Bathsua Makin facts for kids

Bathsua Reginald Makin (born around 1600 – died around 1675) was an important teacher in 17th-century England. She spoke out about how women were treated at home and in public life. Bathsua Makin was very well-educated. People called her England's most learned lady. She knew many languages, including Greek, Latin, Hebrew, German, Spanish, French, and Italian.

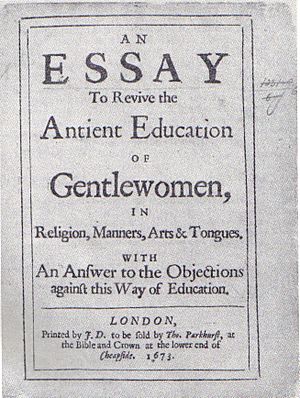

Makin strongly believed that women and girls should have the same right to get an education as men. This was a time when many people thought women were weaker and could not be educated. She is most famous for her book, An Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen (1673). In this book, she argued for better education for women.

Contents

Life of Bathsua Makin

Bathsua Makin was born in 1600. She was named after the biblical Bathsheba. Her father, Henry Reginald, was a schoolmaster in Stepney. He also wrote poems in Latin and books about math tools. In 1616, when she was only 16, Bathsua published her own book called Musa Virginea. It had poems in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, French, and German. The book said she was "Bathsua Reginald, daughter of Henry Reginald, a schoolmaster and language expert from London."

In 1621, she married Richard Makin, who worked for the king. They moved to Westminster and had eight children.

Her sister, Ithamaria, married the mathematician John Pell in 1632. Bathsua Makin wrote letters to Pell. These letters show they were close, and she signed them "your loving sister."

Working as a Teacher

By 1640, Bathsua Makin was known as the smartest woman in England. She taught the children of Charles I of England, the King. She was also the governess (a private teacher) for his daughter, Princess Elizabeth Stuart.

When the English Parliament took Princess Elizabeth Stuart during the English Civil War, Makin stayed with the princess as her helper. Princess Elizabeth died in 1650. Makin was supposed to get money for her work, but she never received it.

Makin also taught Lady Elizabeth Langham. Lady Elizabeth was the daughter of a powerful family. Bathsua likely taught her until Lady Elizabeth got married in 1652.

During the civil war, Bathsua's husband was away. She raised their children by herself. He died in 1659. Her sister died two years later.

Makin's School

By 1673, Bathsua Makin and Mark Lewis opened a school for young ladies. It was in Tottenham High Cross, which was a few miles outside London. Famous women like Elizabeth Drake and Sarah Scott are said to have gone to this school.

The school taught many subjects. Students learned music, singing, and dancing. They also learned to write in English and how to manage money. For those who wanted to learn more, the school offered Latin and French. Students could even learn Greek, Hebrew, Italian, and Spanish.

In 1673, Makin shared a booklet called "An Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen." This booklet strongly argued for educating women.

Bathsua Makin's Writings

Who Influenced Her Ideas

Bathsua Makin wrote letters to Anna Maria van Schurman, a famous Dutch scholar. Schurman even mentioned Makin in one of her own letters. This letter was published in 1659 with an English translation of Schurman's book about women's education.

Makin also praised Schurman in her book, An Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen. Both Makin and van Schurman believed that only women with enough time, money, and intelligence should get a good education.

Mary Astell later used similar ideas in her book "A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Part I" in 1694. Makin looked to powerful women like Queen Elizabeth I to support her arguments. Queen Elizabeth I had received an excellent education when she was young. Makin also mentioned Margaret Roper and Anne Cooke Bacon. She said that educating women would help the country. Makin even argued that the "Reformation of Religion" (a big change in the church) was started and continued by women.

Makin was also inspired by John Amos Comenius. She followed his advice that teachers should use everyday language instead of Latin when teaching.

Her Famous Book: An Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen

Makin's book is divided into three parts. It starts with a letter that supports educating women. Then, there's a letter that argues against it. The longest part is the third section. It defends women's right to speak and explains why women should be educated. The book was dedicated to Lady Mary, who was the oldest daughter of the Duke of York (who later became King James II).

In the third part of the book, Makin briefly talks about the history of women's education. She names women who were very successful, like Aspasia and Margaret Cavendish. Makin knew that women had little money or political power. So, she argued they needed to gain power through their words and ideas.

She said that if women were in charge of a household (which often happened during the English Civil War), they needed to "understand, read, write, and speak their Mother Tongue." Makin believed that because women usually didn't speak in public, they needed to learn how to talk well. This would help them in conversations with their husbands and in doing their household duties.

Bathsua Makin's Legacy

Bathsua Makin is sometimes called a "proto-feminist". This means she had ideas that were similar to early feminists, even before the feminist movement began. However, like Christine de Pizan before her, Makin came from a family that valued learning. She argued for women to be equal in their intelligence and education, not necessarily in politics.

In her book, Makin wrote, "Let not your Ladiships be offended that I do not (as some have wittily done) plead for Female Preeminence. To ask too much is the way to be denied all." This shows she was careful not to ask for too much, so her ideas about education would be accepted. Even so, her arguments for educating women helped pave the way for the first feminists.

Works

- You can read an online version of Bathsua Makin's An Essay To Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen, in Religion, Manners, Arts & Tongues, With An Answer to the Objections against this Way of Education at A Celebration of Women Writers.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |