This created a softer sound, like the "una corda" pedal on modern pianos.

It's hard to know exactly what metal Cristofori's original strings were made of. Strings break and are replaced over time. Records suggest he used iron wire for most notes and brass for the bass notes.

What Cristofori's Pianos Sounded Like

It's difficult to know the exact sound of Cristofori's original pianos. The surviving instruments are either too old to play or have been changed a lot.

However, many modern builders have made copies of Cristofori's pianos. These copies help us understand their sound. The sound of these replica pianos is somewhere between a harpsichord and a modern piano. The notes don't start as sharply as on a harpsichord. And you can clearly hear the difference when the player changes how they touch the keys.

Other Surviving Instruments by Cristofori

Besides the three pianos, nine other instruments made by Cristofori still exist today.

- Two oval spinets, from 1690 and 1693. One is in Florence, and the other is in Leipzig.

- A spinettone, also in the Leipzig museum.

- An early harpsichord from the 17th century, with an ebony case. It's in Florence.

- Two harpsichords from 1722 and 1726, both in the Leipzig museum. The 1726 harpsichord is special because it has a "two-foot" stop, which is rare for Italian harpsichords.

Some of these later instruments might have been partly built by his assistant, Giovanni Ferrini.

How People Remember Cristofori

During his lifetime, Cristofori was highly respected for inventing the piano. When he died, a musician at the Medici court wrote in his diary:

- 1731, January 27, Bartolomeo Cristofori, called Bartolo Padovano, died. He was a famous instrument maker for Prince Ferdinando and a skilled maker of keyboard instruments. He was also the inventor of the pianoforte, which is known throughout Europe. He even served the King of Portugal, who paid a lot of money for his instruments. He died at the age of seventy-five years.

After his death, Cristofori's fame faded for a while. For a time, people in France thought the piano was invented by a German builder named Gottfried Silbermann. But Silbermann's pianos actually used Cristofori's hammer action design. Later studies corrected this mistake.

In recent times, people have studied Cristofori's instruments carefully. Experts today greatly admire his work. The New Grove encyclopedia calls his work "tremendous ingenuity." One scholar, Grant O'Brien, even compared Cristofori's genius to that of the famous violin maker Antonio Stradivari.

Cristofori is praised for his originality in inventing the piano. While there were some earlier attempts at piano-like instruments, it's not clear if Cristofori even knew about them. The piano is a rare example where a major invention can be clearly linked to one person. And that person brought it to a high level of perfection all by himself.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bartolomeo Cristofori para niños

In Spanish: Bartolomeo Cristofori para niños